In July 2022, a courtroom fell into shared grief as the fate of ten black boys was read out by a judge at Preston Crown Court. This case, which I will refer to as the Manchester 10, would see a collective punishment of 131 years handed down across the group: a group labelled a ‘gang’ by the police and prosecution. Prior to sentencing, four of the boys were found guilty of conspiracy to murder, and six of conspiracy to cause grievous bodily harm.

The prosecution alleged that following the loss of their friend John, who was killed in the local area on 5 November 2020, the Manchester 10 wanted revenge for his death. Boy 1 caused direct harm to another (with Boy 3 present) a month later, and almost 2 months later, Boy 3 was present at harm with three unknown individuals. Was Boy 1’s harm a violent response to the loss of his friend? Yes. However, ten boys were brought into the dock under the guise of being part of a ‘conspiracy’ that led to that harm, and other ‘potential’ harms.

The boys were friends with John to varying degrees and knew each other in differing and disconnected ways. The time between his death in November 2020, and the harm of December 2020, was manipulated by the prosecution to form a ‘gang’ narrative.

A grief fuelled Telegram chat, active for just one day shortly after John’s death on the 8 November 2020, was constructed as ‘gang’ planning, despite none of those discussions leading to harm against anyone discussed.

For four boys, this was the only evidence, and for the others absent from harm, it was their grief, connections to drill music group M40, and low-level individual drug dealing for a minority, that was manipulated to say the Manchester 10 were, in fact, the M40 ‘gang’.

Joint enterprise

Their case mirrors many others in which young black people are imprisoned for harms they did not commit, often prosecuted under the legal doctrine ‘joint enterprise’. As described by Liberty, who with JENGbA (Joint Enterprise Not Guilty by Association), are taking the Crown Prosecution Service to court over the doctrine, joint enterprise sees that: ‘if one or more people commit an offence (the main offenders) and another/others (secondary offenders) intended to encourage or assist them to commit the offence, the secondary offender(s) can be prosecuted as if they were a main offender.’

However, while the Manchester 10’s case looks exactly like a case of joint enterprise, the doctrine was not used here. The use of conspiracy charges meant all 10 boys were principal defendants. For the majority, it was their words, not actions, that were deemed ‘criminal’: violence did not need to be proved. But the use of conspiracy charges against the Manchester 10 is not disconnected from joint enterprise and is possibly a result of its changing nature.

In February 2016, the case of R v Jogee resulted in a Supreme Court ruling which agreed that joint enterprise had been wrongly used for 30 years. Previously, ‘foresight’ that the principal defendant might commit the act was resulting in the conviction of secondary defendants. The Supreme Court found that this was unjust, responsible for many wrongful convictions. In theory, the Jogee ruling meant a jury must be sure of a secondary defendant’s positive intent that the principal defendant’s act should be committed.

While this was a hopeful shift, it also reflects why so many of us critique reform. Those harmed by the doctrine’s wrongful use are still not free, little has changed, and it opens the door for the same injustice to enter under a different guise.

Of course, conspiracy charges are nothing new, but in the case of the Manchester 10, the injustice is the space it now has to thrive in the ‘gang’ arena. Here, it allowed the prosecution to draw in a large net of young people where no fatalities had taken place, and where an attempted murder charge may have reduced the defendant list significantly.

For those who sent messages on a single day in November, the idea this could amount to an intention to murder felt unfathomable. But conspiracy helped reframe their inaction as assistance to the wider conspiracy. Conspiracy helped cage a large net of young people who had never harmed, with a final win at sentencing, when attempted murder guidelines were still utilised.

The ‘gang’ panic and the Manchester ten

The over-arching themes of the Manchester 10’s case, and others like it, require reflection and resistance. Becky Clarke and Dr Patrick Williams’ research on joint enterprise shows a ‘gangs’ discourse is more likely to be used when prosecuting black and brown men, and that ‘whilst some individuals recognised connections to their co-defendants […] the overwhelming majority contest that such associations reflect “gang” involvement’.

Six years on from the publication of their research, its key findings continue to play out in real time. The boys’ associations were constructed as ‘dangerous’. Despite some having never met prior to sharing a dock, the prosecution connected these boys through school, music, church, social media, and wove them together under the ‘gang’ label. The boys, in response, powerfully rejected this narrative.

Academics and organisers have frequently argued that the ‘gang’ is a racialised construct, solidified as a moral panic following the 2011 uprisings, where unrest due to another police killing was framed as a nationwide problem requiring an ‘all-out war on gangs’. Here began the journey to further control black communities through the development of discriminatory tools such as ‘gangs’ databases, a construct that would play a significant role in the movement of our young people from their communities to an expanding prison-industrial complex.

It has been hammered home by politicians and media that the ‘gang’ problem is a black problem. As David Cameron spoke of ‘gangs’ in his speech following the uprisings, he was not hesitant to tie the ridding of ‘gangs’ with a commitment to patriotism, or to utilise problematic stereotypes often associated with black families, such as ‘absent fathers’.

The work of politicians is reinforced by much media that reminds us through imagery and rhetoric of the same so-called threat. The ‘gang’ is ‘urban’, it wears hoodies, it likes rap and has many defining points (despite police having no definition at all), that in the minds of many, mean ‘black’. This all reinforced, as Williams explores, by community or criminal justice workers who act as ‘state-directed gang makers’, who perpetuate the same ‘gang’ mythologies to our black and brown youth: a role that holds great currency for those willing to partake in it.

Super-court

On top of this deliberately poisonous narrative, the police and prosecution had one more advantage on their side when it came to the Manchester 10. The trial would be one of the first in Manchester’s new ‘super-court’. Purpose built to put ‘gangs’ on trial, the new build within Manchester crown court cost £2.5 million.

With money that would be better spent on communities and invested into the lives of young people to reduce harm and address inequality, it is essential the new court stays busy to justify its presence in our city. It is built to prosecute ‘gangs’, therefore there must be ‘gangs’ to fill it. Its very existence furthers the moral panic of the ‘gang’ problem, and signals support for police to find more of them, or more aptly, to construct more of them, no matter how weak the evidence.

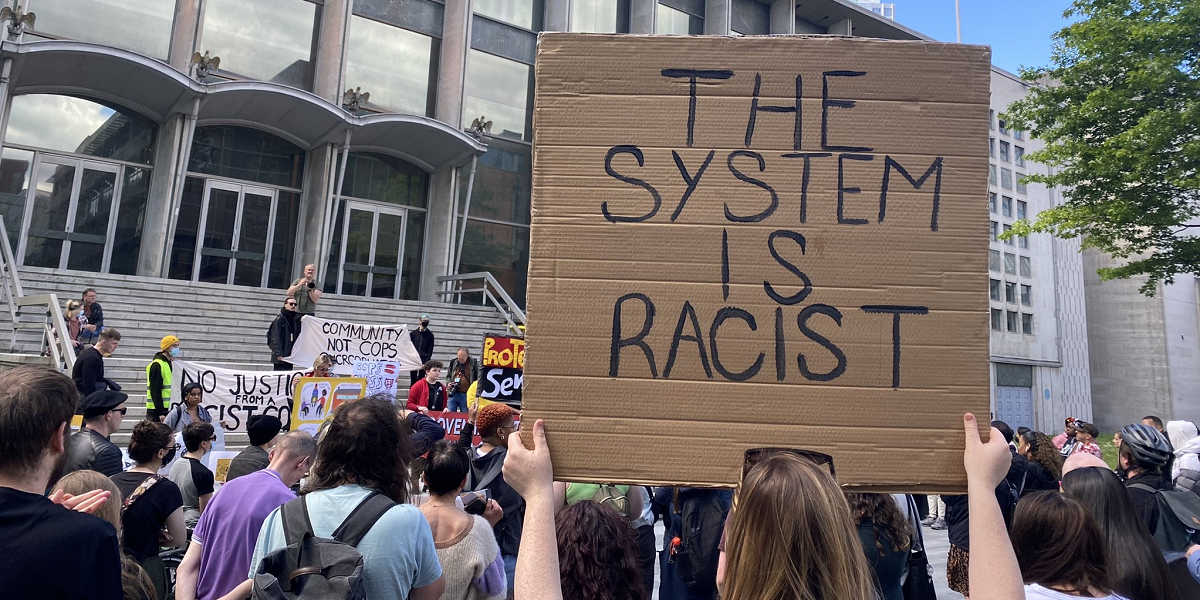

Protestors for the Manchester Ten on the day of the verdict, 28 May 2022

CREDIT: ROXY LEGANE

Once the ‘gang’ narrative sticks in court, nothing else is true. Counter-narratives from those taking the stand become nothing but cover ups to disguise a defendant’s ‘gang’ lifestyle. The narrative is so strong, that it has the power to convert everyday interests or cultures into ‘gang affiliation’, emotions or behaviours into ‘gang activity’. Where harm exists in cases, it becomes an organised feature of what the ‘gang’ was always set up to do, completely disconnected from how it may be explained by those responsible (or not) for it.

For the Manchester 10, grief, anger, loss, vulnerability, and state neglect ran through their testimony. Explanations came with apologies, accountability was taken by the minority responsible for harm, and for the majority more shocked by their presence at trial, pleas to be believed that their narrative – grief, not intention – was true.

Sadly, this case confirmed grief is not an emotion black boys are allowed to display, and they certainly do not get second chances. Their responses became ‘gang’ intention, not the words of young people not yet equipped – and certainly not supported – to deal with loss.

Prosecuting music

To further support the ‘gang’ narrative we saw an approach more frequently used in the US. ‘Prosecuting rap’, as Eithne Quinn, Franklyn Addo and others explore, sees rap lyrics used as evidence, supporting prosecutors to ‘bolster their cases, helping them secure convictions’. The Manchester 10’s jury had one key decision. Was M40 really a music group? Or was it in fact, one of the most dangerous ‘gangs’ in north Manchester?

A key theme of drill music is violence, that is a true and complicated reality. Complicated, because where many of us see creative expression, others see the threat that has been historically projected onto black music and communities. Complicated, because the idea of weapons, violence, and posturing to appear dangerous, in isolation means one thing, but can be made a key part of the ‘gang’ framing. In the case of the Manchester 10, a love for drill that was shared by co-defendants, particularly those closer to harm, became something different.

That violence, displayed thematically in lyrics, in photos with weapons, in YouTube videos, was sold as real to a society embedded in racist stereotypes. The words and performances of black artists are framed as literal, while those of white artists remain acceptable fiction. In court, some boys shared their knowledge of the genre, their hopes, talents, and desires to just join a friend’s music video. But any honesty in this regard was admission of ‘guilt’.

Responding to harm

That young people, individually and in groups, commit harm is not in dispute. What we must challenge is both the racist construction of a ‘gang’ through which this harm is supposedly committed and how we respond to such harms. Where policing and prison do nothing to reduce violence or keep our young people safe, abolitionist principles must lead us: to no children and young people in cages, and eventually, to no fatalities in our communities.

It strikes me that we will remain far from that goal until we are able to collectively do what is difficult and complex, and care for those who harm. When the Manchester 10 were found guilty, media coverage and outrage focused mainly on four of the boys, whose evidence amounted to sending messages.

I care about those boys deeply, but focus on them alone keeps us in a temporary position of shock, shock that passes quickly. Limiting ourselves to only caring about inconceivable injustice does not bring us any closer to building the infrastructure needed for collective healing for all.

It is complicated, but it is possible to care for all. We can build more meaningful justice for those who have suffered, whilst not subjecting those who have harmed to the racist, violent systems currently standing. Choosing to care for Boy 1, is not to say the harm he has done is acceptable, but it is the only way to learn how we move towards healing, and to stop perpetuating violence.

Viewing everyone as human is fundamental to our co-existence. Boy 1 is human, we must care for him: it is key to our resistance against a state that wants nothing more than black communities in prison. He is a teenage boy who was present at his friend’s death, who faced other challenges in life, and who is also more than that choice to harm. He is also good. He grew in a society that chooses not to support young people who experience cycles of violence and trauma.

A society that says the only solution to losses like these is to work with the police, an institution responsible for the everyday harm of those in our communities, an institution that kills racialised and working-class people without scrutiny, an institution we cannot trust.

What we need, is a deep, ongoing, proactive care which begins with those who do harm, and those who may. Accepting that people may act with violence in our society, and responding without judgement or punishment, is the only way forward to reducing and eradicating it. Acceptance dares us to consider what to do with our current reality.

Resistance to an increasingly violent state is tiring. It is going to take numerous different strategies; after all, joint enterprise and conspiracy charges are only one of the many tools at their disposal. But it will also be joyous, and we must dare to dream, because those dreams can be organised into the healing-centered responses our young people need.

Whether its Jahiem’s Justice Centre, Southwark Council’s commitment to zero exclusions (a thinking led by No More Exclusions) or the 500 community members who made community-based commitments to the Manchester 10 to support their release: our communities are showing that freedom is possible in our young people’s lifetimes.