Thelma Walker: The English question

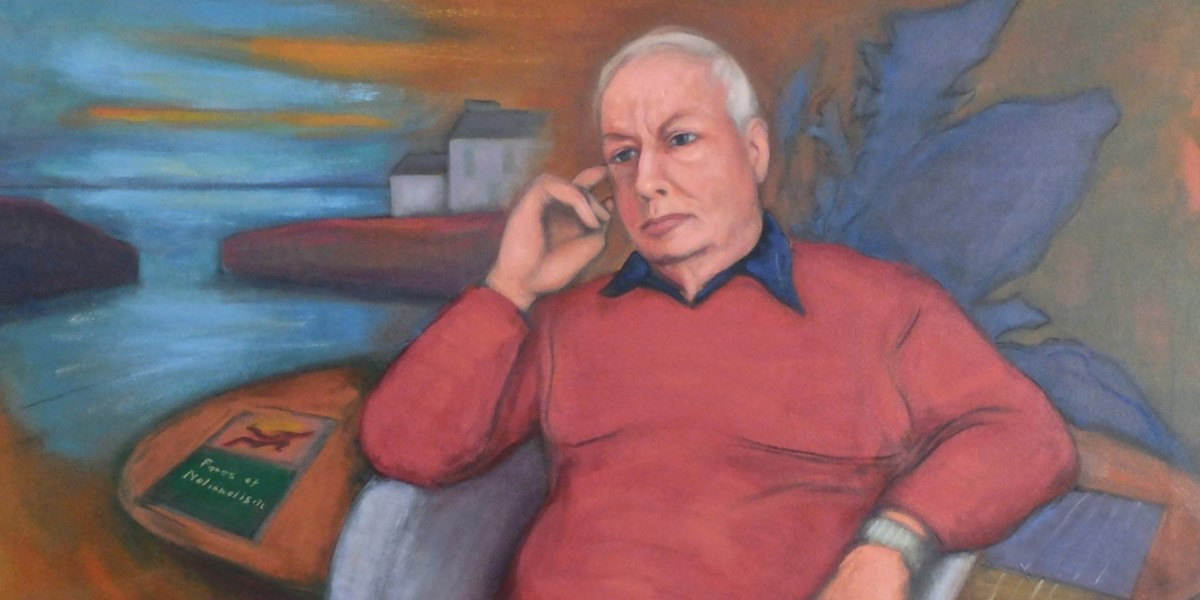

Tom Nairn’s The Breakup of Britain, recently republished at the height of the Brexit debate, made it clear to me that the deep, underlying issues within British politics and the question of the monarchy are still not being addressed.

In particular, Nairn helped me fully to consider the possible future for English politics if England were left clinging to the relics of the British empire in splendid isolation. What if, as Nairn propounds, Scottish and Welsh independence were achieved, along with Irish unification? What would the English political landscape look like?

Nairn spoke of, ‘a generation that overwhelmingly supports liberation from Downing Street’. I believe he was right; we definitely need to wrench political control from Westminster and build an alternative.

Pat Kane: Civic nationalism

Tom Nairn’s greatest achievement for the movement for Scottish independence was probably to provide the intellectual underworking for a shift towards civic nationalism, away from ethnic nationalism.

Nairn’s influence was evident in the specifics of the franchise in the 2014 independence referendum. The right to vote was based on duration of residence, and consistent fiscal contribution, not any conception of ‘roots’ or ‘race’. The hard-working, patriotic Scottish Pole or Syrian had a right to vote over any ‘authentic’ Scot scattered across the diaspora. Civic, not ethnic.

Nairn demonstrated how the nationalist process was a response to capitalism’s uneven development. This enabled the people of ‘the peripheries’ to exercise collective self-determination, based on how well they ‘imagined their community’.

The grandeur of Nairn also comes from his leftist cosmopolitan commitments, and the way he drew on them to build a model for ‘nationality politics’ in Scotland and beyond. We may know of the Tom Nairn-Perry Anderson thesis: it explains the ‘glamour of backwardness’ in British-state politics as an outcome of the compromised revolution of 1688, by comparison with European vigour.

Tom’s experiences in Italy, France and central Europe provided him with a template of the European ‘good life’: a place where art, politics and conviviality merged. Until the end, he thought that was possible not just for Scotland but for the English too, liberated from the post-imperial rictus of the British state. In the words of his most celebrated book, the ‘break-up’ of Britain would be a liberation for all.

Daniel G. Williams: The future of Wales

Unlike most commentators on Scottish nationalism, Tom Nairn was also interested in Wales. He noted the civic nature of Scottish nationalism with its focus on the state, and the more culturalist form that neo-nationalism took in Wales. He made a lacerating attack on theories of ‘cultural colonialism’, which lumped ‘too many different things together’.

Nairn identified two ‘types of nationalist dilemma in western Europe’: the under-development of pillaged regions and the over-development of epicentres of industrialisation. Scotland was an over-developed nation, with its nationalism focused on statehood. Wales, argued Nairn, ‘does not belong neatly’ to either category, sharing many of the features of forced rural under-development while also being a ‘great secondary centre of the European industrial revolution’.

If Welsh nationalism could ‘arrive at a political integration’ of the nation’s ‘contending’ civic and ethno-linguistic elements, then there was hope for others too.

Nairn concluded that because of Wales’ unusual suspension ‘between the standard alternatives of European neo-nationalism’ its future trajectory was ‘likely to be far more influential in the long run’ for ‘its position could be symbolically depicted as dead centre’. Whether that future is ‘Welsh European’ or ‘West Britain’, he might yet be proven right on this as he was on so much else.

In his own words: from ‘Step backward, leap forward’ (Red Pepper, January 2014)

Writing on the eve of the Scottish independence referendum, Nairn highlighted how new forms of governance are being sought to counterbalance the hyper-empire of global capitalism. Scotland is developing its own resistance, he wrote, and England could follow suit:

In his Brief History of the Future, the political philosopher Jacques Attali suggests that ‘more than a hundred new nations could be born in this century’ in reaction to what he sees as the ‘shock wave’ of capitalist-led globalisation. Scotland is in the middle of his list, in between Catalonia and Kurdistan.

Attali argues that capitalism’s victory in the cold war has led to ‘l’hyperempire’, a definitively polycentric world where democracies have found no alternative to swimming with the capitalist tide, but as a result are compelled to find new ways of living with it. Hence novel modes of adaptation are required, to assert (or reassert) themselves against the triumph of faceless markets.

Originally, capitalism arose among early modern city states and smaller societies such as the Netherlands, Belgium, pre-imperial England, Scotland and south Wales. Their successors today will depend upon ‘hyper-democracy’ to ‘counter-balance’ the pressures of advancing globalisation – like the constraints of City finance-capital in Great Britain.

One difficulty was that the course of what one might call ‘first-round’ industrialisation initially demanded communities of a certain scale – societies smaller than the great empires of antiquity, yet large enough to foster adequate markets, working classes and urban conglomerations. Only there could anything like contemporary ‘economic’ living (something like England’s model) develop – and compete against one another through the rapids of the industrial revolution’s first wave. This explosion in turn favoured an aggressive, often war-like culture.

These nation states facilitating capitalist industrialisation gave meaning and a sort of equality to growing masses of people, but in their wake lay imperialism and world wars – and then, attempts at state-fostered development far removed from the ‘civil society’ originally promulgated in Scotland, in both eastern Europe and areas of the third world.

Nation states facilitating capitalist industrialisation gave meaning and equality to growing masses of people, but in their wake lay imperialism and world wars

Only after the cold war would such high-pressure strategies diminish in intensity. The ‘-isms’ have slackened at last, to become more a matter of choice and ambition: the recognition, rather than the enforced adoption, of variety and lifestyles. The British-Irish periphery now have some claim to represent the imagined communities of another, emergent generation, one that benefits from post-1989 alterations of climate and general outlook.

So the 2014 referendum vote could be a significant contribution to this incoming wave, more about the future than the past – a future reaching out beyond the archipelago. ‘Yes’ is about the conditions required for such advance, which can’t emerge from civil society alone. Scots invented ‘civil society’ in the 19th century as an alternative to the loss of statehood, but in the 21st century it is no longer sufficient.

The prolonged recession between 2008 and the present has underlined the need for new ways to tackle a ‘cosmopolitan’ capitalism no longer able to guarantee reasonable development. Of course, independence ‘by itself’ won’t generate miracles. But the point is, surely, that no society is any longer ‘on its own’ and will only be able to contribute to a broader ‘Common Weal’ with the means to act, experiment and be different. Independence was never a sufficient condition of societal success, but does it not remain a necessary condition of tolerable change and bearable identity?