‘I have lived here for 57 years’, the British-Jamaican intellectual Stuart Hall told Tony Adams in an interview in 2007, ‘but I am no more English now than I ever was.’ He went on to describe an inner life, littered with the historical and unconscious debris of colonialism. ‘I am not a liberal Englishman like you,’ Stuart insisted. ‘In the back of my head are things that can’t be in the back of your head. That part of me comes from a plantation, when you owned me. I was brought up to understand you, I read your literature, I knew “Daffodils” off by heart before I knew the name of a Jamaican flower. You don’t lose that, it becomes stronger.’

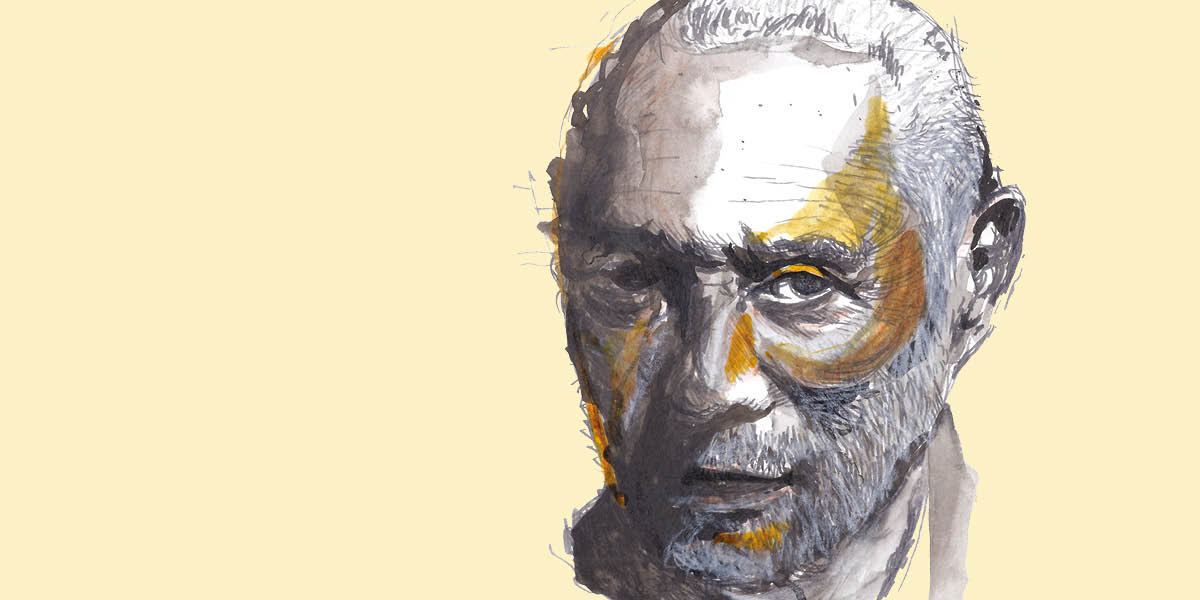

Born in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1932, exile in its various colours weaves its way throughout Stuart’s work. Those who studied with him, or have come across his work, will well appreciate how exile for him could be painful and come with a capacity for play and improvisation, cutting through orthodoxies, much like the modern jazz that he loved. ‘I knew that it was a world from the margins,’ Stuart said in his Desert Island Discs interview when introducing the music of Miles Davis. ‘It opened up the possibility of really experiencing modern life to the full, and it formed in me the aspiration to go and get it, wherever it was.’

At times like this, as the world is witnessing the deadly overlapping convulsions of capitalism, colonialism and racism, most recently in Gaza – possibly the most audio-visual of genocides – the arrogant complicities of our politicians and public institutions are in full view. With so much cultural gaslighting going on – genocide is not genocide; rallies for peace are rebranded ‘hate marches’ – the absence of Stuart’s imagination and cultural critique feels even more palpable.

Stuart was agile in slipping across the borders of the university, arts and activism, between images, sounds and writing, the local and the global

Yasmin’s earliest memories of Stuart are his 1980s Open University TV appearances. There were few black and Asian people on our screens then, apart from offensive caricatures, passed off as comedy – a genre Stuart skewered brilliantly in ‘It ain’t half racist, mum’ (1979) for the BBC 2 Open Door series. Yasmin would go on to study and then teach his work, meeting him sometimes at social and academic gatherings. Teaching with Stuart’s academic texts is not always easy. But show clips of him talking and most students, even those hiding in the back row, are rapt.

Described as ‘the Du Bois of Britain’ by Henry Louis Gates Jr, Stuart was an eloquent, forceful critic of the continually evolving faces of injustice, including their masking. Using the conceptual equipment of Marxism, post-structuralism and psychoanalysis, he showed how the everyday languages of the media, as well as national policies, bustle with desire, repression, projection and ambivalence. These intellectual coordinates, as well as Stuart’s reputation for being a good pianist, drew him into the orbit of those such as the exiled Palestinian scholar Edward Said, another skilled pianist, whose voice is also keenly missed at this time.

A permanent record

Both Stuart and Edward took part in what Mike Dibb has called his ‘long conversations’. These were films Mike produced as permanently accessible records of the charismatic thinkers he admired – who also happened to be brilliant communicators, able to translate their ideas into a conversational form, thus engaging those who may never get around to reading their work.

When Yasmin and Mike first met, around 2016, in projects to mark the 90th birthday of John Berger, it was Mike’s film of a conversation between Stuart and C.L.R James that was a talking point. The content is completely riveting, but so too is Stuart’s attention and skill as a discussant. His whole body listens, ever so intently, enabling him to coax the most wonderful stories and memories from James.

This conversation – filmed in the room in Brixton where C.L.R was then living above the offices of the Race Today collective – was a rerun of a wonderfully free-ranging BBC studio-based conversation that Mike had recorded almost ten years earlier. That had been planned as an additional programme to Beyond a Boundary, the film Mike was then making with C.L.R about cricket. Outrageously, the original recording was rejected (probably unseen?) by the then controller of BBC2 as being ‘of no interest’ and as a consequence was subsequently wiped – something that still makes us wince.

Mike first came to know of Stuart through The Popular Arts, a co-written book with Paddy Whannel, first published in 1964, when Stuart and Paddy were teachers in London secondary schools. The book is an early example of their shared talent in melting the gulf between popular culture and high art, a skill Stuart continued to use throughout his varied career.

Attentive dialogue

For us, there is no better way of experiencing Stuart’s gifts as a thinker and communicator than watching and listening to him in dialogue with others. There is the engaging smile, twinkling eyes and obvious eagerness to share his search to find just the right words for what he wants to say. All of this comes alive in a five-minute conversation between Stuart and the American-British writer and broadcaster Bonnie Greer, which was a highlight of Reflecting Skin, the 2005 film Mike made with her about black people in western art. Stuart, filmed in his home, proudly shows Bonnie the Phaidon collection Different, curated and written with curator Mark Sealy.

Different is a lush, vibrant and sexually ambivalent catalogue of the work of diasporic black and brown artists such as Albert Chong, Sunil Gupta, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Donald Rodney, Robert Taylor and Ajamu Ikwe Tyekimba. For Stuart, the images were laboratories. ‘You can be black in a thousand different ways,’ Stuart tells Bonnie. Blackness in the hands, eyes and bodies of these artists was not a reduction to one thing. ‘You can be black politically, stylistically and sexually.’ The collection for Stuart was more about raising questions than coming up with answers. ‘What they say is that we don’t really know what black will become.’

Leaving signification unfinished and as a becoming was another of Stuart’s gifts. It is how he undid lazy stories of identity, encouraging us to hold the tension between identities as being both ‘necessary’ (for political mobilisation) and ‘impossible’ (because they can never fully capture the turbulence and surprises of what we are and might become). It is often the case that the self-consciously diasporic can find some shelter in the no-man’s land of the in-between and not-yet.

These tensions and questions of who and what we are, and also what we might become, remain vividly relevant. Though sadly now without Stuart to help us respond to them.