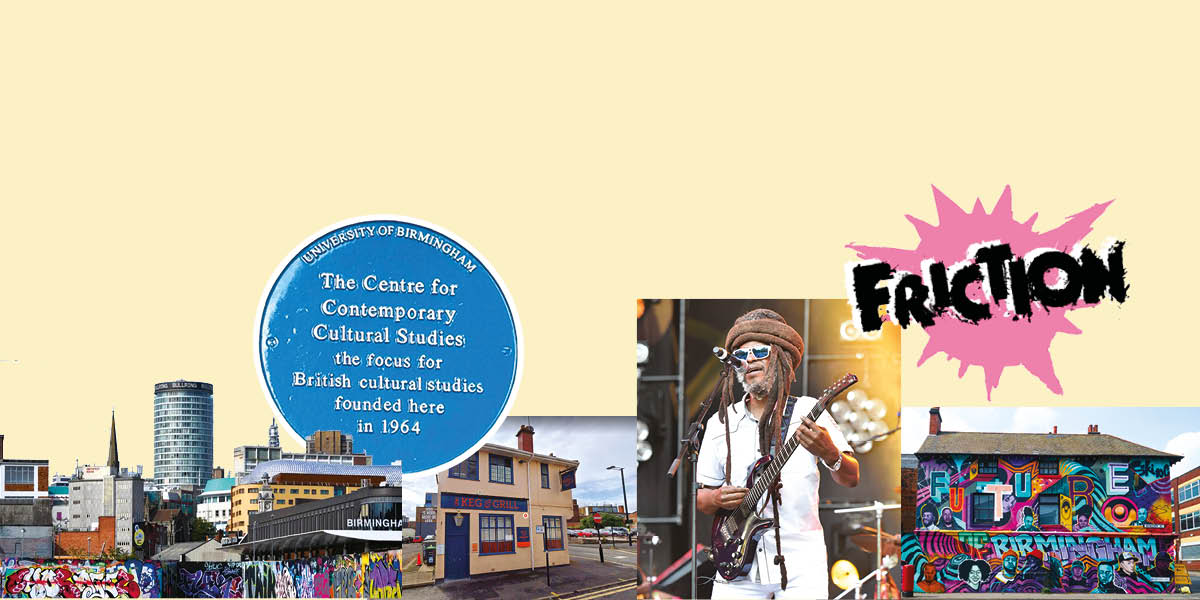

‘Birmingham is not the friendliest of cities,’ to quote Joel Lane, its great counter-cultural chronicler. An accurate, blunt assessment, typical of the directness that characterises long-time residents. With a huge dollop of sarcasm, Mark E Smith serenaded it as ‘the big heart of England’, a lyric referencing Birmingham’s sprawling, splodge-like footprint, its location just west of England’s geographical centre at Meridian Cross, and an old municipal marketing campaign. Birmingham is a generative cluster of over a hundred villages and a kaleidoscope of thousands of micro-scenes.

Radicalism is not necessarily the first thing you associate with the place. Despite being home to UB40, Steel Pulse, and Napalm Death – famed bands of 1980s deindustrialisation – it regularly returned a majority of Conservative MPs until the 1990s. Recently, Owen Hatherley used Ellen Meiksins Wood’s concept of the ‘pristine culture of capitalism’ to argue convincingly that Birmingham’s unplanned sprawl is among the purest distillations of the UK’s capitalist development.

It is truly a place of unworked out contradictions, difficult to navigate and pin down. Where you need not scratch too deep to expose a thick lode of bloody-minded radicalism marked by cussed individualism, tightly organised mutual aid and simple tolerance. Blunt, rough edged, and big hearted to the core.

Handsworth

In Georgian times, Matthew Boulton and James Watt established their steam engine factory in this north-west corner of Birmingham, upending the world of work and our climate system as they went. After 1945, Handsworth became a key destination for migrants from the Caribbean and South Asia.

Soho Road, among Birmingham’s most welcoming high streets, is home to many of the city’s oldest desi pubs, a true South Asian-British fusion. Migrants of colour establishing new lives and communities in England faced individual and structural racism. Their struggles forged the strong local branch of the Indian Workers’ Association – a history being researched by Professor Virinder Kalra of the University of Warwick, with plans to mount an exhibition this summer.

Handsworth has also been a key site for African Caribbean and black culture and creativity since the 1960s and 1970s. Some of Britain’s most important contemporary artists – Benjamin Zephaniah, Vanley Burke, Pogus Cesar – cut their teeth here. Its tradition of creativity and dissent remains in rude health. At Port Loop, just south of Winson Green beside the Birmingham Main Line Canal, grassroots organisations like Civic Square and MAIA Group’s YARD are maintaining and building radical structures and institutions that will enable ‘super-diverse’ 21st century Birmingham to thrive.

Digbeth

Still home to some of the small metal workshops upon which Birmingham was built, Digbeth is now primarily associated with creative industries. As in similar districts elsewhere worldwide, rising prices and property development is edging out its grassroots culture of raves, pop-up cinemas and independent street art, which thrived during the 2000s and 2010s.

Community arts pioneers Friction Arts, alternative central and eastern European cultural embassy Centrala and variegated cultural powerhouses Eastside Projects, Vivid Projects and Grand Union are among Digbeth’s creative community finding ways to battle on, facilitating one of the UK’s most exciting arts scenes.

Friends of the Earth Warehouse, in the shadow of Birmingham’s distinctive Selfridges, is a critical activist node that has been part of the city’s ecosystem since the early 1970s. It hosts Birmingham Trades Council, ACORN, and a plethora of other radical and environmental groups, as well as Voce Books, an independent bookshop with a packed events programme and a radical sensibility. A vacant space is currently seeking tenders for a new vegan or vegetarian cafe, to maintain a longstanding warehouse tradition. Out back, Digbeth Community Garden brings Birmingham’s rich tradition of community gardening into the heart of the city.

Moseley

Recently, Birmingham’s historic bohemian district has seen much of its alternative energy dissipated, priced out into adjacent Kings Heath, Selly Park and Stirchley. Yet, in its yoga studios, wholefood shops and rich tapestry of community spaces, Moseley retains something of the radical, alternative edge it developed in the 1960s and 1970s – when Kit de Waal, one of Birmingham’s best contemporary authors and a fierce advocate for working-class writers, was growing up.

Stuart Hall and many other CCCS researchers made it their home, bolstering Moseley’s reputation as ‘Birmingham’s Islington’. Today, the suburb is one where the divide between rich and poor is most blatant. Yet Moseley remains a hub for social justice campaigns and is at the heart of Better Streets for Birmingham, a lively struggle to upend Birmingham’s deeply ingrained and dangerous car culture. Nowhere else in the city are you more likely to be asked to sign a petition.

Stirchley

Now almost painfully fashionable, Stirchley was sucked into the city’s sprawl at the start of the 20th century. Early development was patterned by the Ten Acres and Stirchley Co-operative Society. Workers making the suburb their home developed co-operative shops, banking, sports, social clubs, even a funeral home, as Stirchley sprung up along the railway lines.

Now, as rents and property prices in the district soar, three modern co-ops – Loaf bakery, Artefact arts centre and the Birmingham Bike Foundry repair workshop – have banded together to construct a shared high street building. The mutually owned development will house all three, and provide nearly 40 affordable cooperative-owned and managed flats. Renovating Stirchley’s tradition of mutual ownership will play a key role in keeping alive its independent shops, artist studios and guerrilla community gardening projects.