The Covid-19 pandemic has turned the world upside down, forcing many changes at work. One of the most regularly discussed has been the shift to remote working. For many workers who have long been arguing for it, suddenly it has become possible to work without the commute to the office. However, this experiment has highlighted the darker side to remote working: surveillance at work. For example, demand for ‘employee surveillance software’ has jumped by 58 per cent since the start of the pandemic.

Crises of any cause have always presented opportunities for changes to be forced through. As the current crisis continues to unfold, it is therefore necessary to understand what is happening with workplace surveillance – and more importantly, how we can fight it.

Histories of surveillance

There is a long history of being watched at work. Whether we call it supervision, management or surveillance, bosses have always been keen to know what workers are up to. This involves watching to make sure they are putting in the effort and commitment that bosses require of them, particularly when trying to get them to work harder. It is part of the control that bosses attempt to exercise once we have agreed to work for them.

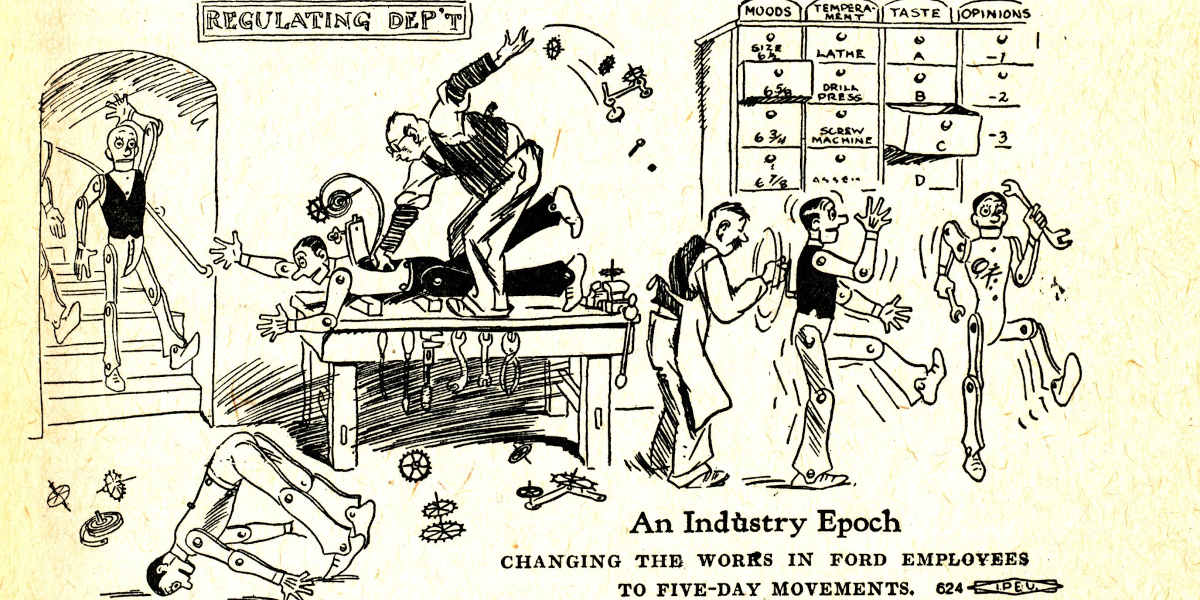

In 1911, Frederick W Taylor, the so-called father of modern management theory, put forward a clear argument for supervision at work. He believed that workers would always try to put in less effort. ‘Underworking’, so he argued, involved ‘deliberately working slowly so as to avoid doing a full day’s work’, also known as ‘soldiering’, and ‘constitutes the greatest evil with which the working-people … are now afflicted’. Along with its connection to slavery and racism, Taylorism developed a supposedly ‘scientific’ approach to management based on the breaking down of work into quantifiable tasks. Surveillance here was achieved with the stopwatch, with the aim of exerting control over all aspects of the work, preventing the worker from soldiering.

We can trace the development of Taylorism across different kinds of work. Taylor was writing about the management of factories. Some of the ideas were implemented in assembly lines, which take control away from the individual worker by centrally setting the pace. Supervisors conduct physical surveillance on the factory floor.

The call centre represented an important step forward in the technologies of surveillance at work. The combination of computers and telephones allows for software to be easily used to monitor the performance of call centre workers. The computational control also allows for speeding up the rate of calls, creating ‘an assembly line in the head’ of workers. Data is generated automatically about worker performance, calculating the length of calls, success rates, sales and so on.

The lessons of call centres have been applied in platform work and the gig economy, with companies such as Deliveroo and Uber. Here we can see ‘algorithmic management’ that takes the automation of surveillance further by providing algorithmic decision making – often taking the form of so-called ‘deactivations’ in which workers are fired. This represents another attempt at exerting control over work, but the practical application of tools like these is always more complicated. Across all these examples, workers find ways to circumvent or subvert technologies. However, these automated methods of surveillance have proven successful across different platforms, and they are increasingly being applied elsewhere.

Making sense of surveillance

While these examples show us the histories behind the software now being implemented at work, it is important to note the difference between surveillance and control. Surveillance involves capturing information or generating data about work. While this can be disconcerting, the data alone does not have any power. It is through processes of control that the information and data is turned into something that can be actioned by bosses – for example, taking the measurements of factory work and requiring workers to speed up, or setting targets for deliveries with the threat of deactivation.

The Covid-19 pandemic has presented a unique opportunity for bosses to apply new forms of surveillance and control. However, it is worth noting that the ‘great work from home experiment’ was not something that all workers got to take part in. While many office workers were able to work from home, many other workers stayed on site as security or cleaners. Many ‘key workers’ across different sectors, such as healthcare, did not get to work from home; nor did the many gig workers delivering food to the new working-from-home population.

Automated methods of surveillance have proven successful across different platforms, and they are increasingly being applied elsewhere

For workers who did start working from home, you can easily imagine that the fear of ‘soldiering’ has increased for bosses. This no longer meant slow work in the workplace, but long lie-ins, extended lunches, and videogames and Netflix instead of emails. Bosses are no longer able to have supervisors physically check up on workers, so a range of existing surveillance tools have found a much wider use.

There are many companies now selling ‘employee surveillance software’ or other similar kinds of tools. As UTAW (the United Tech and Allied Workers) explain in their recent report on the topic, this can include tools to read instant messages and emails; application usage recording; viewing calendars, notes and reminders; remote desktop control; monitoring internet activity; keylogging and mouse tracking; GPS and mobile device tracking; and recording and screenshotting employees’ screens. Such activities intrude deeply into working lives and greatly undermine privacy. There is also a risk that these can continue beyond working hours.

To give you a sense of what these companies offer, take StaffCop, for example. Their employment monitoring solution claims to ‘identify the laggards or high performers with active vs idle time analysis and create a continuous feedback loop to refine and adjust your organisational workflow’. It would not take much to guess the purpose of Kickidler’s tools, particularly given the logo depicts the ‘k’ kicking the ‘idler’.

How do we fight surveillance?

Most workers have very little say over decisions that are made about their work. The changes brought about

during the pandemic often happened with very little consultation, pushed by the threat of Covid-19. It is worth remembering that huge numbers of people have died – and are dying – many of them from infection at work. Many workers have juggled sickness, childcare, bereavement and more while adjusting to remote work. Yet somehow many bosses are concerned that there might be some idle time during the working day.

Technology is often presented to us as a solution, a step forward, or something that could only improve things. However, technologies are designed, made and used within existing relationships in society. For example, take the technologies of surveillance and control developed in call centres. The choices to monitor quantitative targets, how to collect the data and how that data is then used by managers are all driven by the relationships already present in the call centre. It is not the surveillance software that is the cause of the problems for many workers, but how they are treated by management.

Clearly, there are few – if any – of us who would choose to be under surveillance while working, whether in a workplace or from home. The introduction of these new technologies should require the consent and consultation of workers, rather than a unilateral decision by bosses. However, as most workplaces today do not have strong collective organisation or effective bargaining, bosses have an opportunity with the Covid-19 pandemic to take even more control.

This makes fighting surveillance at work challenging. The first step is to be able to recognise these new tools when they are being introduced. If you are concerned that your employer might be using them, the UTAW report provides an accessible guide to ‘spotting surveillance software’ and lists the most popular providers. Sharing information about what tools are being used is an important step in understanding when and how we need to fight.

The second step is finding a way to say ‘no’ to these tools. In a workplace with collective organisation and trade unions this means talking to co-workers, calling a meeting and planning action. Cleaners and porters at UCL’s Institute of Education did something similar when the outsourcing company, Sodexo, announced it would introduce a new time management system with biometric fingerprinting for clocking in. They refused to comply and disrupted the implementation, leading to its withdrawal.

In many workplaces saying ‘no’ can feel like a much bigger task. The first part of doing this is recognising that these technologies are not neutral and that it is legitimate for workers to refuse changes that they do not agree with. The next part is finding a way to build the collective power necessary to do so. This means talking to co-workers, joining a union, and sharing what is happening.

The growing use of surveillance software clearly shows how bosses want to transform work after the pandemic through increased control. Now is the time for workers to organise against this. Fighting it starts by saying ‘no’.