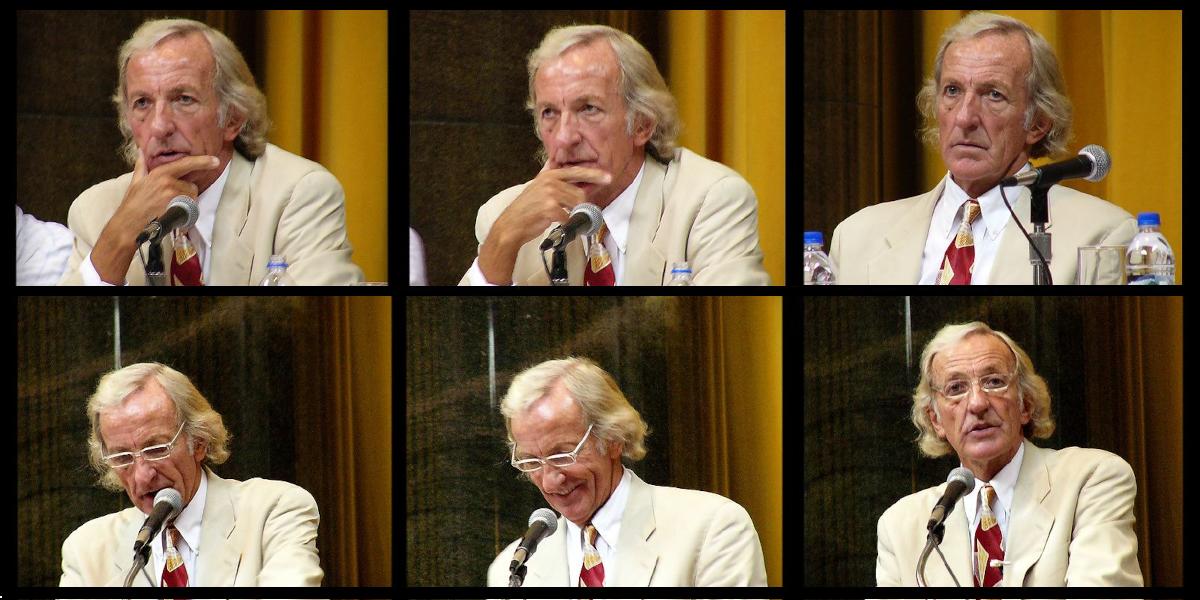

The award-winning campaigning journalist John Pilger, who died on 30 December at the age of 84, was renowned for giving a voice to people and causes ignored by the mainstream media and those in power. His uncompromising articles and television documentaries covered diverse issues including China, Palestine and American foreign policy and attacks on the National Health Service through increasing privatisation by successive governments.

Despite operating on the global stage and routinely interviewing world leaders and influencers, Pilger recognised a kindred spirit in the efforts of Red Pepper and its forerunner Socialist Newspaper to speak truth to power, and we were honoured by his generous, consistent support.

One public endorsement was when he joined Professor Noam Chomsky and playwright Harold Pinter on the stage at a packed Almeida Theatre in Islington, north London, in May 1994 for a Red Pepper forum on ‘The New Cold War’. The huge crowd – outside as well as inside – the theatre was testament to the pulling power of the three great left-wing thinkers – and this was long before social media could be used to generate interest.

Pilger and his fellow panellists challenged popular notions that the fall of the Berlin Wall had heralded a new era of global peace and cooperation. They presciently agreed that former Communist Party apparatchiks and major Western corporations would be the victors of this New Cold War while the working classes in the East and West would face more exploitation.

Questioning liberal orthodoxy

Questioning liberal interpretations of current affairs was central to much of Pilger’s work. The opening quote on his website states: ‘It is not enough for journalists to see themselves as mere messengers without understanding the hidden agendas of the message and the myths that surround it.’

In typically pugilistic style, one of Pilger’s final articles, written on 30 April 2023, contrasts the ‘electric’ opposition of writers and journalists to the coming war in the 1930s with the current ‘silence filled by a consensus of propaganda’ as the USA and China draw closer to conflict. He is not afraid to take aim at the apparently doveish former United States president Barack Obama for expanding bombing and ‘special operations’ during his time in office ‘as no other president had done since the first Cold War’.

Writes Pilger: ‘According to a Council on Foreign Relations survey, in 2016 Obama dropped 26,171 bombs. That is 72 bombs every day. He bombed the poorest people and people of colour: in Afghanistan, Libya, Yemen, Somalia, Syria, Iraq, Pakistan.

‘Every Tuesday – reported the New York Times – he personally selected those who would be murdered by hellfire missiles fired from drones. Weddings, funerals, shepherds were attacked, along with those attempting to collect the body parts festooning the “terrorist target”.’

In print

Pilger was born and brought up in Australia, beginning his journalistic career at the age of 18 in newspapers as a copy boy with the Sydney Sun, later moving to the city’s Daily Telegraph, where he was a reporter, sportswriter and sub-editor. In the early 1960s he moved to Europe, initially as a freelance correspondent in Italy for a year, before settling in London where he worked for several news organisations.

He was recruited by the Daily Mirror in 1963 and rose through the ranks to chief foreign correspondent. He was a war correspondent in Vietnam, Cambodia, Bangladesh and Biafra and witnessed the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy in Los Angeles on 5 June 1968 during his presidential campaign. Pilger twice won Britain’s Journalist of the Year Award: in 1967 and 1979.

He was a founder of the left-wing News on Sunday tabloid and became its editor-in-chief in 1986 but it was not a happy experience. He disagreed with the ‘Sunday Sun’ approach of the editor, Keith Sutton (whom Pilger had originally helped to recruit), and clashed with the paper’s governing committees on decisions such as basing operations in Manchester. Pilger resigned before the first issue appeared on 27 April 1987. The newspaper closed in November the same year, raising questions about whether it may have been more successful under Pilger’s more inspirational, if confrontational, helm.

His most frequent print outlet for many years was the New Statesman, where he had a fortnightly column from 1991 to 2014. In 2018, Pilger said his ‘written journalism is no longer welcome’ in the mainstream and that ‘probably its last home’ was in the Guardian. His last column there was in November 2019.

In film

Documentary films were where Pilger gained most recognition, including awards in Britain and worldwide. Thalidomide: The Ninety-Eight We Forgot, his 1974 programme for ITV, helped win compensation for children who suffered birth defects when expectant mothers took the drug. He went on to have his own half-hour documentary series on ITV, which ran for five seasons from 1974 until 1977.

His first documentary was The Quiet Mutiny (1970), made during one of his visits to Vietnam. It was the first of more than 60 films, including Year Zero (1979), about the aftermath of the Pol Pot regime in Cambodia, and Death of a Nation: The Timor Conspiracy (1993). His many documentaries on indigenous Australians include The Secret Country (1985) and Utopia (2013).

Palestine Is Still the Issue (2002) described how a ‘historic injustice has been done to the Palestinian people, and until Israel’s illegal and brutal occupation ends, there will be no peace for anyone, Israelis included’. He said the responses of his interviewees ‘put the lie to the standard Zionist cry that any criticism of Israel is anti-semitic, a claim that insults all those Jewish people who reject the likes of Ariel Sharon acting in their name’.

The War on Democracy (2007) was his first film to be released in the cinema. In ‘an unremitting assault on American foreign policy since 1945’, according to Andrew Billen in the Times, the film explored the role of US interventions, overt and covert, in toppling a series of governments in Latin America, and placing ‘a succession of favourably disposed bullies in control of its Latino backyard’.

A recurring theme for Pilger was that mainstream journalism means corporate journalism, representing vested interests more than those of the public. In his documentary The War You Don’t See (2010), he accused the BBC of failing to cover the viewpoint of the civilians caught up in wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. He additionally pointed to the 48 documentaries on Ireland made for the BBC and ITV between 1959 and the late-1980s which were delayed or altered before transmission, or totally suppressed.

While taking an unashamedly left perspective, Pilger’s emphasis was always on using painstaking research and analysis to tell the stories we need to hear. In today’s fragmented media landscape, this has never been more important.