When sociologist Ruth Glass coined the term ‘gentrification’ in 1964, she was analysing how previously working-class areas of London were being taken over by middle-class residents. Since then, scholarship has expanded on gentrification as a post-industrial process occurring in cities in the global north. Gentrification changes the way a neighbourhood looks, feels and sounds. Usually when people talk of gentrification they are speaking of the city, and the many ways gentrification occurs in inner-city neighbourhoods. Often, these are multicultural locations, and places that have experienced disinvestment, loss of employment and a downturn in living standards.

For a wealthier demographic, keen on city-centre living, these areas, once deemed to be ‘undesirable’, now offer an opportunity for redevelopment and capital accumulation. It is a way to create a suburban lifestyle in an urban setting.

On the surface, gentrification can seem like a positive step as more money flows into an area and the quality of housing stock improves. But subsequently, rising accommodation costs change the community’s makeup, as being able to buy or rent property inevitably moves beyond the reach of lower-income residents.

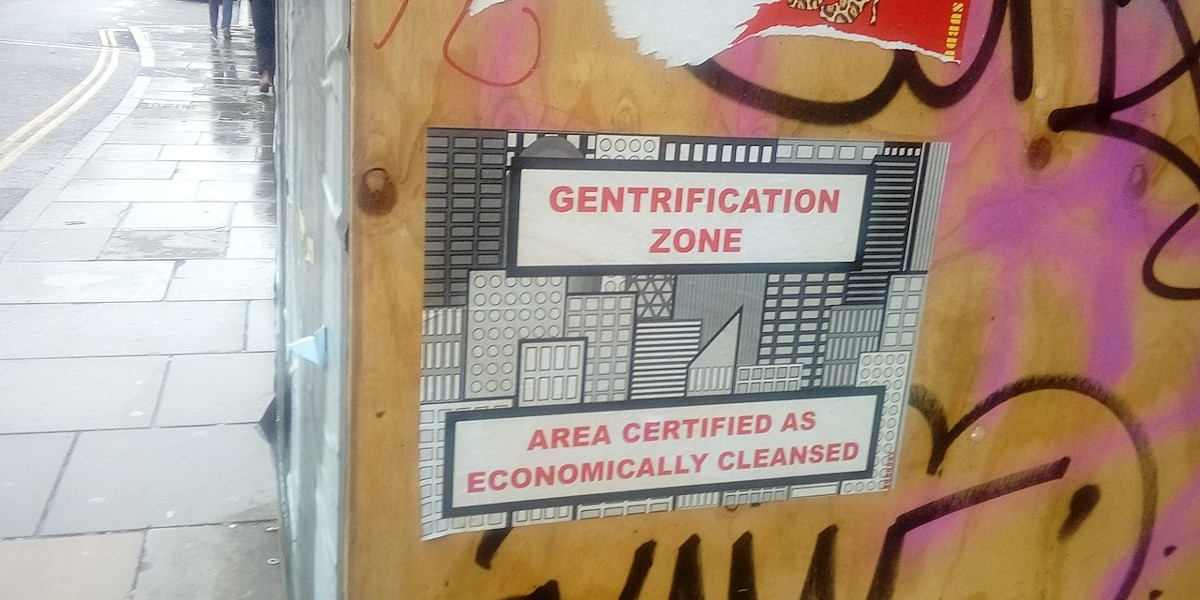

Another strand to gentrification is how policy and economics work together to push out existing residents. Cash-strapped local authorities clear a path for wealthier communities as they pose less of a pull on scarce resources, often leading to the creation of socio-economic silos. As access to leisure and social activities are determined by cost, opportunities for social mixing are limited. And in the production of gentrified urban space, as separate spaces and places have replaced integration, communities become polarised.

Separate spaces and places replace integration, communities become polarised

In gentrified environments, we may not necessarily see ostentatious displays of wealth, but status is nevertheless conveyed in subtle ways. In the pursuit of bringing a more genteel life to the inner city, railway arches become coffee shops and artisan bakeries, weekly farmers’ markets and gastro pubs appear, and corner shops shift from fast-moving consumer goods to high-cost organic produce. Spatial barriers between rich and poor are evident in access to leisure, ‘poor doors’ and the use of public space.

While gentrification may increase the economic value of an area, it also amplifies and intensifies how some communities have been rendered out of time and place. Wealthier residents are generally removed from the daily realities of life for lower-income communities.

In gentrified areas, people live with these differences in a way that can be categorised as ‘separate together’. The multicultural nature of inner-city areas is often erased, or positioned as a backdrop to the desired urban village. In the rush to ‘improve’ an area, little value is placed on the contributions of existing communities, and less attention is paid to the ‘deep cleansing’ of communities and the consequences for those who are displaced.

Further reading:

- Ruth Glass, ‘Aspects of Change’, in London: Aspects of Change (Centre for Urban Studies, 1964)

- Loretta Lees, Tom Slater, Elvin Wyly (eds), The Gentrification Reader (Routledge, 2010)

- OSOM, ‘Losing My Home in The Name Of Regeneration’ (2019)