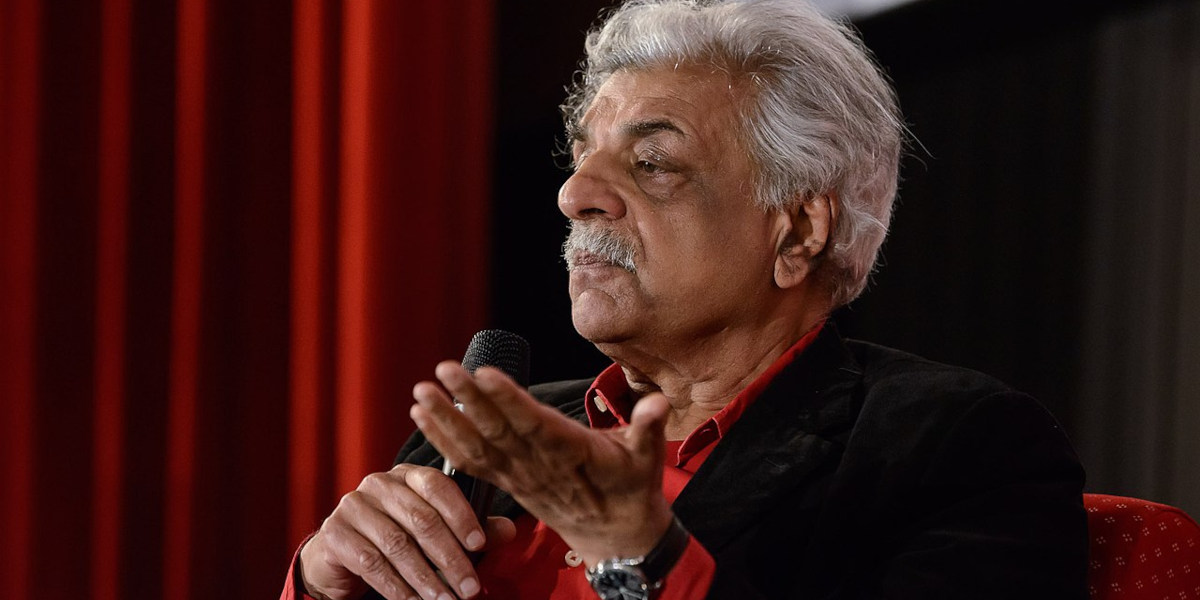

The first volume of Tariq Ali’s autobiography, Street Fighting Years (1987), focused on his youth. This latest volume follows on from 1979, taking the reader into his eighties, and includes a selection of his writings, headed with characteristic nonchalance as ‘JOTTINGS’.

Ali’s output has been prodigious – over fifty works are listed under the heading ‘By the Same Author’. He dedicates this memoir with Sphinx -like discretion to his partner, Susan Watkins, adding, ‘Our life together is also the time span of this book.’

Born in 1943 into a position of social privilege in Pakistan, Ali’s family were nonetheless politically progressive, thus opposition to imperialism and injustice were formative influences. As early as 1956 he was demonstrating against the Suez War; in 1957, along with other young rebels in many parts of the world, he was horrified by the news that a young American black man in Alabama, Jimmy Wilson, had been sentenced to death for stealing.

The following year, confined to bed with rheumatic fever, a teenaged Tariq read The Communist Manifesto along with the Just William novels by Richmal Crompton. After he organised a strike of underpaid Christian cleaners at the exclusive resort Nathiagali, his anxious parents insisted that he must leave Pakistan and apply for a degree at Oxford University.

Spirit of subversion

Admitted to Exeter College in 1963, he continued his interest in left politics, joining the Oxford Socialist Society and reading the Marxist historian Christopher Hill, whose work on the revolts of seventeenth-century Britain became a major influence. As a student Tariq’s name would become synonymous with the stirring of a new mood of dissent among the young intelligentsia.

Activism in the Vietnam Solidarity movement and a job as theatre critic on Town magazine followed. He met the literary agent Clive Goodwin, along with a creative group of leftists which included poet Christopher Logue, playwright Trevor Griffiths, critic Kenneth Tynan and filmmaker Ken Loach. He was also closely associated with the group of intellectuals around the New Left Review, including Perry Anderson and Robin Blackburn. In 1967 he helped to set up the Vietnam Solidarity Committee, which gained widespread support from newly radicalised young leftists.

In the following tumultuous year his interests continued to span literary and intellectual circles, while at the same time he maintained his active engagement in socialist politics. He was recruited by Ernest Mandel to the Trotskyist Fourth International, then, with Clive Goodwin, helped to launch the lively left paper Black Dwarf, which he edited. Irreverent, rebellious and eye-catching, it invoked the spirit of subversion which had moved early nineteenth-century radicals in Britain to resist oppression.

You Can’t Please All describes how Ali tackled a remarkable span of topics and themes in his writing, from Obama to Spinoza, from Lenin to Winston Churchill, from communism to Don Quixote

In 1974 he became the International Marxist Group’s candidate for Attercliffe, formerly the steel-making area of Sheffield in South Yorkshire. In the North of England, Tariq came into contact with militant trade unionists, supporting striking miners along with men and women on strike at Leicester’s Imperial Typewriters factory, many of whom were of South Asian origin.

From the 1970s, Ali wrote a series of books chronicling left politics, covering both his own participation and that of many others. They testify to a rich vein of thought and activism which subsequently became muffled as British society moved to the right. In the mid 1980s, he moved from print into television when he set up the Channel 4 current affairs show The Bandung File with Darcus Howe and Greg Lanning. Running from 1985 to 1989, The Bandung File specialised in investigative documentaries on neglected topics with a special relevance for Britain’s ethnic minorities.

From Obama to Spinoza

You Can’t Please All describes how Ali tackled a remarkable span of topics and themes in his writing, from Obama to Spinoza, from Lenin to Winston Churchill, from communism to Don Quixote. Alongside his commitment to radical journalism, Tariq has explored other forms of expression. His versatility as a communicator in many dimensions is truly remarkable. During the late 1980s, he embarked on imaginative playscripts such as Iranian Nights (1989). In the 1990s and 2000s he added novels like Shadows of the Pomegranate Tree (1992), The Book of Saladin (1998), and A Sultan in Palermo (2005). His range is extraordinary, moving from muck-raking exposures to Marxist theory; from boisterous satire to a sweet and gentle humour on his parents’ romantic elopement.

This is a fat book and a weighty book, yet a joy to read. I especially loved the section headed ‘A FAMILY INTERLUDE’, which includes a chapter on ‘The Noble and Warlike Khattars of Wah’ and an intriguing photograph, captioned: ‘My father (standing) with Sir Stafford Cripps in Lahore meeting young leftwing representatives to discuss the war, July 1942)’, which captures their apprehension and dread about what was to come.

I found myself returning again and again to another photograph. Taken in 1968, it is of a youthful, tender Tariq on a demonstration, holding John Foot, the son of Paul and Monica Foot, as a child in his arms. Momentarily it reveals the sensitivity and warmth that Tariq so carefully keeps from the world’s view, but which nevertheless permeate the pages of his second memoir.