Why did I leave the Labour Party after 40 years and move beyond my federalist, German-style vision of regional autonomy to become a member of the Northern Independence Party, whose vision is an independent Northumbria and a break from Westminster control of the north?

Reading Tom Nairn’s almost prophetic essays in the latest (fourth) publication of The Break-up of Britain (Verso) has helped me understand my recent political journey and believe in, as Anthony Barnett says in his new introduction, ‘the certainty of Scottish independence from Westminster, within a generation’. This has radical repercussions, including for the Labour Party. It sets in motion the wider dismantling of the British state, based as it is on a parliamentary monarchy and hence a parliament whose members’ primary loyalty – and therefore accountability – is not to the people but to the ‘queen in parliament’, placing parliament above the people.

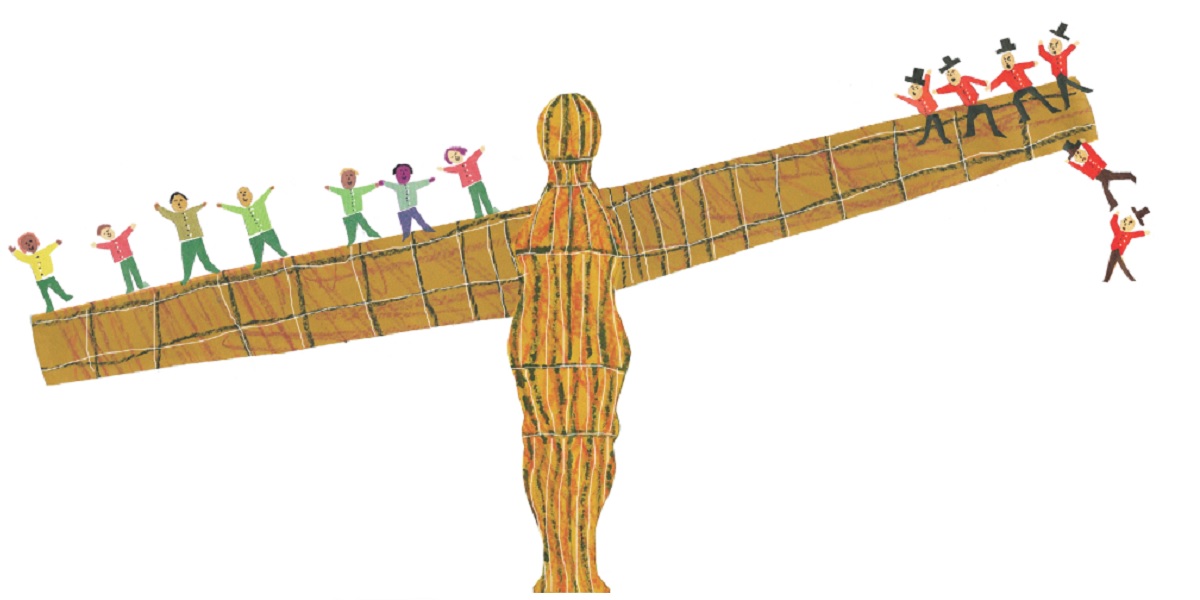

I see in Nairn’s work, first published in 1977, an impatience with the Westminster party political system, which ‘makes it next to impossible to obtain any new departure from within the system. The two-party equilibrium, with its antique, non-proportional elective method and its great bedrock of tacit agreement on central issues was formed to promote stability.’

This sums up why, after so many years of loyally supporting Labour as an activist, Labour MP and PPS to John McDonnell, I realise that with no electoral reform, no constitutional change, no open selection and forthcoming boundary reviews, the status quo will always be maintained in parliament with its weak accountability to the people.

As the Labour MP for Colne Valley from 2017 to 2019, I believe that Labour came closest under Jeremy Corbyn, with our democratic socialist policies, to achieving a socialist government, an end to inequality and the possibility of achieving a truly internationalist society.

It must be recognised, however, that the party did not effectively address the undemocratic nature of the British state, and lessons need to be learnt. This includes reflecting on the extent to which Jeremy Corbyn’s defeat is related to the threat his support for extra-parliamentary movements posed to the centralised nature of Westminster, ‘parliamentary democracy’ and the unaccountability of MPs.

Liberation from Downing Street

Having left the Labour Party, I began to reflect on how politics and parliament could be transformed. I began to consider the wider socialist movement and the many now politically homeless former Labour members. I engaged with, as Nairn put it, ‘a generation that overwhelmingly supports liberation from Downing Street’ and the leaders of new, emerging socialist parties. These include Alex Mays, leader of the Breakthrough Party, which recently stood its first candidate in Chesham and Amersham, and Philip Proudfoot, leader of the Northern Independence Party, which endorsed my candidacy in the recent Hartlepool by-election.

Both young men are inspirational socialists and leaders. My conversations with them helped me crystallise my thoughts and realise that without constitutional reform and the right to self-determination, social justice will never be achieved. I witnessed, first-hand, how the power and control of the parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) itself directly related to MPs’ inbuilt unaccountability to the people.

I know that some in the PLP were more comfortable working with Tories than those of us on the left. The next generation of political leaders are aware of the lost opportunity in 2017 and 2019, and are ready to fight for social justice and to consider the potential of a genuine left progressive alliance. Such an alliance would work for constitutional reform, including a referendum on northern independence.

Devolution is not enough. Nairn, in his 2003 postscript, said of Tony Blair: ‘Blair’s constitutional concessions and devolution was intended to continue, or even to strengthen the Union state and its crown.’

Blair’s devolved kingdom, while it gave a limited, frustrating taste of self-government that left many wanting more, is now seen as reinforcing its centralising mainspring, the unwritten constitution of Westminster and Britain’s lingering world-power pretensions. Devolution and the recent Tory introduction of the mayoral system is little more than enhanced local government, or as Philip Proudfoot describes it, ‘another layer of politicians making local people’s ability to influence change even more distant’.

There is criticism of the Northern Independence Party (and indeed the SNP and Plaid Cymru) that I want to answer: that fighting for an independent Northumbria/Scotland/Wales ignores the poverty and inequality that exists across our country; that the most important issues are class issues and we should be uniting on the left to fight for social justice everywhere, not just focusing on the north-south divide.

As a northerner, however, I have witnessed the ‘managed decline’ of northern towns and the empty promises of the ‘northern powerhouse’ for too long. The reality is that public transport is much cheaper and connectivity far better in London, education is far better funded and council tax in Westminster is far lower than in many of the most deprived northern towns. These factors, along with the belief by many northerners that their voices are not heard in Westminster, gives impetus to new and emerging parties.

Building meaningful democracy

In May 2021, I stood on the platform at Hartlepool leisure centre for the election results. As an independent candidate, endorsed by the then unregistered Northern Independence Party, I had to take it on the chin that I had lost my deposit and we were a world away from the 20,000-plus votes we won in 2017, when I was elected as the Labour MP for Colne Valley.

Even so, the NIP gained national recognition and in many ways that had been the goal. Northerners living all over the country are joining. Many have been forced to move out of their home region to seek secure employment. Many share a love of and sense of belonging in the north and are proud of their identity wherever they live. Above all, they reject centralised, unaccountable rule by Westminster.

The significant factor to be taken from Hartlepool and the two other recent by-elections, in Chesham and Amersham and Batley and Spen, is that between 40 and 50 per cent of the electorate chose not to vote and many of those who abstained were former Labour voters. There were 16 different candidates standing in Hartlepool and the low vote for the NIP reflected the split vote and the difficulty for any new party to establish itself. Are we seeing voter apathy or anger with Westminster politics? Either way, we need constitutional and electoral reform.

We can compare the low electoral support for new parties to the start of the journey for the SNP, which until the 1960s achieved little success. Then criticism of British control of Scottish affairs grew and North Sea oil raised the possibility of Scottish economic autonomy. We are now seeing a growing anger from the younger generation at the corruption and attacks on democracy from Westminster.

The demands of the NIP for an independent Northumbria may be a catalyst for a move towards an England of the future, if and when the other nations of the UK gain independence. An England that is itself independent of ‘Great Britain’ and unshackled from the British state.

Is this a transition period where we can challenge the nature of the British state and its political democracy? There has been a deference to Westminster for too long; we need a strategy for democratisation in each of the UK nations. The NIP’s demands can be part of that and the beginning of meaningful democracy.

Meaningful democracy includes economic democracy. True economic and social independence, community wealth-building, green, sustainable jobs and co-operatives – these were the popular policies in the Labour manifestos of 2017 and 2019.

There are, of course, good examples of strong, city-based initiatives in Preston and Manchester delivering such policies. The manifestos of the NIP and Breakthrough parties, however, are even more ambitious and address decentralisation and the specific regional needs of working-class people.

Organising against empire’s legacy

The next step, I believe, is for democratic socialists, of whatever party or none, to come together as a movement to ensure that voters do not just have a binary choice between Tories and Tory-lite Labour. There can be freedom from Westminster. Proportional representation is a precondition for that freedom and true democratic representation. Covid, climate change and years of Tory austerity have set the scene for the movement to deliver those much-needed socialist policies. A vital question now presents itself: what kind of an organisation is needed to lead this diverse and decentralised movement and challenge the ‘two-party equilibrium’, the Union and all that goes with it?

Tom Nairn speaks of the ‘legacy of the empire’. He describes ‘the governing, landed class and the history of a joint front formed by the landowners and the bourgeoisie against the proletariat back to the industrial revolution’. Little has changed when we have a Labour front bench who do not speak up for renters’ rights, and who vote with the government on human rights bills and the response to the Covid pandemic.

Labour today seems to be fulfilling Nairn’s observation that ‘stability and continuity could not be put at risk by rash or unnecessary reform’.Does my belief in the right to self-determination conflict with my socialist principles? Doesn’t nationalism conflict with internationalism? I believe not. Nicola Sturgeon articulated a response to these questions in 2012 when she said: ‘My conviction that Scotland should be independent stems from the principles, not of identity or nationality but of democracy and social justice.’

One accusation aimed at the NIP is that its aims are contradictory: regional autonomy and control yet internationalist. The EU, though based on serious inequalities of power, has shown that different states can work together on shared priorities while retaining clear and separate identities.

Parts of the north have a history of welcoming people from every nation while maintaining a strong regional identity. The stated aims in the NIP manifesto include: ‘To oppose all forms of ideology based on hatred and bigotry and to uphold the principles of democratic socialism and uplift the voices of our members.’

The NIP is truly inclusive, independent and socialist. It celebrates the history of the north as welcoming all people from all nations. It is proud of this identity while welcoming and embracing diversity. This is what makes it distinctly different from other regionalist parties like, for example, the Yorkshire Party.

An imperial state without an empire

There is a desire, I believe, across the UK for a break from Westminster and for self-government to ensure meaning, relevance and self-belief. With regard to Scottish independence, which will be the most decisive catalyst to this break, the very fact that Boris Johnson has intimated he will stall any opportunity for a further referendum, is justification in itself for every Scot to seek independence.

Labour lost 40 seats in Scotland in 2015, followed by many ‘red wall’ seats in 2019. The reasons for these losses are complex and varied but ultimately Labour has to face the fact that it has lost four consecutive elections and came closest to victory under Jeremy Corbyn in 2017.

Labour, as the polls show, is currently unable to connect with voters and it makes me sad to see its decline. A new, growing democratic socialist movement is emerging, however, and demanding a break from Westminster and our country’s colonial past.

The younger generation of voters is demanding electoral reform, constitutional change and a future where we are respected on the international stage. The Tories are clinging on to the remnants of the empire and trying to maintain control of a Union that is straining at the leash.

With the possibility of Scottish independence, followed by the Welsh, and the unification of Ireland, England could be left clinging to the relics of the empire in splendid isolation. For the north, this means continued centralised rule from Westminster without political democracy.

Now is the time to consider the serious possibility of the break-up of Britain and the nature of the British state. And that must include the democratisation of England. On this, the NIP is at least making a start, with its own challenge to Westminster.

Perhaps others will follow its lead, rising up against the way they too have been treated as subordinate provinces of an imperial state. I owe my personal thanks to Tom Nairn for helping me understand our history and how our nation’s future can be forged. This is about the right to self-determination and ultimately social justice and democracy.

Illustrations by Cressida Knapp