Undoubtedly, the climate crisis is intensifying. Extreme weather is taking hold, regularly impacting the lives of people across the planet with increasing intensity. Meanwhile, the UN climate conference – the global forum for the international community to tackle the problem – was most recently held in the UAE, one of the world’s largest oil producing states. The next iteration will be in Azerbaijan, an authoritarian petro-state. The irony is clear, and symbolic of the structural failure to mitigate climate breakdown.

In a context of flawed top-down decarbonisation and climate solutions, organised labour has an increasingly critical role to play in driving the shift towards a sustainable, low-carbon economy. We can, however, flip the script and explore worker-led decarbonisation initiatives. What if we ask: how can trade unions leverage their practical knowledge and collective power to reshape production? That is the only way to achieve a transition to a low-carbon economy that does not destroy the jobs, livelihoods and communities of large numbers of working people. Moreover, workers in high-carbon forms of production are often critically aware of its impact and interested in exploring how they can exert control over the purpose of their work.

In times of need

Unionised workers at the Broughton Airbus factory in North Wales demonstrated the potential of union-led industrial conversion at the height of the Covid pandemic in 2020, when the UK was faced with a seemingly dire shortage of ventilators for healthcare facilities. While much was made of Dyson and other corporates responding to then prime minister Boris Johnson’s call for economic actors to rise to the ‘ventilator challenge’, the key role of organised labour in its success received little fanfare.

Broughton’s Unite union branch had rapidly taken the initiative to repurpose the factory’s research and development facility to produce components for up to 15,000 ventilators for the NHS. Their successful response was coordinated by the union’s highly organised health and safety representatives. Despite misgivings from one of the UK’s specialist ventilator firms, the workers demonstrated how specialist skills and manufacturing production can be converted to meet urgent social needs.

This modern case of a worker-led initiative echoes the ‘Lucas Plan’ developed by the Lucas Aerospace shop stewards’ combine committee in the 1970s. Threatened by factory closures and job losses, it proposed an ‘alternative plan for socially useful production’, outlining around 150 medical, environmental and transportation products that could be manufactured to save jobs. The plan was ultimately rejected by management. However, it represented an early attempt at ‘transition bargaining’ – using collective bargaining to shift production towards social usefulness and public benefit rather than private profit.

By organising across and beyond workplaces, trade unions can unlock new possibilities for a just transition to a sustainable economy

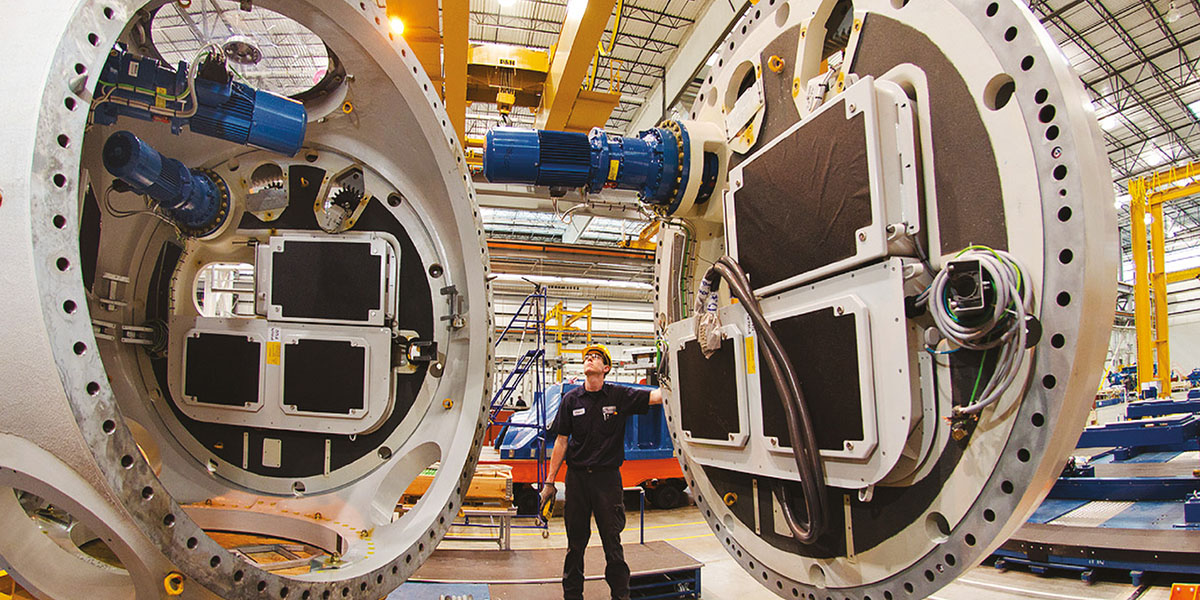

Rolls Royce aerospace workers recently took a similar approach. As redundancies loomed in the aftermath of the pandemic, union shop stewards built on their alliance with Coventry Green New Deal and increasing public awareness of the climate crisis. They took concerted industrial action against job losses while insisting the company explore low-carbon production alternatives, such as mechanisms for wind turbines. As with Lucas Aerospace, management resisted. However, in contrast to the 1970s, Rolls Royce shop stewards were able to secure a written agreement by leveraging the Rolls Royce brand’s vulnerability: the company needed to at least be seen to be reducing emissions. The agreement involved a commitment to exploring environmentally useful products if existing employment opportunities were to come to an end.

Whether in the 1970s or more recently, the potential transformative power of workers’ collective knowledge and practical skills provides inspiration and lessons for industrial conversion. By organising across workplaces, drawing on external contexts and support, and challenging management’s prerogative to unilaterally determine the purpose of production, trade unions can unlock new possibilities for a just transition to a sustainable economy.

Out of work

However, these examples also highlight obstacles to leading industrial conversion from the ground up. The decline of union power, globalisation of production and financialisation of capitalism have eroded workers’ industrial power. Austerity and the cost-of-living crisis have forced many unions to focus on defending jobs and livelihoods. Little capacity remains for broader transformation – though there are limited positive developments, such as Unite’s ‘Workers’ Plan for Port Talbot’ in the face of severe job losses.

To overcome these challenges, trade unionists are recognising the need to build alliances beyond the workplace. Initiatives such as the climate commissions in Yorkshire and Humberside and Scotland, are intending to link workplace-level efforts to broader strategies for a just transition. The TUC has also appointed staff across the UK to support worker-led transition.

Workers’ collective knowledge and practical skills can drive the transition to a low-carbon economy as actors with power, rather than purely as wage labour. As the Swedish author and associate professor of human ecology Andreas Malm has shown, the choice of fossil fuels over alternative energy sources was rooted in capitalists’ desire for greater control and exploitation of labour. Overcoming this dependency requires an actor with a vested interest and power in reducing emissions and the practical know-how to transform production – a role that organised labour is uniquely positioned to play.

Realising this potential, however, demands trade unions move beyond their traditional focus on exchange value (wages and working conditions) and engage with the use value and purpose of production. This, in turn, necessitates rethinking the relationship between workplace unionism and broader political and economic transformation.

Organised labour and campaigners for a low-carbon economy can look to the Preston model for inspiration. It is a real-life demonstration of the power and role of local government in shaping economic outcomes and building community wealth in the face of economic challenges and a corporate outsourcing status quo. The experiences of the Greater London Council in the 1980s also offer valuable lessons. Seeking to support worker-led alternative plans, the council’s London Industrial Strategy aimed to nurture organised labour and community organisations to transform production for public benefit.

Ultimately, overcoming the climate crisis requires a fundamental shift in the balance of power, both within production and in relation to the state. While the British state has historically been designed to protect the ruling order, the political establishment’s crumbling legitimacy creates new openings for movement-driven transformation. By building alliances that move beyond the workplace and developing practical alternatives, organised labour has the potential to extend the scope of collective bargaining.