I started painting as a teenager. I went to art school at 16. After being on demonstrations against the war in Vietnam, I saw how the police acted. With the civil rights movement in the States, there was a sense of protests going on all over the world. I wanted to find a visual language to bring these together.

Paint seemed too slow to me. So I started using photography to record demonstrations, merging photographs – my own and others’ – to represent state forces in relation to people’s actions, taking apart the reality constructed by the media.

Vietnam was highly photographed and the images had a big effect on anti-war movements. I wanted my work to become part of an anti-war movement rather than something separate in the art world. I started doing work for left newspapers.

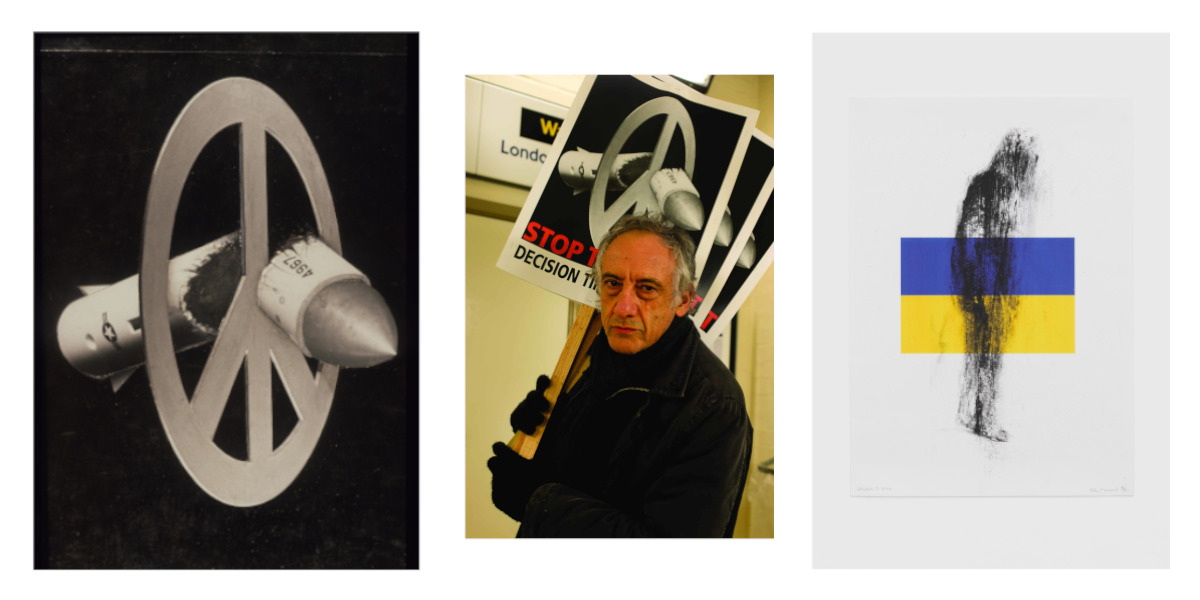

I started creating images for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) in the late 1970s, when Thatcher was bringing American cruise missiles to Greenham Common and Molesworth. People were still using images of nuclear clouds – nuclear weapons were part of the culture for years. Now with Ukraine, people have realised they still exist and are more and more horrific in their technology.

One of the purposes of my work has always been to activate people. I’ve had letters saying, ‘I saw your work and I got involved in the peace movement, in Amnesty or CND.’ I’ve seen people’s versions of my ‘broken missile’ image (above) – for example, in papier-mâché. That’s always cool, even though it’s depressing that it’s still as relevant 40 years on.

I began working in galleries. For CND, I’d have to make images that people would get very quickly, whereas in a gallery there can be more subtlety in the imagery. People have to disentangle it. They relate to it differently. I love working in that way.

I don’t have any place I won’t show my work. I showed at the Imperial War Museum, with all the technology on show. But it was great because young people saw my exhibition. I started giving workshops there, sometimes over 100 kids making work about their own lives in relation to war, through looking at my stuff. The art world doesn’t want anything too loaded politically. Teaching has given me the freedom to do what I want, even though it’s not selling.

I’ve also given workshops in schools and colleges, with kids that haven’t been to school, and with older people. Once you have material laid out, and a scanner and printer, people suddenly realise they can relate to it through their own image-making. I never tell them to do anything in particular. They might put a family photo next to some advert for a fast car, and that relationship can start a discussion about the society we’re living in.

My students at the Royal College of Art are very concerned with making socio-political art, especially around climate change. The government wants to cut funding from art because they know it can radicalise young people, open things up to them rather than putting them into a box.

With the current situation, I could despair and say everything I’ve done in 50 years is useless – but it’s a slow consciousness-raising. You can’t measure the impact of art.