Title: The Broken Promise of Infrastructure

Author: Dominic Davies

Publisher: Lawrence Wishart

Year: 2023

Dominic Davies urges readers to understand infrastructure as an emotion, a living organism affected by the broader socio-political dynamics. His book scrutinises the gap between the political promises of infrastructure improvements and the harsh reality of neglected needs and systemic failures, providing a nuanced analysis of the role infrastructure plays in shaping social and political landscapes.

Davies’ critique is rooted in the ‘infrastructures of feeling’, a concept derived from Raymond Williams’ structures of feeling, used here to argue that such projects manipulate emotions to create a veneer of progress while ignoring substantive issues. While the book covers case studies from South Africa to Silicon Valley, Stoke-on-Trent is its unlikely protagonist.

The failure of levelling up

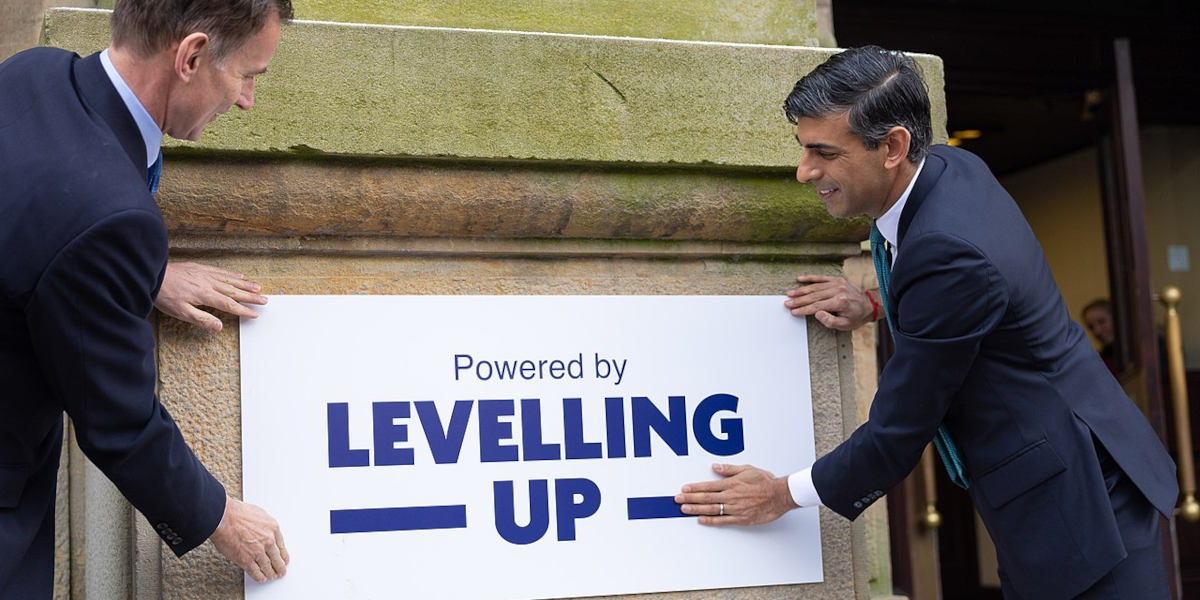

The book begins with a case study of the Conservative Party’s ‘levelling up’ agenda, a central promise of Boris Johnson’s government. Johnson promised significant infrastructure investments to address regional disparities, with the Etruscan Square development in Stoke-on-Trent as a notable example.

Funded by £20 million from the levelling up fund, the project includes a large arena, car park, and rental flats. However this development failed to address the city’s more pressing needs, such as social housing and effective public transport.

The book contextualises the evolution of the term ‘infrastructure’, tracing its origins from 19th-century France to its prominence in post-World War II discourse. Initially associated with public works, the term evolved to represent large-scale national projects and economic growth metrics. The shift from imperial to nation-state competition emphasised infrastructure as a measure of progress, with structural adjustment programs by the International Monetary Fund further tying developing countries to global capitalist economies over public welfare.

As the book further explores the historical and cultural narratives surrounding infrastructure, it reveals how political rhetoric exploits these narratives while neglecting genuine investment. The D-road in Stoke-on-Trent (so-named after it’s shape) provides a historical perspective, showcasing how this once-vital route supported mid-20th-century economic growth but now symbolises broader industrial decline. The D-Road’s decline, alongside the privatisation of public transport and the post-Beeching railway cuts, underscores the disconnection between infrastructure promises and the lived reality of affected communities.

The discussion then extends to how nationalist monuments in cities such as Stoke-on-Trent, Bristol and Paris obscure the collective labour, often from marginalised groups, that built the infrastructure underpinning these societies. For instance, the statue of Josiah Wedgwood outside Stoke station, erected in 1862, idealises his role in transforming North Staffordshire into an industrial hub, masking Wedgwood’s efforts to pacify unrest and involvement in colonial expansion reflecting Enlightenment-era beliefs in exploiting ‘wastelands’.

Davies’s broader examination also extends to Silicon Valley’s approach, where technological solutions often fail to address deeper issues of privatised transportation and public infrastructure. And while platforms like Uber and Deliveroo create the illusion of autonomy, these platforms shift costs and responsibilities onto individuals and private organisations, contributing to the degradation of public services.

Infrastructure and belonging

In addressing recent political issues, Davies questions former Stoke-on-Trent North MP Jonathan Gullis’s petition against housing asylum seekers in local hotels, highlighting how anti-migrant rhetoric can obscure broader infrastructural failures and perpetuate exclusion. The imagery of asylum seekers in hotels evokes fears of an ‘invasion’, drawing on historical prejudices about ‘dirt’ and ‘cleanliness’ and reflecting a deeper socio-political dynamic that distracts from systemic issues.

Davies also examines the historical and ongoing failures in British housing policies, emphasising two key broken promises: the first when the welfare state aimed to provide universal care, including safe housing; the second with the 1980s ‘right to buy’ scheme.

The book concludes by examining how belonging is tied to access to infrastructure such as safe housing and basic utilities. Through examples such as volunteer support centres for asylum seekers, Davies highlights the role of grassroots efforts in countering systemic neglect and violence. He reflects on the broader implications of infrastructure on freedom and belonging, concluding that infrastructure also holds the potential to foster inclusivity and justice.

The Broken Promise of Infrastructure offers a thought-provoking analysis of how infrastructure serves as a reflection of political and social priorities. It challenges readers to rethink the role of infrastructure in shaping societal values and to advocate for more equitable and sustainable solutions that address historical injustices and contemporary challenges.