I joined Twitter in December 2010, at the height of the student fees protests. After a friend had some moderately incendiary tweets shared by a Guardian liveblog (or something like that), I wanted in on the action. As an undergraduate, my friends and I used to compete to get the stupidest letters printed in the student newspaper, and the Twitter game just seemed like an extension of that: winning would mean shouting something loud enough to catch the attention of the press.

At the time, there was a lot of talk about social media being some sort of new radical organisational tool – playing a role in the London riots, the student fees protests, the Arab Spring. On the timeline, new groups could form, come together, in the tweets and on the streets, and work towards the expulsion of the old. I remember images shared by the protest art collective Deterritorial Support Group (DSG) – who in hindsight were a bit like Led by Donkeys if they’d read a lot of French theory – bearing slogans like ‘The post political = The most political’ and ‘Strike! Occupy! Retweet!’ Twitter, in those days, almost seemed to promise something like the cinema audience that Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction optimistically spoke of: a democratic, self-regulating public sphere; a ‘matrix’ from which our old ‘customary behaviour’ might emerge ‘newborn’.

I remember Twitter feeling thrilling, intoxicating. What Patricia Lockwood called ‘the Portal’ in her 2021 novel No One Is Talking About This: a sort of endless rush of usernames, avatars; culture, politics, opinions; of new ways of thinking, new ways of being. A place where, to cite one Lockwood vignette, one might happen to meet a guy who has spent the past few years posting pictures of his ‘garage or kitchen or whatever’ with ‘increasing amounts’ of his own balls in the background, and then months later find oneself weighing up whether or not to leave one’s husband for him.

Say anything

In theory you could use Twitter to be anyone, say anything – so long as it remained within the character limit. Before it, social media was by and large anchored to the individual – to one’s concrete, indeed legal, identity. Under that Facebook model, one could of course say or comment on things, but always only as oneself, and for the most part to one’s immediate circle of friends.

Twitter was more like a web forum: perhaps specifically, it was more like SomethingAwful, a pay-to-post American forum from which the bulk of the ‘Weird Twitter’ users who defined the platform’s early comic style originally migrated. But whereas the old forums were essentially closed networks – inhabited, on a day-to-day basis, by a regular coterie of obsessives – Twitter was open, dynamic: a web forum that encompassed the entire globe.

At the time, there was a lot of talk about social media being some sort of new radical organisational tool – playing a role in the London riots, the student fees protests, the Arab Spring

Now that I think about it, when I joined Twitter in my early 20s, I barely even knew who I was. Far more than school or university or anywhere else, Twitter was where I learned how to write, how to think, how to talk about politics. It was also where I became used to drawing self-worth – from the dopamine rush of people sharing things I’d written, points I’d made. More than any actual, physical drug I’ve ever consumed, Twitter made me an addict. What would I even be without it? On Twitter, I met the mother of my children. It was effectively, for some years, via Twitter that I received the bulk of my income: I could support myself as a freelance writer via commissions that I got, contacts that I built up, through posting. And so, even when I wanted to break the habit, I very much materially couldn’t.

What little social mobility the media sector has seen in the past few decades has been driven primarily by Twitter. On Twitter one might start as nobody, and in a few short months post one’s way to a platform: the bulk of Novara Media’s stars, for instance, got their start on Twitter. Particularly in those early days, it felt like there was a great levelling effect: much was made of the fact that one could follow celebrities – but one could also publicly ‘own’ the pompous posters of the Labour right with quips and quote tweets.

Extreme takes

This is not, of course, to say that Twitter was meritocratic. The platform may have promoted a diverse range and profile of voices, but equally one of the surest ways to have one’s voice heard was by being as weird and belligerent as possible – to bait the crowd for hate-clicks. This tendency migrated from individual users to established news media conglomerates as well.

A great deal of culture was emancipated on Twitter – linguistically (note the influence of posters such as @dril, coiner of phrases including ‘corncobbing’ and ‘racism dial’) and politically (could the Corbyn movement have existed without it?). It could see great outpourings of joy, like the night it emerged that David Cameron had possibly fucked a pig. But equally, it was the website that gave us Jordan Peterson; that gave us TERFism; that gave us the political career of Donald Trump.

It is worth remembering that even before the Elon Musk takeover – and with that the various measures the billionaire tech bro has taken to promote his right-wing following – Twitter was hardly a godsend for the left. The problem was not just one of content and the double-edged nature of the forces it emancipated, but one of form. In retrospect, the platform’s entire logic was anathema to the formation of what we might think of as a ‘left-wing’ subjectivity’.

We might still mourn for Twitter, now that it has become ‘X’. Perhaps not for what it was, but for what it promised

Twitter might well have given plenty of individual leftists a platform for their views – but its logic was always, precisely, individualising, atomising. If Twitter ever managed to build consensus, it was usually through fear. Even the most anodyne reports of community-spiritedness, of basic niceness, might risk condemnation on Twitter – and not just from the right. Here, a woman who tweeted about cooking some chilli for her neighbours was held publicly responsible for everything from the failures of the feminist movement to the seemingly inevitable death of her neighbours from hypothetical food allergies.

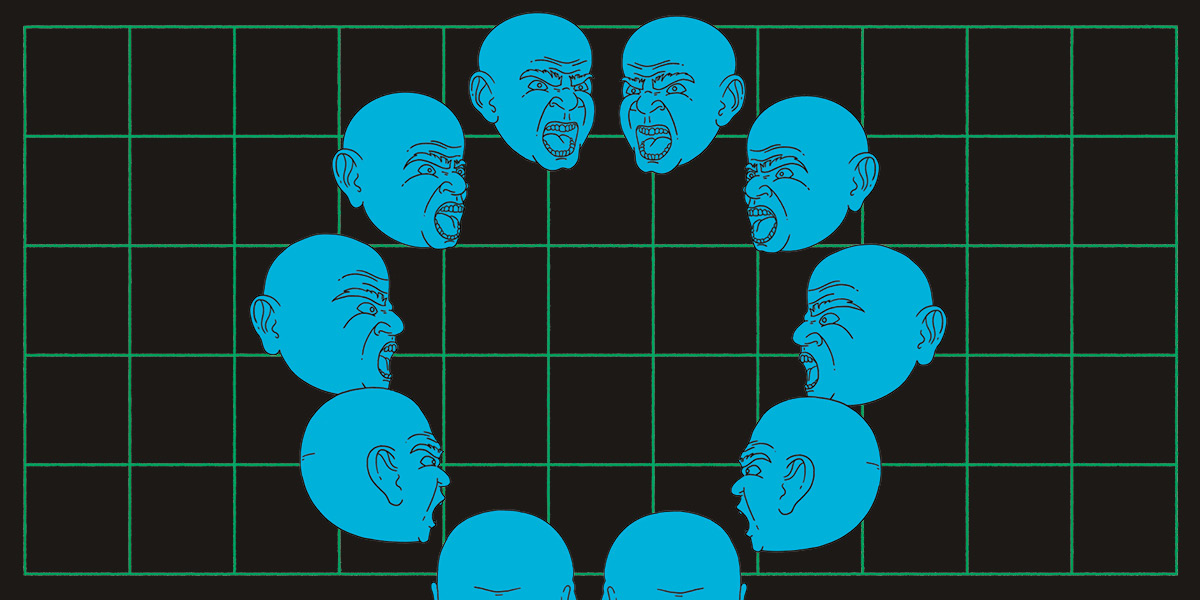

This audience was hardly Benjamin’s ideal public. Instead, the timeline more obviously resembled the crowd that Kierkegaard, in his 1846 essay ‘The age of revolution and the present age’, described as inhabiting his ‘reflective’, anti revolutionary ‘present age’: a divided but largely undistinguishable mob of would-be Roman emperors, hungry for entertainment and always eager to respond with disapproval. Never able to remember anything long enough to refrain from having the same, toxic debates again and again; never able to forget anything sufficiently to forgive.

To become a successful individual leftist, with a successful individual platform on Twitter, one would need to make navigating these atomising, accusatory forces into second nature. It became a place to become, as the cinema was for Theodor Adorno, ‘stupider and worse’.

Logging off

Like most old Twitter hands, I have long since moderated my usage. In a way, I even welcomed the Musk takeover, and the initial wave of f lounce-outs and chaos that ensued. For someone wired on the platform, in the way that I used to be, it was a bit like some warlord had announced they’d seized control of the world’s entire supply of heroin, and were now preparing to adulterate it to the extent that no-one could possibly use it to get high. ‘Thank God,’ I thought. ‘I don’t have to do this anymore.’

I do still use Twitter now and again, usually to procrastinate from work. I’ll admit it: I still enjoy the feeling that I might be writing something for the whole world to see, even as I know that the platform I’m speaking my thoughts to has long since been an ersatz version of itself. But I don’t really need that feeling anymore. Whatever gap Twitter used to be filling in my soul, it’s just not really there anymore. I’m no longer materially dependent on Twitter – and I’ve never been tempted by any of the alternatives.

We might still mourn for Twitter, now that it has become ‘X’. Perhaps not for what it was, but for what it promised: the open, democratic internet we might have had, if only the internet had ended up serving the interests of anyone other than venture capitalists. Instead, the internet only ever seems to get more centralised, to serve more and more the interests of the big tech companies (as well as the odd outsized big tech individual, like Musk) who own it. Twitter, perhaps, was never really ‘good’. But surely nothing better will ever replace it.