On 28 June 2020, as Benjamin Netanyahu pressed forward with annexation plans to further dispossess Palestinians of their land and rights, Black Lives Matter (BLM) UK reeled off a series of tweets in solidarity with the ongoing Palestinian struggle for liberation. Some popular black Twitter commenters who had previously been enthused by the resurgence of BLMUK were vocal in their disdain.

BLM, they argued, is a movement specifically about black lives; therefore, to stand in solidarity with Palestinians is to hijack the movement with a distraction. In the weeks before, there had been a concerted effort, led by the Daily Mail, to smear BLMUK activists such as Joshua Virasami as subversive Marxists who sought to use the movement as cover to ‘abolish the police, smash capitalism and … close all prisons’. These claims didn’t seem to dissuade a newly radicalised generation of black voices, which speaks to broadened black political horizons since 2014.

It seems apt, then, to interrogate why Palestine – a cause long entangled with the political imaginaries of those seeking universalist emancipatory projects – revealed a deep and acrimonious fault line in black politics. It’s important to note that this was not the first ‘Palestine scandal’ in relation to BLM. As the US city of Ferguson, Missouri, exploded over the murder of Mike Brown in 2014, Palestinians besieged in Gaza sent not only solidarity but also advice for activists on how to handle the violent tactics of the state, such as teargassing, which they knew all too well.

In 2015, a delegation of representatives from Ferguson, Black Lives Matter and the Black Youth Project took a historic trip to Palestine led by the Dream Defenders, in which they deepened their understanding of the relationship between black and Palestinian struggles. Upon their return, they released a joint statement of solidarity. The fallout was far-reaching. BLM co-founder Patrisse Cullors explained that many funders pulled out; black lives in America was one thing but Palestinian lives were something entirely different.

Becoming black

To understand the affinity between black struggle and Palestine, we must trace back to the moment in the 20th century when ‘negroes’ became ‘black’. Blackness as a generalised form of self-identification is a relatively new phenomenon in the west and, at the genesis of its widespread adoption, it was an explicitly political one. In 1966, as he emerged from the jail cell where he’d been held for his voter registration agitation, Stokely Carmichael’s first words were ‘Black power!’ That phrase invoked a radically new era of black political organisation, marked by a fundamental shift in the political imagination, from the negro to the black.

The ‘negro question’ had held the mirror up to US society, challenging its morality for sending people to Vietnam to fight for freedoms to which they were not entitled at home. The ‘black question’ did something more dramatic: it posited a common identity between some Americans and the Vietnamese people, the wretched of the earth. In America, that meant asking why war was being waged on the Vietnamese, charting a path which refused to be placated by a cut of the bloody spoils.

To the black political imaginary, emancipation predicated on the domination of others was no emancipation at all. The identification of black Americans as black was not a natural process – it was a reaction to and disruption of a negro politics that saw the political horizons of negroes within the confines of the US state. This shift was therefore not simply a semantic one. It marked a rejection of the domestic blinkers that shackled the civil rights political establishment. Carmichael’s speech is often misunderstood as a call to get black power.

Instead it was a call to unlock a black power already latent in America. To him, blackness was a structural position brought into being by material conditions, rather than any innate quality of particular people. A position created by American society, which then made possible the radical critique of that society. ‘We must question the values of this society,’ Carmichael asserted. ‘Black people are the best people to do that because we have been excluded from that society and the question is… whether or not we want to become a part of that society.’

To the black political imaginary, emancipation predicated on the domination of others was no emancipation at all

The material position of American ‘negroes’ created a vantage point and a language for blackness: a section excluded from US society but fundamentally embroiled in it, who were able to ask existential questions about the role of America as an imperial power. Rather than an assemblage of cultural markers, as it is now usually imagined, blackness was a structural position that provided the tools for critique of America’s rise as a global power. It is not surprising, then, that the ‘revolutionary culture’ was a central theme – to which extensive essays, speeches and art were dedicated.

‘A revolutionary culture is the only valid culture for the oppressed!’ This language of blackness spread across the globe as black people within the metropole began to define their structural relation to empire as a focal point for organising. From the multi-racial British Black Panther Party, to the black consciousness movement in South Africa (which saw blackness as a state of mind inclusive of the country’s Asian populations), this conception of blackness was globalised. The conditions of interconnectivity – a global system of wealth extraction with shared apparatuses of repression and domination – meant not that all groups fighting against imperialism were the same but that the destinies of their liberation struggles were fundamentally linked.

This point, made by Frantz Fanon, Huey Newton and countless other militants, was given expression in new transnational alliances. As this changing language took shape, there was a concurrent shift in political sympathies within the black movement. Earlier sympathies with the Zionist project gave way to conceptual and material connections between the black power movement and the Palestinian revolution. Fuelled by the international solidarity that poured out of countries and movements fighting US imperialism, from Algeria to Vietnam, organisations such as the Black Panther Party and the Student Non-Violent Co-ordinating Committee began sending delegations to the Tricontinental, a conference of revolutionary movements from Africa, Asia and Latin America.

Catalysed by what they were learning from revolutionaries around the world – and from the 1967 war, which rocketed the Palestinians to the forefront of American politics – many black radicals picked up the threads laid by Malcolm X’s commitment to the Palestinian cause. This commitment was embraced by the Tricontinental as black Americans embedded themselves in the international networks of solidarity that co-ordinated and sustained anti-imperialist struggles across the third world. From Palestinians, the Black Panther Party learnt military and political strategies of resistance detailed in memoirs from former Panthers, such as Flores Forbes’ Will You Die with Me?

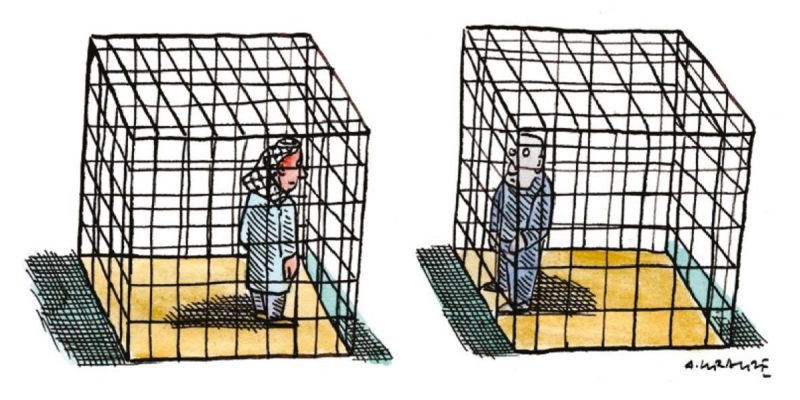

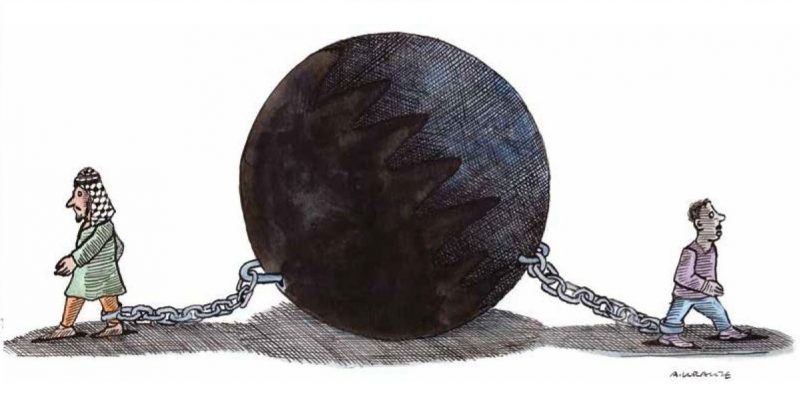

CREDIT: ANDRZEJ KRAUZE

Becoming hyphenated

In the late 1980s, the Reverend Jesse Jackson was leading the charge in calling for blackness to be ditched and replaced with ‘African American’. It became a defining transition in black American history. Two arguments were made for this shift. First, the claim that blackness had represented a sense of shame in and a refusal to engage with the African heritage of America’s black population. This might seem strange, given that black power was originally articulated by sections of the black movement who saw themselves as black nationalists and wanted to reconnect themselves with ongoing struggles for liberation on the African continent.

Second, tellingly, was the argument that black held more negative associations in people’s minds – African American sounded less threatening. While the debate was inconclusive, African American steadily replaced black in textbooks and state ethnic data gathering. African American held the respectability of other hyphenated groups that had included themselves in the American family, such as Italian Americans and Asian Americans. The black was once again an American, the descendant of slaves, and black freedom was once again contained within the nation’s borders.

This transition was not only happening in America. Across the global north, black was either given suffixes tying diasporic populations to the metropole or ditched altogether. In Britain, the 1991 census was the first to include an ethnic designation beyond ‘white’ or ‘coloured’. Black – a category which had once encompassed all former subjects of empire – was co-opted by the state and became: ‘Black African’, ‘Black Caribbean’, ‘Indian’, ‘Pakistani’, ‘Bangladeshi’. Those of mixed heritage had to choose. This data failed, and continues to fail, to distinguish ‘race’ (as a constructed and real social hierarchy) from ‘ethnicity’ and geographical heritage, but that is not what it was intended to do.

In the administration of empire, ethnicity data gathering did the work of creating ethnicities by making these ‘communities’ a primary mode through which the citizen and non-citizen alike navigated their relationship with the state – the groups have not been static, but they remain defined by the state. The classifications were not neutral but formed the datasets for investigations into racial inequality – determining the language through which communities could seek funding and redress for harms from the state. In Britain, as in America, narrower, discrete categories became naturalised as the contours of race. Anti-racism was largely shorn of its internationalism as political horizons retreated into ‘community organising’.

Becoming bourgeois

Throughout this process, the material conditions sustaining any coherent black community with a single collective interest were also eroded. We saw the emergence and consolidation of a black bourgeoisie whose daily lives did not reflect the conditions of domination embedded in earlier accounts of blackness. Instead, the husk of this relation was transformed into a cultural politics in which blackness existed as an abstract community that obfuscates rather than illuminates the conditions it emerged to articulate. Many within this emergent black bourgeoisie have clung to blackness to position themselves as dominated while appropriating the trauma of working-class black communities who live the conditions of domination, exploitation and carcerality that previously tied black struggle to the internationalist politics of the global south, not least Palestine.

This contradiction was displaced into anxieties about the exploitation of black people by non-black people of colour. You could now speak of black wealth as collective, shared in some abstract sense by the working-class black people from whose exploitation it was amassed. The task was no longer to dismantle the oppressive structure of race, and the extractive processes that create and sustain it but rather to manage the essentially oppositional interests of different communities of colour. The black militant has been largely replaced in the popular imaginary by the black columnist. In such a world, the question of Palestine has become a black political litmus test.

As Angela Davis continues to argue passionately, solidarity with Palestinians comes from more than a place of sympathy. It involves a recognition of the shared history of struggle and the similarities linking the technologies of domination levelled against us. ‘Palestine under Israeli occupation is the worst possible example of a carceral society,’ Davis says. This framing sees blackness as political, one relation within a broader matrix of imperialist domination. It sees black struggle as one contour of a politics that also encapsulates Palestinian struggle and every other struggle against imperialism – ‘a world struggle’. By contrast, the ethnic black frame rejects the possibility of such a common cause. It posits comparisons with Palestine as essentially antiblack, thus paralysing routes to solidarity.

Recovering agency

Black politics faces fundamental challenges today; 1970s slogans ring hollow now. The apparatuses of domination to which they refer have evolved in response to our gains. Recounting these bitter transformations of racial politics is not a call for imitating the language and imagery of old; it is instead to render explicit the logics and conditions that shaped the thinking that today presents itself to us as natural. Identities transform, they do not inscribe themselves on blank canvases – words accumulate layers of meaning in their travels like old library books annotated by generation after generation. I like the metaphor of the palimpsest: blackness in its new form will always bear the weight of the morphology that clouds its history.

If the great mystification of racecraft inheres in presenting recent historical constructions as if they were natural and eternal, then the work of demystification means recovering agency: expanding the range of things in our lives we believe we can change. How we identify ourselves, and with whom we find common cause are two of those things – we just need to find a language to express it. The words of righteous indignation might retain their force over time (racism, after all, is still with us) but what really matters is to ask afresh what winning would look like in changed conditions.