To know capitalism is to experience horror. This remains as true now, in the early decades of the 21st century, when accumulation still depends on the twinned violence of expropriation and exploitation, as it was during Karl Marx’s time, following the enclosure of the commons, the consolidation of the factory system and imperial expansion into new territories.

Capitalism can loosely be described as widespread wage dependency combined with alienable property rights and production for profit in the market, all of which is geared towards accumulation through private gain. But that is much too anaemic a description. Modifying the old idea that money ‘comes into the world with a congenital bloodstain on one cheek’, for Marx and Marxists ‘capital comes dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt’.

We all know Marx loved the patently gothic imagery of vampires and werewolves, of spectres and gravediggers, but we should also emphasise that in his account capitalism is a particular kind of horror story: it is a disgusting tale of blood and gore and bodily carnage. For Marx, capital has a taste for human viscera, chewing its way through bodily gristle, and this, he wanted to show us, is what capital does on a truly apocalyptic scale.

‘Capital,’ Marx famously tells us, ‘is dead labour, that, vampire-like, only lives by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks. The time during which the labourer works, is the time during which the capitalist consumes the labour-power he has purchased of him.’ Under capitalism, production consumes living labour to create value-larded commodities, which are sold for more than the bearers of that labour were reimbursed, thus realising their surplus value in the monetary form of profit, which can finally be reinvested to engineer more and greater production processes.

But this kind of exploitation is not just a matter of short-changing dispossessed workers who own nothing but their labour. Market competition encourages the reduction of labour time to a minimum while simultaneously positing labour power as the sole source of value. With this structural determination, which encourages the destructive pressurisation of human labour by the acceleration and intensification of production processes, comes the crunching of bones, the rending of muscle, and the liquefaction of brains.

Capital, in this view, is a meatgrinder that crushes human lives into sellable commodities

We need only think of the deformations, injuries, and fatalities caused by strained working conditions at every level of capitalist industry, from neurological trauma through to heart attacks, right down to broken bones, amputated limbs and mass deaths. Outside of those instances, every minute and every hour spent in wage labour is another minute and another hour in which our bodies are wired to a vast machine that only lives by draining our life substances. Capital is indeed a kind of predatory vampirism.

Or, in an altogether more grotesque formulation, ‘Capital given in exchange for labour-power is converted into necessaries, by the consumption of which the muscles, nerves, bones and brains of existing labourers are reproduced and new labourers are begotten.’ Capital, in this view, is a meatgrinder that crushes human lives into sellable commodities.

Descriptions like this get to the very essence of life under capitalism. They remind us how bodies and brains are mutilated into commodities, and how commodities are in fact the mutilated substance of our fellow humans. Just about everything with which we interact, from the food we eat to the clothes we wear, not to mention our myriad technologies, has only come to exist through bone-crushing, limb-tearing and physically as well as socially and spiritually ruinous exploitation, usually taking place at some distance from the point of consumption. The consumption necessary to replenish one’s labour power, or to even survive, requires the ingesting of our fellow humans.

‘We may say that surplus value rests on a natural basis,’ Marx reminds those for whom this appears as anything other than horror, ‘but this is permissible only in the very general sense that there is no natural obstacle absolutely preventing one man from disburdening himself of the labour requisite for his own existence and burdening another with it, any more, for instance, than unconquerable natural obstacles prevent one man from eating the flesh of another.’

Ceaseless horror

That capital is synonymous with horror holds currency within socialist and communist thought. In 1916, approximately one year before the Russian revolution, Lenin reasoned for the unspeakable bloodbath that would almost certainly result from an armed insurrection. His justification for probable carnage reframed it as a revolutionary necessity, whose exceptional status would distinguish it from the violence inherent to the incumbent mode of production. ‘Capitalist society,’ he maintained, ‘is and has always been horror without end.’

What we might call the horror film’s political unconscious became a staple of the genre, modulating in response to the transformations of capitalism

History teaches us that Lenin and the Bolsheviks ultimately failed to dispose of their adversary’s undead corpse, which continued to stalk the earth post-1917, and so Lenin’s diagnosis has remained agonisingly true. Theodor Adorno later looked back on the culture Lenin once sought to annihilate: ‘If one were drafting an ontology in accordance with the basic state of facts, of the facts whose repetition makes their state invariant, such an ontology would be pure horror.’ Even though capitalism would continue to grow and mutate, to expand its reach and accelerate its internal processes, it would always do so in coherence with the diagnosis of ceaseless horror.

Today, as we live through a global pandemic that makes body horror an inescapable reality, it is worth remembering that the nightmarish virulence of Covid-19 owes its existence not only to the vampire’s animal associate, the bat, but also to the machinations of capital in the forms of industrial deforestation, concentrated urban poverty, worsened public health systems and a world trade system for which Wuhan is a global centre of commodity production.

Eat the rich

If a critical understanding of capitalism brings us face to face with horror, can horror, as a popular narrative genre, help us orient ourselves politically within capitalism?

Think of the most obnoxiously violent B-grade horror cinema, the kind of horror whose various iterations visually and narratively privilege the abject moment when human bodies are destroyed in an explosion of blood and guts, often to a booming synth score. This kind of filmmaking was popularised in the 1960s by the scuzzy exploitation films of Herschell Gordon Lewis and then fully commercialised in the 1970s by George A Romero’s zombie epics.

So many horror films of this sort seem to inhabit a world wherein the working poor are made to face off against the industrial and financial elite. Their narratives exploit and explode a social order structured around the antagonism between two irreconcilable classes, one of which works while the other accumulates the value of that work. The sheer delight in what only appears to be violence for its own sake is a way of narrating the everyday sufferings of the overworked, unemployed and disenfranchised. The carnage is also a way of imagining the most sadistic revenge possible, an insurgent barbarism that reacts punitively to generations upon generations of one-sided, top-down class warfare. Their violence is the insurrection in miniature: less the return of the repressed than a full-blooded revenge of the oppressed.

This first wave of popularity for this kind of filmmaking came at a time when the American economy, which had been in a state of boom since the second world war, was entering a major crisis. This crisis – caused by declining rates of profit from industrial manufacture and worsened by a global oil crisis and a series of protracted wars with socialist states – looms large in horror films from the period. That is what we see, for instance, in films such as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre from 1974. Here a slaughterhouse foreclosure and a petrol shortage combine to generate the conditions for scenes of cannibalism, which are variously punctuated by tableaux redolent of the ongoing war in Vietnam. This redolence is only strengthened by the film’s more recent remake, which backfills the narrative with a plot about enlisting to go fight the Viet Cong.

The director, Tobe Hooper, has always insisted that his film is a direct response to the social unrest of its historical context. ‘We were out of gas in the country at the time,’ he has recently said, ‘and it boiled up out of those times. It’s all true, the content of the film, actually. People were put out of jobs, they were out of gas at the gas station.’ So what we end up with is a horror film that is, at its heart, the story of unemployed abattoir workers applying the skills of their trade to the butchery of humans. Here class antagonism within capitalism coheres with Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s famous aphorism: ‘When the people shall have nothing more to eat, they will eat the rich.’

No such thing as society

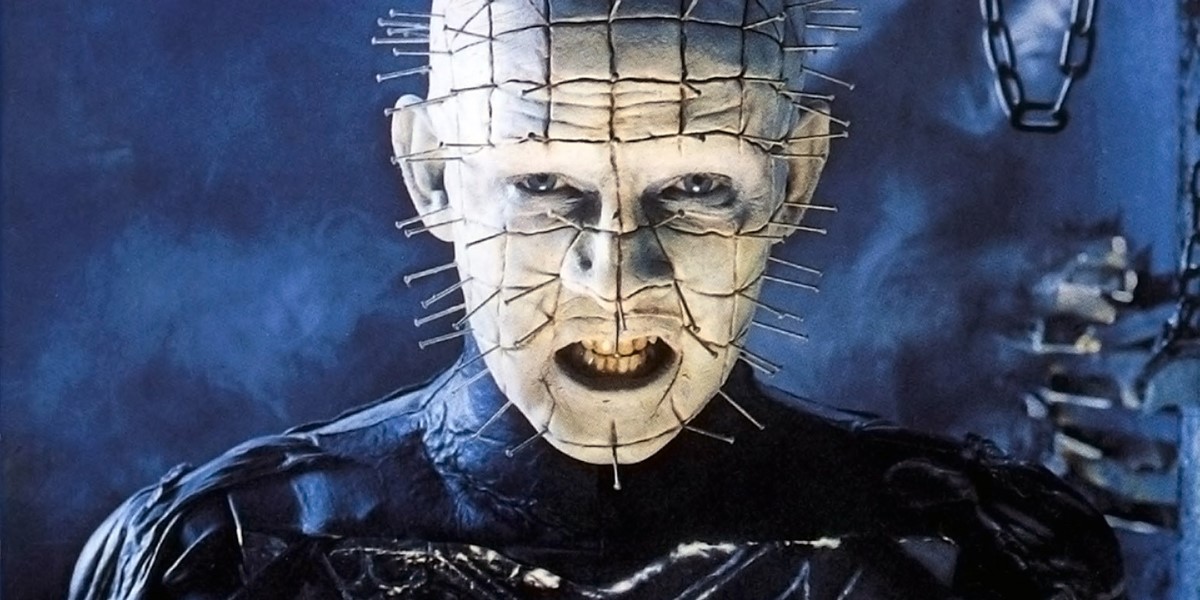

What we might call the horror film’s political unconscious became a staple of the genre, modulating in response to the transformations of capitalism. Against the economic and political policies of Reagan and Thatcher, with their elevation of the economic individual above anything social, the emergent aesthetic of body horror provides a bloody satire on the neoliberal ideals of a networked society and its individuated entrepreneurs. This is what takes place perhaps nowhere more horrifically than in Clive Barker’s Hellraiser, released in 1987, a film in which (to quote the iron law of Thatcherite property relations), ‘There’s no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and there are families.’

Hellraiser is a film that applies a demonic, soul-rending, face-shredding surcharge to property inheritance

The fact that this film contains no reference to history, and barely even glimpses an outside society, is in itself revealing of a social context. 1987 was the year in which Thatcher was elected for a third term as prime minister. Her political legacy – the economic sadism we know as austerity – was dependent on the very ethos that defined the new spirit of capitalism, forging ‘consent through the cultivation of a middle class that relished the joys of home ownership, private property, individualism, and the liberation of entrepreneurial opportunities.’

That is what we encounter in a film whose evidently wealthy characters all subscribe to Thatcherite ideology, whether they know it or not – and it is through that subscription that the individual men and women and their family are all sent to hell and back.

Hellraiser is, in more ways than one, a film that applies a demonic, soul-rending, face-shredding surcharge to property inheritance. Here is its radical subtext: provided one of the key steps toward communism is, according to Marx and Engels, the ‘abolition of all rights of inheritance’ by way of heavy, progressive taxation, that is what we are seeing written in a language of blood, drawn by flays and chains.

This kind of gross-out, ultra-violent horror has also enjoyed something of a renaissance in the 21st century, not least with the Hostel and Saw films grossing millions. But these new horror films, less exuberant and more melancholic than their predecessors, are not only responsive to the contradictions that gave us the

global recession but also to life in the new economy.

Much popular horror in the 21st century is responding to a historical moment wherein the flexibility and precariousness of labour find themselves allegorised by such gut-churning figures as the human centipede. ‘You have nothing to lose but your chains,’ goes the old communist adage. Maybe. But in the more recent waves of horror one film suggests that the only way to cast off the shackles is to saw through your own ankles.

Against this defeatism, perhaps we will do well to recall that the visual grammar of cinematic horror was first realised in the work of Sergei Eisenstein, communist cinema’s foremost practitioner and chief ideologue, for whom montage was described in the language of violence: ‘A throat is gripped, eyes bulge, a knife is brandished, the victim closes his eyes, blood is splattered on a wall, the victim falls to the floor, a hand wipes off the knife – each fragment is chosen to provoke’ associations.’

The purpose of horror to a filmmaker of Eisenstein’s calibre was to stir the spectator to a state of pity and terror, winning sympathy for the exploited and intensifying aggression against the exploiters. This is a tendency we are seeing renewed in much of today’s most popular horror cinema, in the films of Jordan Peele, Ari Aster, and Ben Wheatley, as well in franchises such as The Purge and Fear Street, where horror has once more become the visual form of social antagonism. To repeat the words of an urban guerrilla from Jean-Luc Godard’s most horrific film, a work of communist cinema directly indebted to Eisenstein: ‘The horror of the bourgeoisie can only be overcome by more horror.’