In August this year, Morara Kebaso, a 28-year-old Kenyan entrepreneur with a law degree, started an online campaign to expose all the infrastructure projects that President William Ruto had promised Kenyans but not delivered. Kebaso’s campaign started as a parody, mimicking the president by holding roadside rallies from the roof of his car, as Ruto often does. He then traversed the country using crowdfunded resources to see how many projects launched by the president had been completed. Kebaso discovered roads that had been allocated millions of shillings abandoned by contractors. One half-built stadium had goats grazing on the field.

Within no time Kebaso had gained a large following; ordinary Kenyans – fed up with skyrocketing corruption and rampant theft within government – began posting their own TikTok videos of stalled projects. They contributed generously to Kebaso’s campaigns, allowing him to purchase a new car with a sophisticated sound system. What started as comic relief morphed into a nationwide movement demanding accountability from the government.

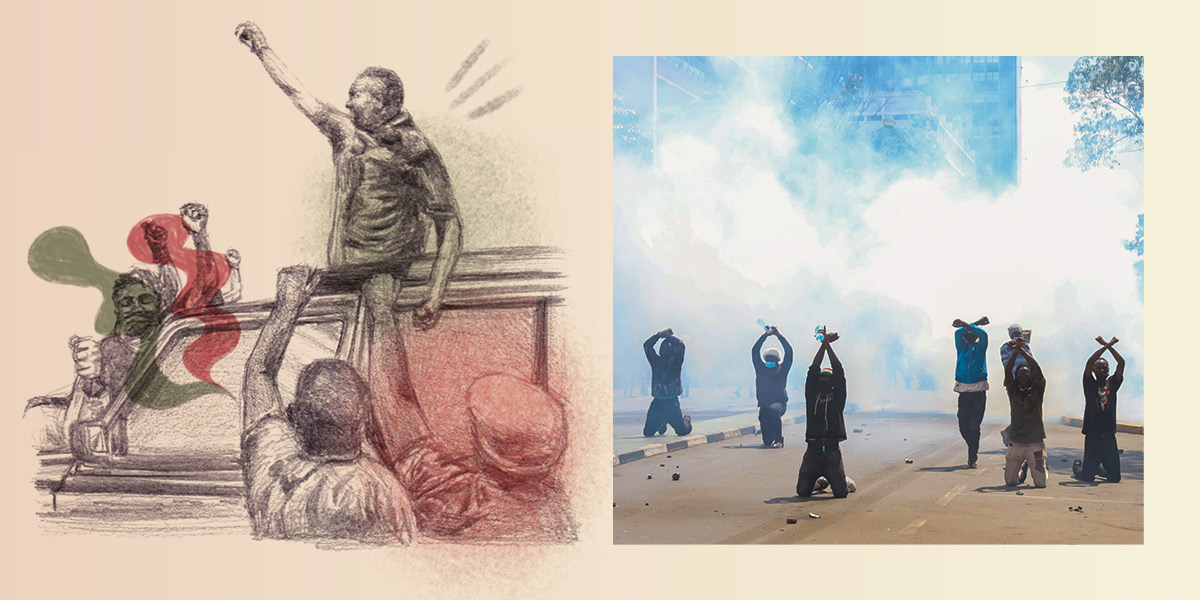

Gen Z protests

Kebaso’s campaign was prompted by June’s youth-led demonstrations, dubbed the Gen Z protests. Thousands of young men and women from all walks of life took to the streets in droves to protest against a finance bill that would have introduced punitive taxes at a time when the cost of living was already unbearably high. Armed with smartphones and bottles of water (in case of tear gas), the youth daringly stormed the parliament building on 25 June. This dramatic invasion generated international and regional media interest. Youth in other African countries, emboldened by the Kenyan example, declared they would be staging their own protests to demand accountability and good governance from their governments.

But the protests came at a heavy price. More than 60 young, unarmed protesters were killed by police officers, some of whom were masked, suggesting that there was a secretive paramilitary force operating in the country. This was followed by a spate of mysterious abductions, some of which resulted in murder.

Some of those killed or abducted were student leaders. Morara himself was arrested briefly by unknown armed people and then released. The authorities, including the president, have denied knowledge of these murders and kidnappings of innocent civilians, despite evidence provided by human rights organisations and other groups. Ruto referred to those killed by police as organised criminals who had infiltrated the protests.

Extrajudicial killings by police, especially in low-income urban areas, are hardly a new phenomenon in Kenya. Wanjira Wanjiru, the founder of the Mathare Social Justice Centre, a human rights organisation based in one of Nairobi’s largest slums, says that it is the normalisation of these killings that birthed her organisation. Her brother was one of many in Mathare who were killed by police. ‘It’s like a cleansing of the youth,’ she says. Wanjiru was among those who took to the streets in June. People like her, aged 35 or below, comprise nearly 80 per cent of Kenya’s population. It is a demographic the government cannot afford to ignore.

A generational shift

The protests led President Ruto to agree to not sign the finance bill into law. He also dissolved his entire cabinet, but promptly reinstated some of his former cabinet secretaries, even those that had been implicated in mega corruption scandals. This reignited the movement’s resolve; from fighting high taxes, the focus shifted to governance and wastage and pilferage of public funds.

The youth-led movement has taken not just Kenyans by surprise but the international community as well. For decades, citizens have been programmed to believe that corruption is a way of life in Kenya, and they can do nothing about it. Corruption scandals in past regimes barely elicited a shrug because those found to be most culpable were neither taken to court nor held accountable by the executive.

Despite the state-led terror unleashed on young Kenyans, this youth led movement has resulted in a seismic shift in the way citizens engage with the government

A generational shift is taking place. Most Kenyan politicians came of age during the dictatorial Daniel arap Moi regime of the 1980s and 90s. President Ruto himself was a protege of Moi and once was part of a youth group bankrolled by Moi whose main task was to bribe and silence those opposed to his regime. But a generation whose parents quietly bore the indignity of deteriorating services and bad governance have decided that enough is enough. Perhaps emboldened by social media, this tech-savvy generation has brought to the fore issues that have bedevilled the country but which few challenged because doing so felt pointless – and life threatening.

This youthful demographic has also been quick to realise that Kenyan politicians cannot be trusted – they can easily switch alliances and political parties for their own selfish individual interests, and don’t seem to have any ideology, except amassing as much as wealth as quickly as possible and living large. For example, Raila Odinga, once a respected popular leader of the opposition, is now singing the president’s tune after the president agreed to incorporate some members of his party into his cabinet.

Hope despite terror

Kenyan youth are deeply aware of the fact that the decisions made by the current crop of old-school politicians, many of whom have been accused of corruption and other crimes, will deeply affect their future, and they are determined not to let that happen. New punitive bills introduced in parliament are set to negatively impact small-scale farmers, and a mining bill will likely lead to more pilferage of natural resources. A new much-loathed healthcare system that is already showing signs of crumbling and the possible leasing of Nairobi’s main international airport to a controversial Indian company for 30 years are also some of the issues that this generation is contesting.

No one can quite predict where the movement will lead, given the increasing strong-arm tactics employed by the government and don’t-care attitude of the president. Under Ruto, Kenyans expect to see the authority and independence of the judiciary, the media, anti-corruption watchdogs and other institutions undermined significantly. Kenyans are likely to go back to the bad old days of an imperial presidency.

However, there is hope. Despite the state-led terror unleashed on young Kenyans, this youth led movement has resulted in a seismic shift in the way citizens engage with the government. This spontaneous, organic movement is significant in two important ways. One, it is leaderless; there are no politicians or parties leading the pack. This means the president cannot ‘buy out’ the opposition, as he often has. Two, it is driven largely by social media; the call to protest was mainly via social media platforms, which is unsurprising given that Gen Z is Kenya’s first ‘digitally native’ population. This means the movement cannot be easily controlled by state organs – unless it is countered by shutting down the internet or social media.

What Ruto and his ilk have refused to accept is that the horse has already bolted. The revolution has begun.