Funding

In the past 14 years, funding for the arts has been drastically cut in real terms at both national and local levels. Analysis by the Campaign for the Arts and University of Warwick shows that in 2022/23 government Arts Council funding was down 18 per cent in England, 22 per cent in Scotland, 25 per cent in Wales and 66 per cent in Northern Ireland since the start of the 2010s. In response to national reductions in local government expenditure, between 2009/10 and 2019/20, investment in the arts by local authorities in England fell by more than 30 per cent.

In its 2021-24 Delivery Plan (2023 update), Arts Council England (ACE) announced that it would be investing in a new cohort of national portfolio organisations (NPOs), investment principles support organisations and creative people and places partnerships from April 2023. It claimed that ‘a much wider range of individuals, cultural organisations and communities will be benefiting from public investment in creativity and culture’.

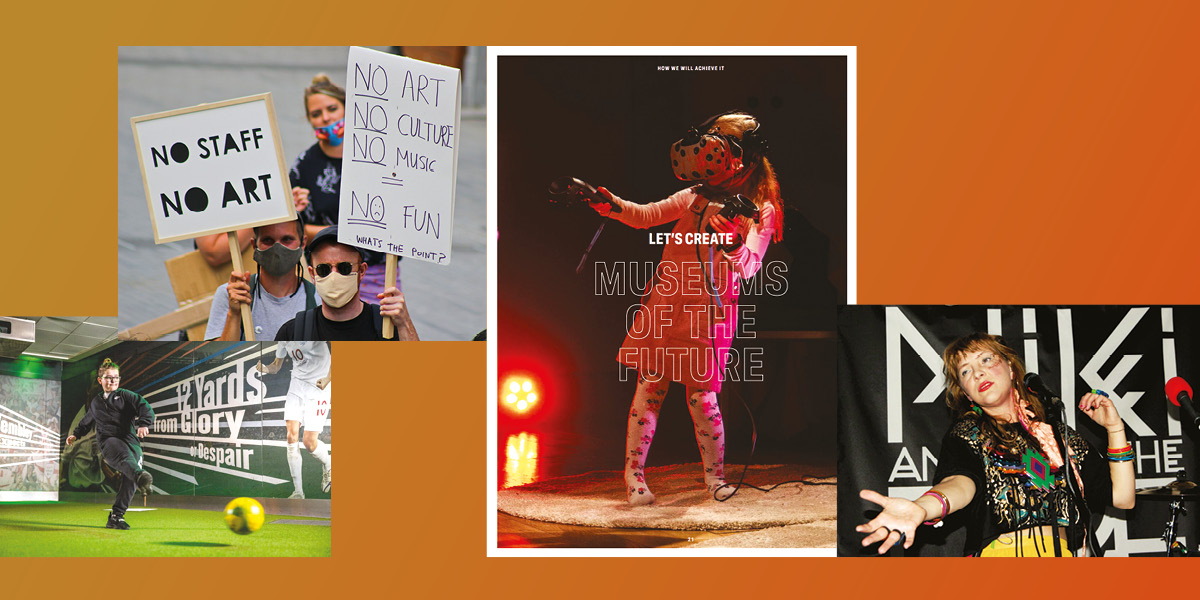

As a result, ACE will divide £446 million between 990 organisations during 2023-26. New recipients include those who fall under an expanded understanding of culture, encompassing those representing traditionally working class or popular culture – such as Blackpool Illuminations and the National Football Museum – and reportedly comprise an increase in women and black, Asian and ethnically diverse people in leadership roles across the whole portfolio.

Impact of COVID-19

Despite the ACE awards, creative sector workers report that smaller and emergent organisations have struggled to secure funding to survive post-pandemic. With the cost-of-living crisis, even institutions that won NPO status have to stretch their funding further to meet rising bills before supporting artists and commissioning works. Grassroots music venues have been in decline since the mid-2000s and, during the pandemic, saw losses in the live music workforce (technicians, sound engineers etc) due to the lack of financial support for freelance workers during the national lockdowns. In this period, researchers heard that some of these workers retrained or accepted more secure employment, choosing not to return post-pandemic, creating a deficit of skilled workers in the industry.

The survival of the night time economy has been much discussed, with the number of workers in the sector nationally falling from 9.5 million in 2016 to 8.7 million in 2022. Readers might recall Greater Manchester night-time economy advisor Sacha Lord’s digital billboard sporting a photo of then-PM Rishi Sunak, accompanied by the words: ‘I ignored 3.8 million self-employed… because they didn’t vote Tory’ sited across from the venue of the 2023 Conservative Party conference in central Manchester.

Funding for arts organisations was reportedly swiftly re-framed (or, to use the buzzword of the period, pivoted) during the pandemic to fund initiatives that focused on community-engaged projects, particularly those aimed at typically marginalised groups. While the intention appears commendable (to support ‘hyperlocal’ communities), it has meant that organisations not adequately equipped, or simply undertrained, to support community-focused work were suddenly competing to undertake projects. These funding schemes were among only a few sources of income available for the organisations to bid for. Research into the impact of Covid-19 on the creative industries also reported that resources for maintaining buildings and collections were non- existent, impacting local authority institutions with collections already struggling to survive on minimal resources.

Today, the organisations that have not benefited from recent ACE funding use crowdsourcing or spend time applying for competitive charitable funds to support their development and provision. In the Arts Hustings 2024 we heard from the Labour representative, Chris Bryant, that philanthropy has dried up, except in London and the south east. Dependence on donors and sponsorship can raise further issues for arts organisations, with reliance on corporate money leading to unwanted associations with businesses choosing to ‘artwash’ their image, as we saw with BP and Tate.

In this funding climate, institutions could be forced to make decisions that compromise their ethics and damage to their reputations or face closure. ACE funding also includes £43.5 million each year for the Levelling Up for Culture Places (LUCPs) scheme – investing in places that ACE has historically overlooked – but with the Labour government’s announcement that the ‘levelling up’ terminology will be erased, future funding plans and schemes for these under-represented areas is unclear.

Arts education and the creative workforce

For a number of years, arts and humanities education has been under attack in the UK. This has been seen in the prioritisation of STEM subjects in compulsory education and the Conservative government’s repeated references to ‘low-value’ degrees (read: arts and humanities) in higher education. The impact is seen in the numbers of pupils who choose arts subjects. Since 2010 there has been a 43% decline in arts GCSE entries and a 26% decline at A Level. The introduction of the new Welsh curriculum, with arts and creativity centred (humanities and expressive arts form two of six areas of learning and experience), is a welcomed respite from the negative narrative.

The Campaign for the Arts reported that, in its 2024 campaign materials, the Conservative government identified arts and creative courses as ‘not among its strategic priorities’. And since April 2021, HE providers received 50% less funding from the Office for Students for these courses. In July 2023, Rishi Sunak announced a policy to cap the number of so-called ‘low-value’ degrees that do not have a high number of graduates going into postgraduate education or professional jobs. As arts graduates do not always have a clear path to a ‘professional’ job – for example, some work part-time to support a studio and freelance artist career – the changes presented a clear ideological attack intended to devalue an arts education.

Further, in April this year, the then-education secretary Gillian Keegan announced the freezing of top-up funding for creative and performing arts courses for 2024 25. Due to inflation, this represents a real-terms cut to funding that had already been almost cut in half in 2020-21 by previous education secretary Gavin Williamson. The impact of these cuts can be seen in the closure of arts and humanities departments and creative courses across UK universities. These include Goldsmiths, historically heralded for its innovative art education and a key institution in the history of Blair’s ‘creative Britain’ through its association with the Young British Artists.

Grassroots and new government

The downgrading of arts subjects in HE does not correlate with the labour market for the creative industries, which employ more than 2.3 million people in the UK, generating £10.8 billion a year, according to the most recent government figures. Of course, there remain huge inequalities in who gets these jobs, with working class women of colour facing the biggest barriers to entry. The growth of organisations dedicated to addressing these inequalities (such as the charity Arts Emergency, the talent development agency for underrepresented talent, Story Compound, and the Second Act gallery in London, which focuses on the inclusion of northern and working-class artists) demonstrates the need for support within the industry beyond what Arts Emergency has referred to as the ‘old boy network’. In the face of increasing tuition fees and other barriers to access, we have seen the emergence (and closure) of alternative peer-led art schools across the UK (School of the Damned and now-closed Islington Mill Art Academy), including those dedicated to a postgraduate education (the Other MA, Southend-on-Sea).

In cities in the north of England, the grassroots provision of studios, working and exhibition spaces demonstrates the lack of subsidised, affordable facilities available for arts graduates. These include Islington Mill, home to more than 100 residents and collectives, which has retained – and secured funding to develop – its home in Salford for almost 30 years. Founded by one man, Bill Campbell, who wanted a space to make art in the city, the Mill has grown into a hub for Manchester and Salford’s independent arts scene. Retaining a DIY ethos, the Mill is now home to a range of makers and creatives, including design and fabrication companies, furniture-makers, fashion designers, TV production and artist-led organisations such as Short Supply, which creates opportunities for emerging and early-career artists. Most recently, Short Supply has partnered with DMZ Studio (an early career artist collective in Manchester) on the Made It 2024 Graduate Art Prize aimed at arts graduates in the north west.

In a recent public discussion at the Castlefield gallery, Manchester, representatives from or with histories of artist-led organisations in the region talked about the continued distance between the larger organisations (often with larger ACE grants or similar) and the grassroots ones. Artist-led and grassroots organisations have strongly felt the impact of the economic changes in recent years, including the higher rents, lack of space and gentrification processes that force out artists after they have deposited their cultural value in a location, alongside the other issues mentioned above. A number of these organisations emerge or develop projects to support underserved or marginalised groups within the arts.

The discussants stressed that, to develop the region’s arts provision (particularly visual arts), artists needed to be listened to by those funding and supporting the development of culture. They asked for space to experiment, to take risks and to fail, things that often seem unaffordable but are essential to creative development. This raises the question of what those in power can learn from the creatives whose work they aim to support.

Time will tell what we can expect from the new government, but the creative industries are foregrounded in Labour’s plan for an industrial strategy, acknowledging the potential for growth in this area. The party was quiet about funding for the arts during the election. It did, however, pledge in its manifesto to review the curriculum to support and emphasise arts education and to set up a national music education network. Reference to higher education was vaguer – Labour seems to understand that the current provision does not work, but there was no clear plan as to how this might be resolved, particularly in the face of so many humanities department closures.

In his post-election blog post, Arts Council chief executive Darren Henley wrote: ‘At the time we swiftly and unequivocally clarified our support for artists to make challenging political work, and we will continue to hold fast to that position.’ And, in her first week in post, the incoming culture secretary, Lisa Nandy, boldly proclaimed that ‘The era of culture wars is over.’ Henley further noted that, ‘We have, of course, heard and heeded the warnings from the incoming Treasury ministers that there are severe pressures on the public purse.’

So, in short, the message is that government funding for the arts is unclear and unlikely to increase in the near future. We might ask how plans for devolution will affect this funding. Will local councils see the value of investing in the arts or will it be up to grassroots initiatives to make sure that the under-represented communities of creatives remain served? Does the scrapping of ‘levelling up’ mean the loss of those funding initiatives that support culture in economically poorer areas of the UK?

The message about arts education is clearer. This government sees the value of the arts, both socially and economically, which should show some shifts in attitudes towards and take up of creative subjects and, hopefully, provision in the coming years.