Title: Amy Ashwood Garvey and the Future of Black Feminist Archives

Author: Nydia A. Swaby

Publisher: Lawrence Wishart

Year: 2024

Bravo to Nydia A Swaby for Amy Ashwood Garvey and the Future of Black Feminist Archives. Through archival documentation and imaginative reconstruction, Swaby delicately leads us through the story of early internationalist Amy Ashwood Garvey, highlighting her relationship with the Jamaican pan-African leader Marcus Garvey, her quest to remain free from the domestic burdens that often plague women’s lives and her political and socially engaged work, while inviting us to interrogate the nature of archival practice. As a poet and founder and keeper of Nottingham Black Archive, Swaby’s work in foregrounding Ashwood Garvey resonates with me both personally and professionally.

Swaby’s book brings us closer to Ashwood Garvey’s life and our understanding of her as a 20th-century independent black woman. The use of portraiture to share and illustrate Ashwood Garvey’s narrative lifts her from the pages and into our hearts. I found myself poring over the photographs, imagining how Ashwood Garvey must have felt wandering continents too. It serves, as Swaby points out, ‘as a powerful reminder of the untapped potential within our historical narratives’ and also of the power when black women speak for each other. This is so important because, like many black women in history, ‘Ashwood Garvey was often sidelined in the very movements she helped to build, particularly within male-dominated pan-African circles.’

Strolling through the four chapters, preceded by an introduction in which Swaby sets out her aim and hopes for writing a visual biography of Ashwood Garvey’s life, is an absorbing and immersive read which allows the reader to open ‘new avenues for understanding and celebrating black women’s contributions across different spheres’. I am impressed and deeply touched by Swaby’s thoughtful and passionate work which invites us to reconsider Ashwood Garvey’s life through a black feminist lens, rejecting the often slanted tropes that have long hindered and overshadowed black women’s progress. If the archive is bound in patriarchal privilege, then Amy Ashwood Garvey and the Future of Black Feminist Archives seeks to rupture this.

I am impressed and deeply touched by Swaby’s thoughtful and passionate work which invites us to reconsider Ashwood Garvey’s life through a black feminist lens

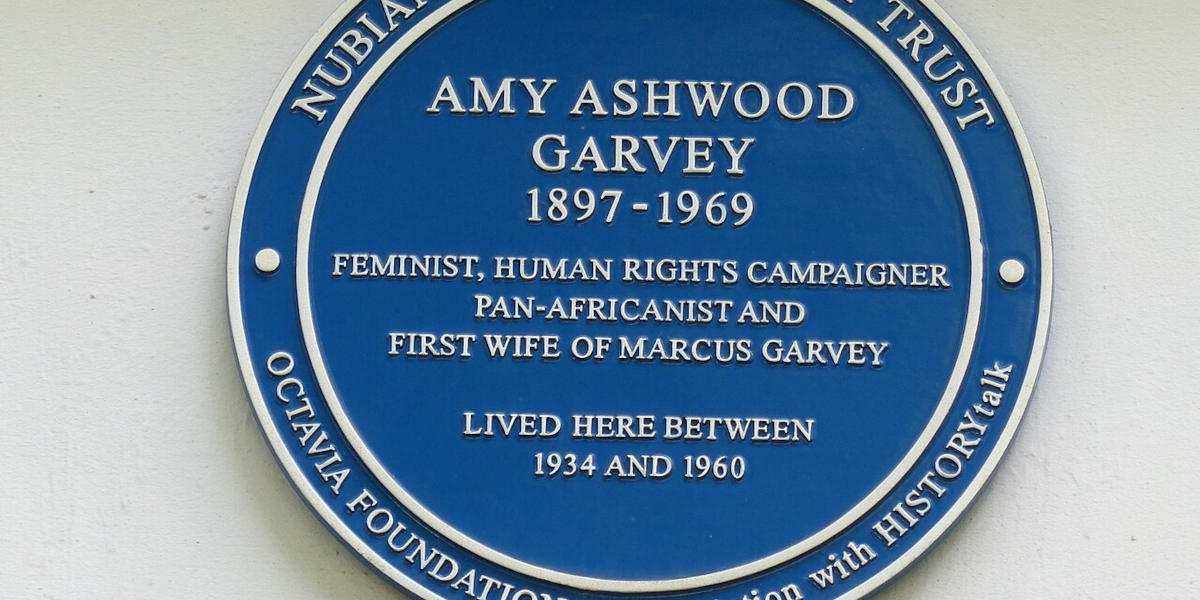

Swaby, with style, interrupts the discourse that often marginalises the efforts and contributions of black women and gives us more than a glimpse into Ashwood Garvey’s political and personal life as we are invited to also reflect on the future of black feminist archives and archival practice. Following the introduction, ‘Archival assemblages’, in which Swaby outlines her biographical and methodological approach, are four chapters that dig deeper into feminist archival practice and Ashwood Garvey’s life. The first, ‘Auto/biography as archival activism’, builds and expands on previous research. Chapter two, ‘The city as a living archive’, introduces us to the finds from Swaby’s ‘street strolling’ as she meanders through urban spaces, observing and interacting with the environment. At times I felt I was walking beside Swaby too.

Chapter three, ‘Towards a visual archive of diaspora’, digs ‘beyond surface impressions to uncover a deeper significance embedded within the visual narrative’. The final chapter, ‘The future of black feminist archives’, brings to light Ashwood Garvey’s efforts to ‘embrace a broader, more inclusive vision of solidarity, one based on shared histories of colonialism, displacement and struggle rather than just skin colour’, while also exploring the historical and contemporary contributions of women of African and Asian descent to social justice movements in Britain. Here we are introduced to practitioners such as artist Barby Asante and curator Aleema Grey among many as Swaby seeks to foreground other ‘sisters’ in the field to show ‘how the past informs the present and inspires future generations of black feminist thought and activism’.

Nydia A Swaby provides an opportunity for us to interrogate ‘the subtle undermining of black women’s contributions in academic and curatorial spaces’ and her intention to ensure that Ashwood Garvey’s ‘image and voice echo through the corridors of history’ is both admirable and necessary in a largely monocultural heritage sector. Amy Ashwood Garvey and the Future of Black Feminist Archive is a welcome and much needed contribution to the work that still needs to be done to make black histories visible in ways that can be understood and accessed by all. I found it a profoundly uplifting read and its worthwhile endeavour to elevate the voices of black women, who are often ignored and overlooked, critical. I highly recommend it as essential reading not only for those involved in archival practice, like myself, or for whom feminist research is a priority, but for all those who are interested in the power of multiple narratives.