The South Indian thali we had for lunch that day was exceptional. It had been one of the first sunny, bright blue sky days of the year and as we drove through Evington and Highfields even the ‘dark factories’ glistened. Along East Park Road, Vaisakhi decorations wove through the streetlights, Holi celebrations had begun the day before in Spinney Hill park, and women in burqas pushed prams and chatted together as they walked up to the Nishan Sahibs at the mouth of the road in front of the iconic old Evington Cinema building.

This is Leicester. An exotic city, a diverse city, a city that is home to an array of racially minoritized (RM) populations. Just six months later, the city made national headlines for the ‘riots’ that took place; masked gangs marched through East Leicester targeting Muslims in what can only be described as ‘Hindutva-inspired Islamophobia’. So Leicester is also a ‘beseiged’ city, a segregated, racialised city; it is a city that has been made ‘dirty’ by the positioning of RM people as out of place in their own home. This story of Leicester, the neglect of its RM people and garment workers, became better known during the pandemic when Leicester became the first UK city to face a local lockdown in 2020. Now an ‘open secret’, Leicester’s ‘garment district’ was penned in as if plagued.

Racialised governance

This is what we call ‘re-colonisation’. On 18 March 2022 we met in a room in Highfields Community Centre that looked out over the rooftops of Highfields and Evington. The location was important. The Centre offers proximity to the factories and many RM communities, it is embedded in recolonisation – its effects and resistance. The day was important too, Holi – the vibrant, colourful, theme of which made a stark contrast to the backdrop of a city made ‘dirty’.

We sat around the table with our backgrounds in academia, activism, local politics and community action. We were there because we want to highlight the tactics of racialised governance that Leicester is experiencing, as visible in the state neglect of factory workers, and to reclaim the city from ‘the mire’ to a home for and made by immigrant communities. This can only happen through ‘community governance’, which Tarek Islam of FAB-L (Fashion-workers Advice Bureau Leicester) defines as simply ‘helping people’ through providing basic advice and support.

Such help is a powerful indictment for the role of rights in addressing Leicester’s recolonisation ‘crisis’. Rights cannot do the work of remedying the debilitation experienced by factory workers – who, according to Claudia Webbe MP, are kept in a cycle of fear and compliance. Jobs are given as a ‘favour’ and working conditions can be dire, with women working 12-hour shifts in unheated factories. The unions are unable to penetrate a system where ‘resilience’ has turned to ‘subservience’. These conditions have been extensively documented by Nik Hammer and his research team. But rights, explained Islam, take on a policing role – ‘we cannot go in as the factory police and just say “yeah – we’re here to solve your workers’ rights issues” because there’s a lack of trust from within the community’. Being paid £2 or £3 an hour and remaining silent for fear of being labeled an informant has become normalised.

Race and class

FAB-L seeks to adopt a different strategy; one that provides support and builds trust because this is the only path to empowerment for workers. Trust is about more than the conversations about rights – it’s about creating an environment where people feel safe to ask for basic help with, for example, the poor housing conditions that feed the exploitation in the first place.

These stories are not unique to Leicester: exploitation abounds in the UK’s gig economy. Leicester’s recolonisation is about race; about racialised people who have been ‘silenced’ as well as the racialised nature of capitalism and labour. ‘To what extent’ asked Jayanthi Lingham, a partner in the Co-POWeR Project ‘is this about workers and the capitalist moment rather than about [the] Asian men [running the factories]?’ How is it that Boohoo can get away with minimalist inspection practices while the problem is constructed as one of factories run by brown people?

Priya Thamotheram, head of Highfields Centre, expressed surprise that some people remain ‘hung up on the idea of skin colour… and colour consciousness’; what this is about, rather, he argued, is ‘the structural relationships that those individuals occupy in terms of their societal positions … Asian businessmen are no more generous or wicked than [others]’. But it is not just about class – for Thamotheram it is about how race is coopted into a class structure. And, as Webbe points out, the issue is also gendered. Not a single factory in Leicester is under female management. To rephrase Wendy Brown, ‘it is impossible to pull the race out of gender, or the gender out of sexuality, or the colonialism out of caste out of masculinity out of sexuality.’

Radical friendship

This poses huge challenges: How do we speak (literally and metaphorically) to those RM communities the state has abandoned? There are about 700 garment factories in Leicester (the true number is unknown and constantly changing) and around 10,000 garment workers. How do we reach them? What place do they have in a city gentrifying and recolonising around them? Webbe outlined three very clear ‘solutions’: a) a legislative change on garment trading in the form of a garment trading adjudicator b) consumer change on fast fashion; and c) a greater role for unions and community centres, such as Highfields.

It is at this latter site that we proposed something different: a response to recolonisation through radical friendship. The FAB-L project represents friendship as a set of practices that are concerned with fighting back through building relations, trust and care. ‘Through actions we want to solidify the trust’, says Islam. It is the trust and empowerment that is important, not the legal labels or limited remedies. Speaking with people, being silent so you hear them, talking to them as individuals and not statistics. Of course actual change is an objective too –speaking to one worker meant FAB-L were able to reach out t0 ‘the brand’, that reached out to the factories, and a real pay increase was achieved for all.

In contrast, calling the Leicester situation ‘modern slavery’ does not actually address working conditions; in fact, focusing on the exceptional draws attention away from systemic harm. Following our Salon, Webbe tabled an Early Day Motion about FAB-L in Parliament, praising its ‘holistic approach’, from tackling low wages, support with benefits services and domestic violence, to help with form filling. ‘Basic help’, as Islam called it, which he learned at a young age in his local community.

Fighting harm will not come through more police powers or legal rights; it will come through trust, through community organising and friendship

FAB-L has since increased its own community-facing activities, working with Labour Behind the Label, to screen a documentary on the historic struggles Leicester’s fashion workers and holding a launch event. This is a making-visible, telling the story through friendships built between factory workers and their descendants. It breaks the inevitable cycle of exploitation and recolonisation through basic help, which Islam and his parents lacked. And it is more vital than ever in a deepening cost of living crisis.

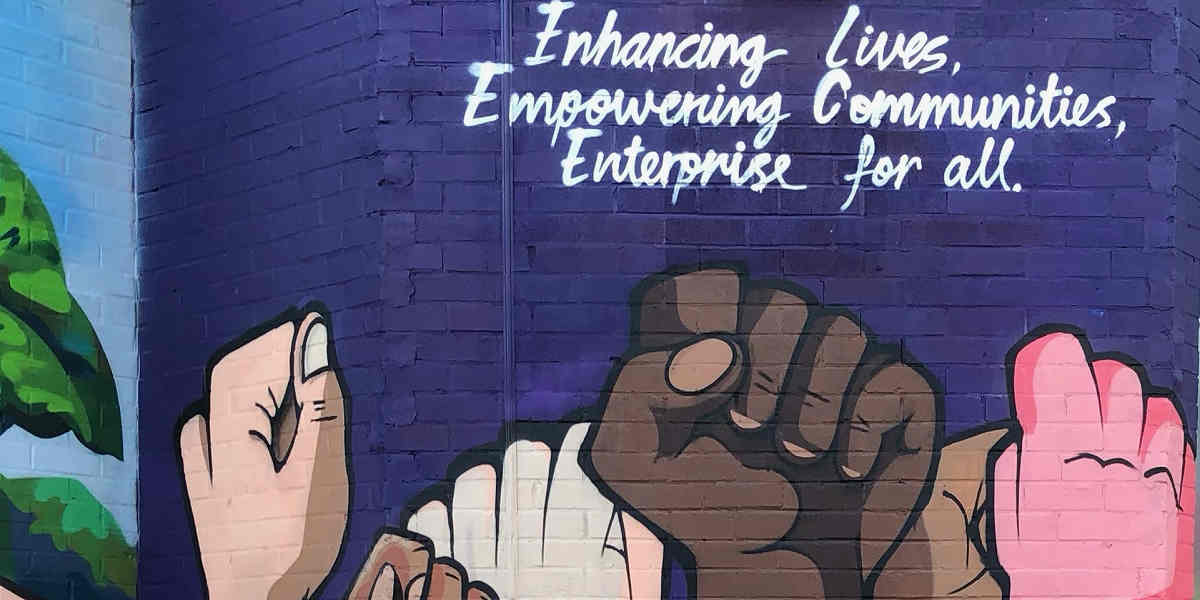

There is a mural outside Highfields Centre where we all posed for a souvenir photograph of the day. Painted in a myriad of colours, showing fists raised in resistance, it says ‘Enhancing lives, Empowering Communities, Enterprise for all’. It was a fitting end to the day, to feel we had connected, that resistance to the recolonising of Leicester will continue. As the recent violence has shown, fighting harm will not come through more police powers or legal rights; it will come through trust, through community organising and friendship.

Special thanks to my project partner, Ben Rogaly; thanks to the participants of the Salon event: Ben Rogaly, Tarek Islam, Jayanthi Lingham, Nik Hammer, Fatima Rajina, Priya Thamotheram, Claudia Webbe; and to Nadya Ali, Shirin Rai, Chris Slowe and Ben Whitham for their individual conversations with me.

The project ‘Pandemic, Race and Rights: How Covid Re-Colonised Leicester’ is funded by the ESRC IAA scheme, University of Sussex.