Title: Twilight of the Soviet Union: Memoirs of a Moscow correspondent

Author: Kate Clark

Publisher: Bannister publications

Year: 2023

Twilight of the Soviet Union is a lively read – and something of a rarity. Many books have been written about the Soviet Union’s demise but few authors come at the subject from a socialist perspective and with regret that the experiment to combine state economic intervention with democratic politics did not succeed.

Clark went to Moscow in 1985 as a correspondent for the Morning Star. Mikhail Gorbachev was about to be selected as general secretary of the Soviet Communist Party and Clark watched with excitement as his reform programme – ‘more socialism, more democracy’ – began to develop. She and her Chilean husband had spent a year in Moscow in 1967/68 as graduate students and spoke fluent Russian.

In 1985, with three children in Soviet schools, she had good access to what parents and teachers and ordinary Soviet citizens were thinking. As a communist she also had an advantage over other British or ‘western’ reporters, who were required to live in apartment blocks reserved for foreigners. Clark, her husband and their three kids lived in a block where their neighbours were Russians. They were lucky to have a flat on the ninth floor with a commanding view of the Kremlin but it also suffered from humdrum problems.

Clark was struck by the way many of her neighbours looked careworn and sullen. She heard their complaints about shoddy consumer goods and queues for food. No wonder she was eager for change.

Perestroika’s failure

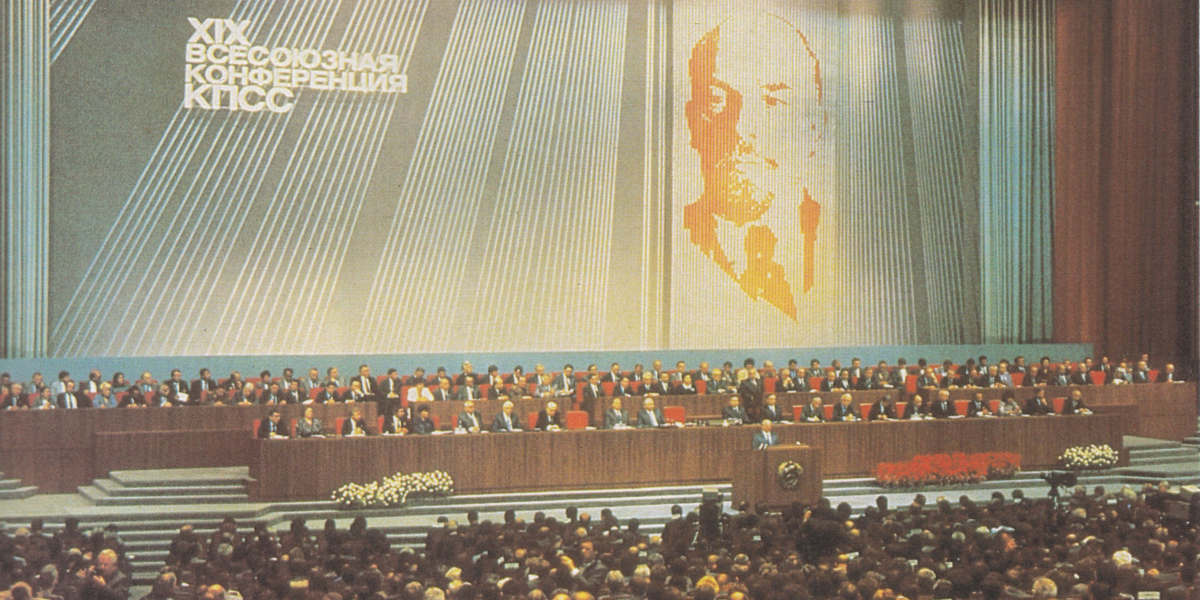

Her main job was to cover Gorbachev’s announcements of changes in the country’s political structures and the easing of censorship under the slogan of glasnost, or openness. She had contacts in the reformist wing of the Communist Party’s central committee who supported Gorbachev’s efforts to remove the dead wood. But she also found time to travel widely within the Soviet Union, visiting coal mines and factories to find out how his economic changes were impacting working practices. The aim was to give managers the right to make their own investment decisions instead of having to fulfil plans dictated from Moscow.

There are few other books on the Gorbachev era that give so much detail on the perestroika (literally ‘restructuring’) reforms, which were meant to change the way factories ran (through self-financing, cooperative and similar models), and how they mainly failed. Clark visited a remarkable number of factories to interview managers and trade unions.

She watched with alarm as nationalism spread through the 15 Soviet republics, turning politics into demands by local elites for ethnic supremacy. She saw how Boris Yeltsin changed from being a champion of democracy into an irresponsible populist with a destructive agenda and a vindictive desire to replace Gorbachev. While initially welcoming the breaking of long-standing taboos about Soviet problems that dominated the Soviet media under glasnost, Clark deplored the way Russian editors and journalists competed with each other in blackening almost every aspect of Soviet life.

She ends her book with a lucid summary of the various theories as to why Gorbachev’s reforms collapsed. One factor was the resistance of many factory managers to change, effectively sabotaging or blocking reforms. Other managers went in the opposite direction by privatising the profitable parts of their enterprises, keeping the proceeds and creating a new class of capitalists for themselves and their friends. They were helped by the dominant view among most of Russia’s academic economists that the only solution for the country’s problems was the fastest possible introduction of a market economy and the privatisation of all state enterprises.

Clark’s assignment in Moscow ended before Gorbachev was forced to resign and Yeltsin took full control. People’s savings collapsed overnight after Yeltsin gave a green light to a massive surge in inflation by ending price subsidies. Clark’s former Moscow neighbours were thrown into poverty.

An alternative portrayal

While Putin’s illegal invasion of Ukraine has led most of today’s western analysts to adopt a Reaganite portrayal of the Kremlin as the nerve centre of an evil empire, Clark argues that the Soviet Union was once a successful multicultural society with a democratic education system and opportunities for ethnic minorities. Contrast Kazakhstan with Afghanistan to see what Soviet power bequeathed. She points out that a large majority of Soviet citizens – with the exception of those in the Baltic republics, where the authorities organised a boycott – voted in March 1991 to keep the Soviet Union in existence. This was only nine months before Yeltsin and the leaders of Belarus and Ukraine declared the USSR was dead.

It is a sad story, which Clark tells well. No one in the 1990s predicted that Russia would return to the harsh authoritarianism that Putin embodies today. But hopes of a brighter future were already dimming when Clark left.