In the mobile phone game Plague, Inc, players choose to be bacteria, fungi or bio-weapons and play as viral outbreaks. To ‘win’, they must evolve and proliferate. The game had enjoyed moderate popularity since its 2012 launch. Then, in early 2020, as Covid-19 spread through news headlines, Plague, Inc reached record numbers of UK downloads.

Over subsequent weeks, as lockdown loomed over us, apocalyptic virus films Contagion (2011) and Outbreak (1995) shot to the top of ‘most watched’ streaming platform charts. Amid crisis, people sought comfort, solace, even reassurance in disaster narratives. Filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar remarked at the time: ‘The current reality is easier to understand as a fantasy fiction than a realist story.’

Though often spectacular, pop culture representations of pandemics and other threats to humanity are not mere escapist fantasy. Rather, they reflect and shape (or skew) very real social anxieties, often with very real consequences.

Allegorical apocalypse

Few characters embody collective anxieties about pandemics, or other perceived social threats, as clearly as zombies, a term appropriated from Haitian folklore and popularised by US storytellers. Whereas bacteria and viruses – or indeed religion, culture and ideology – are invisible, monstrous assailants are comfortingly conspicuous, frequently defeatable through a bullet to the head. US ‘prepper’ groups ‘Zombie Squad’ and ‘Kansas Anti-Zombie Militia’ claim: ‘If you’re ready for zombies, you’re ready for anything.’ Their virulent logic has spread. As coronavirus cases rose in 2020, gun sales spiked.

Writers have used the ‘undead’ as allegorical devices for centuries. Mary Shelley’s 1823 novel Frankenstein: or the Modern Prometheus reflected contemporary debates and fears around science, religion and morality to warn against men acting as gods. Its reveal that man, not monster, is the true threat to humanity, remains a popular zombie story device.

Racialised blame for illness has led to xenophobic panics, forced quarantines and coercive state controls throughout history

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), in keeping with vampiric creatures found in millennia of folklore, reflected different social fears. Its eastern European aristocrat-predator, who seduced men and women alike, embodied xenophobic anxieties about foreigners infecting society, including through evoking the anti-semitic blood libel trope.

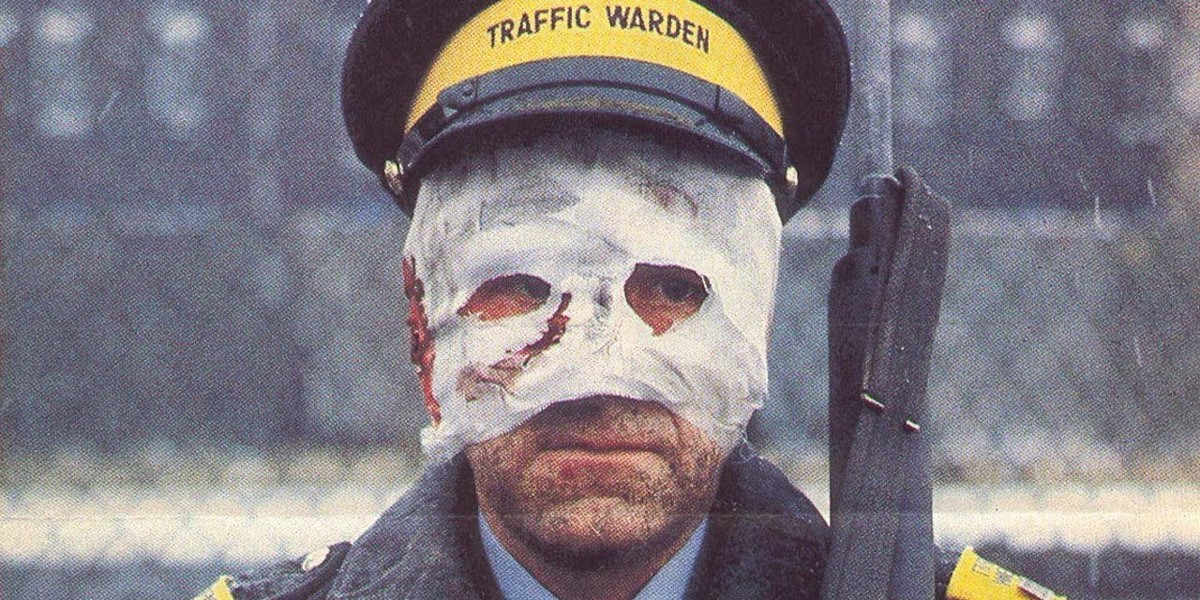

For Penny Crofts and Anthea Vogl, figures between life and death ‘transgress borders’, a framing that has been literalised to insidious effect, especially in genre films post-9/11. In World War Z (2013), for example, walls around Jerusalem provide defence against outside threats. Its breach heralds rapid, violent infiltration. The visual language of that film – echoed in the internment camp of The Girl with All the Gifts (2016), the fences of Land of the Dead (2005) and the shuffling ‘hoardes’ of countless recent titles – replicate dehumanising real-world depictions of refugees as ‘waves’, ‘floods’, ‘swarms’ and vectors of disease.

The similar allegorical power of apocalyptic ‘alien invasion’ sci-fi speaks for itself. ‘Outsider as threat’ framings also shape pandemic coverage. Be it the ‘Spanish flu’, ‘Asiatic cholera’, or Donald Trump‘s ‘Chinese virus’ Covid slur, racialised blame for illness has led to xenophobic panics, forced quarantines and coercive state controls throughout history.

Life in ruins

During lockdown, pop culture representations of desolate city landscapes similarly penetrated popular consciousness, prompting photojournalist Jonathan Jones to remark that ‘sci-fi has spent more than a century preparing us’ for such scenes. As stills of eerily empty London streets from 28 Days Later (2002) became a British news media staple, US editors looked to 12 Monkeys (1995) for shots of Philadelphia deserted following a fictional viral outbreak.

In post-apocalyptic fiction, a city in ruins is an effective shorthand for the total destruction of a way of life that is unmistakably our own. Such imagery particularly resonated in post-war decades of extreme nuclear anxiety. Then, the potential devastation of nuclear war loomed large alongside more imaginative fears of monstrous mutations caused by atomic experimentation – from the radiated giant ants of Them! to the enduring behemoth Godzilla (both 1954).

Cold War anxieties similarly charged more quietly apocalyptic infiltration stories such as Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). By the 1980s, decades of doomsday clock-ticking culminated in the global production of overwhelmingly pessimistic fallout films, from the Japanese Barefoot Gen (1983) and Black Rain (1989), to the Soviet Dead Man’s Letters (1986), to the British Threads (1984) and US movie The Day After (1983) – both films credited with turning political heads towards detente.

CREDIT: DNA FILMS

For art historian Dora Apel, writing in 2015, recent proliferations of city-ruins aesthetics reflects a widely felt cultural pessimism produced by the failures of capitalism. Real world urban decay is associated with rising poverty and inequality, declining wages, inadequate health and social care, unemployment, homelessness and ecological disaster. For Apel, modern fascination with urban ruins reflects fears that worse is coming. Yet such scenes can also promise possibilities of transgression, of a blank slate from which green shoots may emerge – the literal narrative of WALL-E (2008), a ‘cautionary dystopia’ about hyper consumerism and environmental degradation disguised as a child-friendly tale about robots and friendship.

In fiction, overgrown, desolate city ruins also usefully denote a significant passage of time between an apocalyptic event – be it a nuclear, viral, environmental or unnamed catastrophe – and the storyline in focus. This temporal trope may indicate a belief that humanity requires time to ‘heal’, or that total annihilation is required before a new world can be built. It also points to a reality that can be difficult to present in compelling terms: humanity-threatening disaster can coalesce at a glacial pace, as climate change scientists and activists well know.

George Marshall argues that our brains are ‘wired to ignore’ the narratives that rule most fact-based climate change media: complex science, uncertain outcomes and calls for personal sacrifice with intangible rewards. While daunting in magnitude, the threat of climate change is ‘exceptionally ambiguous’, says Marshall, with no obvious ‘external enemy with an intention to cause harm’. Storytellers concerned with ecological emergency, however, seem stuck between two posts, as bombastic dystopian climate fiction – ‘cli-fi’ – can cause alarm to the point of incredulity and paralysis.

The hope is that storytellers and audiences alike look beyond dystopia to make sense of social anxieties and apocalyptic realities

The compelling yet scientifically shaky vision of ‘abrupt global cooling’ from The Day After Tomorrow (2004) undeniably tapped into global mainstream consciousness – generating ten times more US news coverage than the most high-profile contemporary climate research report. Nearly two decades later, amid deadly heatwaves, cold snaps and ‘extreme weather events’, the film still dominates pop culture imaginaries of catastrophic climate change. Cli-fi frequently depicts humanity on the brink of disaster, featuring an ‘ignored expert’ – be it scientist, alien (The Day the Earth Stood Still, 2008), archivist or psychic everyman (Take Shelter, 2011), but usually white and male – whose warnings of impending destruction are fatally ignored. As catastrophe unfolds in real life, these films may be seen as cautionary tales. Conversely, cynicism about humanity’s ability to respond to identified dangers – made explicit in Don’t Look Up (2021) – may evoke feelings that calls to action are only doomed to fail.

Cinematic pandemics likewise play out at speed. Contagion (2011), hailed as ‘realistic’ on release, saw its virus spread to 26 million people within days. The outbreak of 28 Days Later saw total social collapse within a month. I Am Legend (1954), and its numerous film adaptations, feature a swift, near-total destruction of the species. These stories frame panic and survival-mode thinking as both necessary and inevitable responses to crisis. Yet, even in an age of hyper-mobility, it took four months for Covid-19 to register one million global infections. That recent experience of a slowly unfolding disaster revealed that action to avert catastrophe is possible – and that the wrong choices can be fatal.

Post-apocalyptic possibilities

Arundahati Roy wrote in April 2020: ‘Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.’ Hopes that more fair and caring societies would emerge from recent experience may have proven overly optimistic. Signs exist, however, that new narratives are being embraced, particularly in the world of gaming – with potential to shape new responses to looming crises.

During the pandemic, the popularity of Nintendo game Animal Crossing: New Horizons revealed a shared, global enthusiasm for collaboration and kindness in quotidian interaction, as millions of players built new societies on virtual islands – featuring protests, memorials, marriages and a wealth of gift exchanges. The latest version of Plague, Inc lets players try to save the world, not destroy it.

Minecraft, played by 91 million people globally each month, recently introduced climate change mechanics, including carbon dioxide emissions into its open world setting.

Civilization VI: Gathering Storm, released in 2019, likewise challenges players to keep their carbon emissions down, while navigating global diplomacy, climate treaties and new carbon-neutral technologies. In their review of the game, Luke Plunkett concluded: ‘Being put in charge of an attempted solution to climate issues, even in an abstract fictional one like this, is a refreshing change from letting increasingly bad news wash over me like, well, a rising tide.’

Recent years have taught us that life under lockdown does not feel like a zombie movie. Viruses cannot be felled by guns; nature will not ‘heal’ on its own. We have wept for the ill and dead, and seen that survival demands cooperation, not exclusion, or fear. As new viruses prompt contagion measures, new wars cause devastation and displacement, new climate changes cause fire and flood, the hope is that storytellers and audiences alike look beyond dystopia to make sense of social anxieties and apocalyptic realities. After all, the media we make and consume can compel how we act in the world.

Research for this article was funded by OKRE.org