In 2022, I made a video essay about neocolonialism in games. I opened by reflecting on my own childhood as a Muslim growing up in Britain in the 2000s, playing video games. As we all know, for Muslims or Arabs, noughties pop culture was saturated with dehumanising images of people like you, maybe your sister or your mother, almost certainly your brother or your father. Since October 7, 2023, it’s been hard to fight the feeling that little has changed. Few lessons have been learnt from listening to stories like mine for the last 20 years.

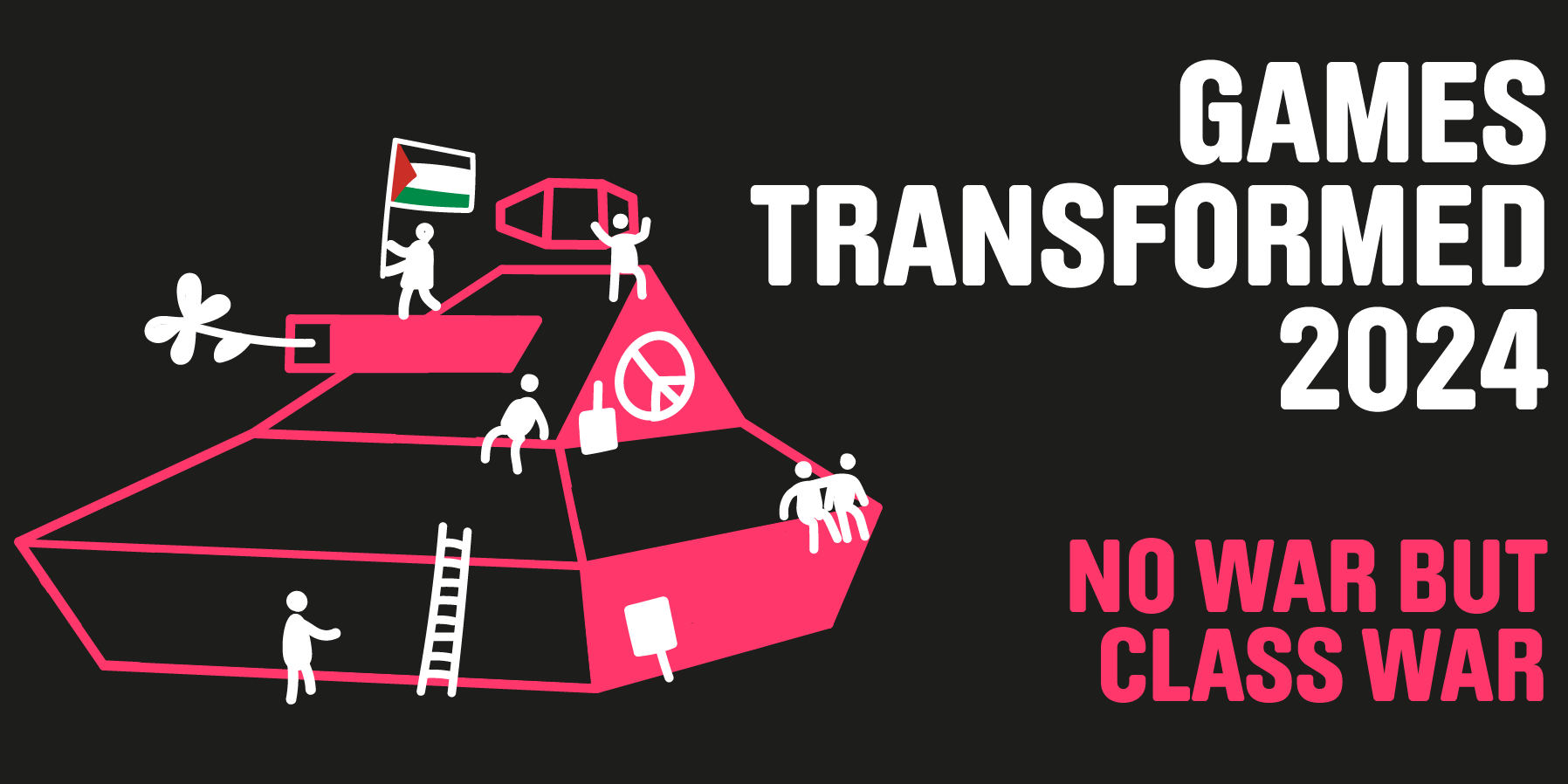

Games Transformed – a one-day festival and offshoot of The World Transformed – arrives amid this feeling. Dedicated to celebrating games and radical politics, it also arrives at an important time for the games industry. In the context of mass layoffs of workers, an increasingly hostile environment towards marginalised people, and a deadly silence on the genocide in Gaza, the opportunity to build community with politically like-minded people is more urgent than ever.

Workshops on trade union organising and talks about demilitarisation are built into a programme that also provides time for chatting over tabletop and video games. The festival marries community-building, upskilling and organising together with games in just the way I’ve been dreaming of – including through its game jam.

Jamming militarism

The festival’s game jam has been running since June 1. It asked teams to develop an ‘anti-recruitment’ game in response to the military’s increasing efforts to recruit gamers. It offers an opportunity to flex creative muscles and use existing tools to subvert expectations and creatively counter military recruitment. A game might change someone’s mind about joining the army, or empower resistance to imperialist wars.

At the festival, teams will present their ‘No War But Class War’ efforts. The best two games will be put into a custom arcade cabinet or made into a high quality tabletop game – and will be revealed at a direct action targeting the British Army’s recruitment drive. But in order to challenge the military’s use of gaming, we must first ask: why is the military targeting gamers?

The military-entertainment complex

The term ‘military-entertainment complex’ conceptualises the material relations between the military, political systems, financial systems, and Big Entertainment, exemplified through Marvel flicks and their US military funding. Honing in on games, the picture is even more nefarious: the US military has been collaborating with games studios to create customised war games, operating doubly as civilian entertainment and military training simulators, since the 1980s.

Your Xbox controller is being used to operate military drones, with software mirroring Call of Duty: Modern Warfare. Your Intel CPU is fuelling Israel’s ongoing settler colonial genocide against the Palestinian people – who are calling on gamers to boycott the company. The US military is using Unity engine to program killing machines and its army officers are hanging out at eSports events, trying to recruit you.

Gamers are perfect candidates to sit behind a computer and press buttons that murder people represented as dots on a screen

Gamers have become perfect candidates to sit behind a computer screen and press the buttons that murder tens, hundreds, thousands of people, represented as mere dots on a screen. It’s a chilling extension of the armies’ global legacies of targeting vulnerable teenagers with recruitment campaigns.

Creative resistance

In resisting military tactics, game jams organise creativity to positive ends. In November, my collective Game Assist co-hosted the ‘Towards a free Palestine’ game jam. It asked folks to not only imagine a free Palestine, but to explore how exactly we get there by creating new games. The entry Land of Olives uses resource-management genre mechanics to rebuild a destroyed Palestinian village. RESIST RESIST RESIST lets players adopt modes of resistance used by Palestinians in the West Bank, from flag-bearing, to wall-tagging, to stone-throwing.

Making games about war and imperialism pulls gamers into an urgent cultural conversation. As Israel’s bombardment of Gaza and across Palestine continues, we must interrogate the dehumanisation of Muslims and Arabs in games. The interactive aspect of jams is key. It’s one thing to watch on – feeling your safety is assured through the death of the sacrificial ‘terrorist’ archetype. It’s another to be the killer yourself, every time you boot up blatant propaganda like Call of Duty, or even ‘reality-detached’ worlds like Halo, beloved-by-gays classics like Mass Effect, and self-critical anti-war titles like Metal Gear.

Changing the script

The idea that the player is the killer is explored in Spec Ops: The Line, perhaps one of the most famous anti-war games. Research shows that it profoundly affected players – predominantly white and male – who had not previously questioned the military shooter formula. Yet they valued the deeply un-fun experience of play because it drove them to question genre conventions and their own subconsciously held beliefs.

That’s great, and proves that games can be a useful tool in the politicisation of gamers. But famous anti-war texts also have a tendency to alienate Muslim or Arab players like me by focusing on how war causes white suffering – rather than truly giving humanity to the dehumanised. As I’ve argued before, Spec Ops reproduces the racism it critiques in classic Heart of Darkness fashion. Its legacy certainly leaves lessons to be learned.

Anti-imperialism is fun

Fun games can also have anti-imperialist potential. Spirit Island is a cooperative game where players collaborate to defend their island home from colonising invaders. In Umurangi Generation, players are a Maori courier in Tauranga Aotearoa (New Zealand) navigating a crisis. The game explores science fiction allegory and the very real political apparatus that suppresses Indigenous autonomy. The hope and joy that can be found in play, as well as community building and collective resistance, are vital.

In resisting military tactics, game jams organise creativity to positive ends

Games Transformed gets to the heart of the radical artistic and material potential of games – a medium which at its heart is about building worlds. It asks: virtually and physically, how do we build worlds free of war and colonisation?

While the Game Awards insist on neutrality in the face of genocide, we must make it clear that military recruiters aren’t welcome in our spaces. We can’t wait around for the revolution. We have to dream it, program it, organise it for ourselves. Who better to change the world than the people who build worlds for us to play in?

If that sounds good to you, join us on Saturday 22 June at Pelican House for Games Transformed.