Sai Englert’s new book is a brilliant introduction to settler colonialism. Yet beyond this, Englert also provides a political blueprint for understanding settler colonialism within capitalist development and engaging with struggles against it. Englert is an academic focusing on settler colonialism and settler labour movements. Both in and outside the university, he has been a long-term advocate for the Palestinian liberation movement. He is also an editor of the workers’ inquiry journal Notes from Below, and his latest book amalgamates these different parts of his life. Drawing out the socio-historical complexities of settler colonialism, Englert offers a practical politics that seeks to link indigenous struggles to that of struggle against capitalism as a whole.

An ongoing process

From the onset Englert shows that settler colonialism is not a historical process but an ongoing one. Reference to settler colonialism must account for ongoing indigenous struggles against dispossession, which are shaping how capitalist social relations are evolving. As Englert puts it: ‘Understanding settler colonialism is a crucial aspect of making sense of the world in which we live as well as the ongoing struggles to change it.’

Throughout the text Englert hammers home the political importance of this point. Echoing existing critiques on settler colonialism as overemphasising settler states’ stability – and in doing so concluding that colonialism is a fait accompli – Englert shows this is far from the case. By seeing settler colonialism as an ongoing process of struggle, Englert not only allows us to understand how contemporary global society works but also presents an abundance of political struggles to be engaged with.

Englert offers a practical politics that seeks to link indigenous struggles to that of struggle against capitalism as a whole

Following on from this strand, Englert rejects the idea that settler colonialism is solely defined by the ‘elimination of the native’. Rather, for him, settler colonialism is not a homogenous process that can be linked exclusively to one form of domination. While elimination of indigenous populations is certainly a part of many processes of settler colonialism, it is a long way from being the only piece of violent apparatus at the settler colonialist’s disposal. Through analysing various cases from around the globe, Englert demonstrates how both indigenous elimination and indigenous exploitation have developed in different settler-colonial contexts.

Accumulation through dispossession

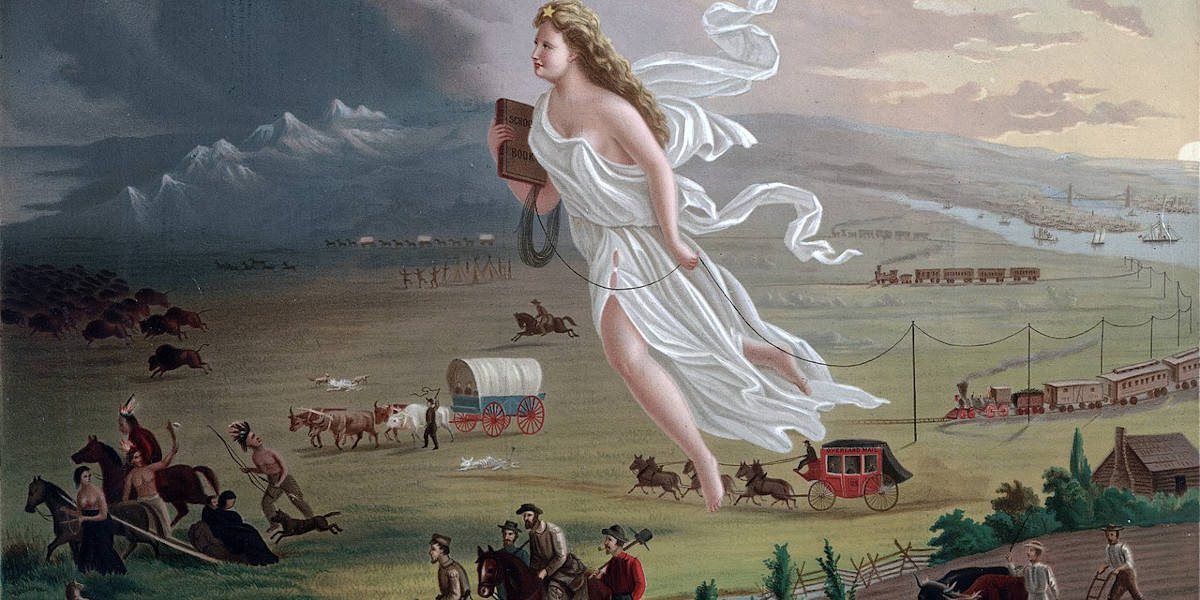

What different processes of settler colonialism do have in common, though, Englert suggests, is a relation of accumulation through dispossession necessary for the ‘deepening and expanding’ of capitalist power. In the first half of the book, he lays out how these processes of accumulation and dispossession emerged in much of the world, where indigenous people were pillaged, enslaved and massacred by colonial forces. Englert also explains how these processes were intimately intertwined with processes of dispossession in Europe, where the enclosure of common land created the urban working class we know today.

He expands upon this, explaining the emergence of racism as a form of social control that, among other things, helped produce, and reproduce, a settler subjectivity. One example he uses is the migration of the urban poor from Europe to settler colonies in North America. Originally coerced into migrating through poverty and/or persecution, a system of social control had to be put in place to maintain order among these settler-labourers and prevent them from joining with enslaved populations in challenging of settler elites. Material benefits were designated for those included within the elite’s definition of the ‘white race’, and so reinforced a settler subjectivity that cut across settler class boundaries and necessitated further indigenous dispossession.

Race is obviously then, Englert explains, a social relation that has been constructed in different forms in different localities for different purposes. However, he asserts that the discovery of the social construction of race does not mean it ceases to exist; only the practical dismemberment, through political struggle, of those dominant social relations that produce race, can do this. As he puts it, ‘The ongoing existence [of anti-colonial uprisings and revolutions] points to the limits of racism as a social stabiliser.’

It is these chapters where the book stands out by most obviously demonstrating the materialist character of Englert’s analysis: understanding settler colonialism not simply as an evil of mystical source, but rather one with tangible social relations driving its development, and, conversely, being constantly challenged and reshaped by indigenous struggles against it.

(De)stabilising settler-states

The final chapters of the book consider class conflict within settler-states. While not denying the capacity for settler labour movements to express unity with indigenous struggles, they present a bleak picture of the historical precedent for such events. Through dissecting the dominant social relations driving labour struggles in settler states, Englert demonstrates how time and again settler labour movements have struggled for greater dispossession of indigenous populations for their own benefit. Indeed, he shows how on many occasions militant settler labour movements have struggled against the plans of settler capital to further integrate indigenous populations into the labour force, and thus acted as a stabilising force for settler states.

While elimination of indigenous populations is certainly part of many processes of settler colonialism, it is not the only piece of violent apparatus at the settler colonialist’s disposal

While Englert’s presentation of the socio-historical problematic of the striking settler is enlightening, it would have been interesting for him to have explored the political ramifications of this further, particularly with regard to the political possibilities of new forms of subjectivity being produced that could encompass indigenous and settler labour populations together against the settler state.

This understanding of settler labour as a contemporary stabilising factor follows on to the final chapter, which locates indigenous resistance as the key destabilising factor in settler states. Englert analyses contemporary examples of indigenous resistance, first in Palestine to settler-colonial occupation, then in North America against pipeline projects. By going through the timelines, tactics and visions of these indigenous struggles, he presents a picture of how localised struggles enable these communities to produce a generalised vision for the abolition of capitalist social relations.

Writing a book on this topic is a grand task, and certainly Englert, of his own admission, does not cover every single form of settler colonialism to have occurred or that is occurring. But while the title claims the book is an introduction to the topic, it manages to go much further. Through a compositional analysis of ongoing processes of settler colonialism, linked within a framework of capitalist dispossession and accumulation, Englert presents much food for thought on how struggle drives development and subjectivity.

The message is powerful and clear. We are not passive subjects in the development of global society; our struggles can and do change what the future holds.