India’s Hindu nationalist (Hindutva) government, led by prime minister Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), seeks to define India as a Hindu nation using strategies of ‘saffronisation’. Saffronisation is a politicisation of ‘saffron’ – a colour considered sacred in Hinduism – through recontextualising the country’s history to suit Hindutva agenda and invoke pride for a muscular ‘Hinduness’.

Saffronisation entails cementing an upper-caste Hindu past and future while also edging out minorities – particularly Muslims, Christians and lower castes – culminating in open hostility and repeated public violence. The saffronisation of the public sphere is simultaneously brazen yet disguised, vague yet mainstreamed, confrontational yet normalised.

Hindutva pop artists are establishing an ardent fanbase based solely on spewing musical hatred against Muslims, disseminating genocidal arousal and engendering ‘violent spectating’ buttressed by the most malicious Hindutva themes.

More subtle forms of saffronisation exist in India’s massive cinema industry. Popular cinema is already profiteering from the identity politics of Hindutva – particularly by reifying binaries such as the ‘native’ Hindu valiant warrior versus the ‘foreign’ invading Muslim ‘barbarian’.

It also assembles a nostalgia for a mythical past, particularly through the theme of ‘Ram Rajya’ (Rama’s kingdom). An archetypal past-cum-future imaginary that has had many lives in India, Ram Rajya is the utopian rule of an upper-caste Hindu god – Ram/Rama, from the epic Ramayana – characterised by peace and prosperity.

Nostalgia in nationalism

Nostalgia is an often-underappreciated component in nationalism: a carefully crafted collective yearning for a lost idealised and often non-existent past, used in the service of contemporary political projects. The ‘glorious golden age’ serves to galvanise a particular form of collective social identity that stresses shared cultural heritage for a unified nation.

At the same time, nostalgic visions exclude those deemed internal and external ‘others’ responsible for the downfall of this golden age (the Mughal era is currently being removed from the Indian school syllabus).

This repurposing and ‘presenting’ of the past – a kind of heritage politics – not only mobilises support for political causes and commercial interests but also provides distraction from bad governance, through the promise and vision of a regenerated past-inspired future, associated with pride and dominance over enemies. Nostalgia, therefore, can be used to build hegemony by nationalist movements and parties, by articulating disparate individuals and groups into a nationalist political identity while marginalising others.

The notion of Ram Rajya was central to Mohandas (Mahatma) Gandhi’s utopian vision for India’s future, post British imperialism. In Gandhi’s ‘critical traditionalist’ nationalism, Ram Rajya was ‘true civilisation’ – ‘a perfect democracy’ free of social and economic inequality. Nonetheless, this vision sought to preserve the traditional, deeply hierarchical and patriarchal institution of caste.

Today, Ram Rajya – the utopian rule of an upper-caste Hindu god – is a fixture of a growing saffronised public culture that furthers the ruling BJP’s authoritarian politics

The nostalgia of Ram Rajya was later invoked in post-independence India by the Congress government of Rajiv Gandhi in the 1980s. Styling himself as a leader of technological and military prowess, Gandhi sought to shore up support for his flagging government by invoking national pride for the future he claimed he would deliver. In 1987, he made the momentous decision to broadcast a serialisation of the Ramayana on the national television broadcaster, which proved wildly popular, attracting an estimated 100 million viewers.

Gandhi’s supposedly technology-driven celebration of the Ram Rajya myth aimed to prefigure the future in the supposed scientific, military and economic successes of India’s glorious past. Yet the promotion of religion by government institutions had been, until then, frowned upon.

Ramjanmabhoomi, Ayodhya and Babri Mosque

The popularisation of the Ramayana and the Hinduisation of the public sphere by Congress opened new political opportunities for the Hindutva movement. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, they would saffronise the public sphere through the politics of nostalgia.

In 1989, the BJP-allied Hindutva organisations Vishwa Hindu Parishad and Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh launched the Ramjanmabhoomi (Rama’s birthplace) movement to agitate for the building of a Ram temple at the alleged site of Rama’s birthplace in the northern Indian town of Ayodhya, where the Babri mosque stood. In 1990, the BJP launched a rath yatra – a chariot procession meant to resemble those detailed in Hindu myths.

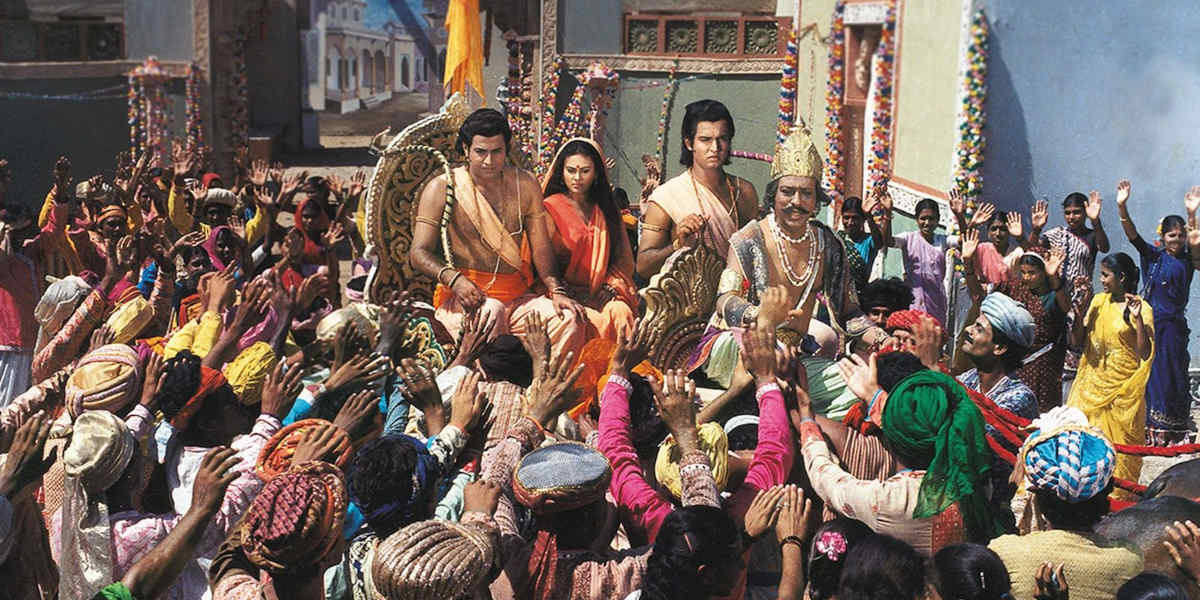

A still from the 1980s series Ramayan, showing Lord Ram with his brother Laxman and wife Sita

CREDIT: RAMANAND SAGAR PRODUCTIONS

Influenced by the series, rather than other known versions of the Ramayana, this Hindutva conglomerate transformed Rama, a god-king often portrayed as mild-mannered and of north Indian provenance, into a militant all-India icon for Hindus. Volunteers dressed as characters from the series: the BJP leader L K Advani even drove through northern India posing as Rama in a jeep converted to resemble a chariot.

The movement led to a campaign of communal violence, with more than 2,000 (mainly Muslims) being killed in 1992 and the Babri mosque being demolished.

Ram Rajya today

Today, Ram Rajya is a fixture of a growing saffronised public culture that furthers the ruling BJP’s authoritarian and anti-minority politics. Mainstream, overtly Hindu nationalist films have protagonists drawing analogies with the Hindu god Rama – invoking a saffron agenda with explicit support from Hindutva leaders, who equate these characterisations with a ‘cultural revival’ that would return the country to its ‘glory days’.

Others play with the imagery of Ram Rajya in much more innovative ways, combining a nostalgia for the glorious (Hindu) past – rebrand(ish)ing traditional religious symbols to elicit a pride and freedom of Hindu identity – with futuristic themes and technologies. For instance, Ram Setu pits a secular state colluding with a greedy corporate against an honest ‘scientific’ modern faith man who excavates traces of the existence of Lord Rama, à la Indiana Jones. The movie attempts to turn mythology into factual history to present the supposed grandeur of the Hindu past in rational terms and chastise those who do not accept this ‘fact’.

The globally-acclaimed action drama RRR, on the other hand, delicately saffronises the Indian freedom struggle against the British through a climactic mythologisation of the protagonist freedom fighter into a maximalist Rama figure. This supposedly benign version of Hindutva is characterised by acceptance of all kinds of people, yet foregrounds a hypermasculine, vigorous upper-caste Hindu pride and aggression. It envisions a Ram Rajya premised on hierarchical and predatory inclusion, with the Hindu warrior archetype and his dominance being explicitly upper caste in tone and patronising towards all other identities.

Later this year, Adipurush – a contemporary adaptation of Ramayana inspired by sci-fi western movies – is set to be released, ahead of the inauguration of a Ram temple in Ayodhya and the 2024 general election. Thirty years after the BJP elevated its influence on Indian politics through televised Hindu nostalgia, its dominance will likely be confirmed alongside the promise of Hindutva futurism.