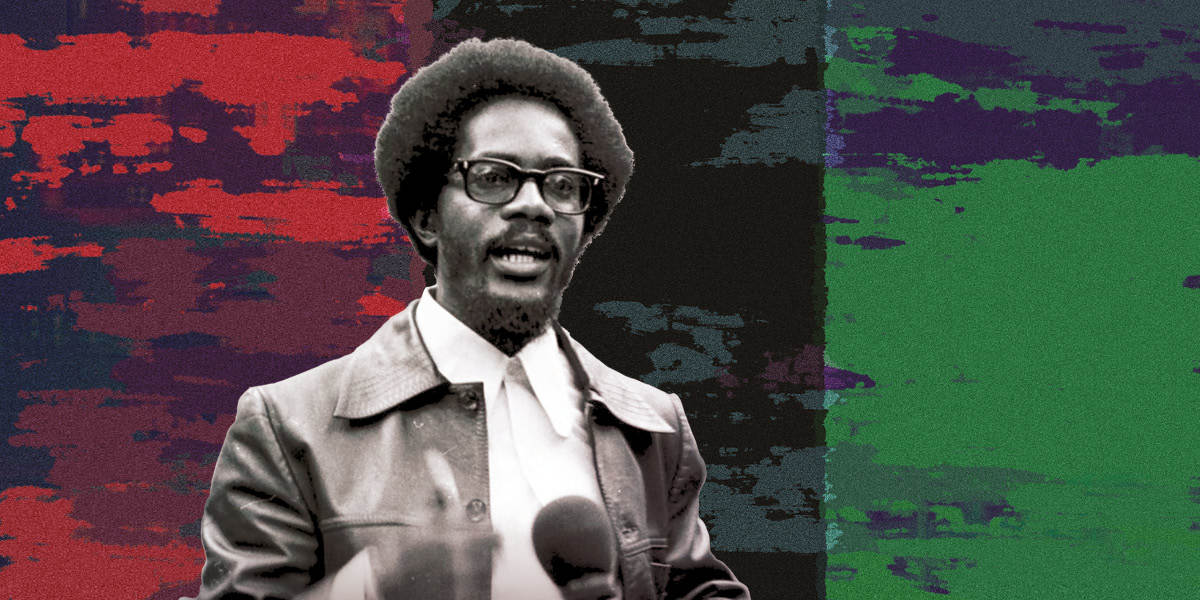

Walter Rodney, a Guyanese Marxist, was a giant intellectual force on black, Marxist, and pan-African thought and action. Today his works, including How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, first published in 1972, are eagerly consumed by young African and black diaspora students, artists, organisers and intellectuals. In our Walter Rodney People’s Public Revolutionary Library, a collective started in 2019 by student activists in Pretoria, South Africa, his works are always on loan.

It’s by reading Rodney that we understand our generation as one that has inherited neo-colonialism. Rodney warned that national liberation struggles in Africa were ushering in neo-colonial states. We see that today. So too, then, do we understand that the fundamentals of the African revolution remain the same today as they did for Rodney: the total liberation of Africa, including an end to white supremacy and African elite domination.

Take South Africa as an example. We hear apartheid ended, but the structures of inequality remain in place. In the current energy crisis – or better, ‘energy racism’ as it’s been called – it’s the poor, usually black, who suffer. People go without electricity for up to 16 hours a day. To blame are the mismanagement and neoliberal policies implemented by the ruling African National Congress.

The fundamentals of the African revolution are the total liberation of Africa, including an end to white supremacy and African elite domination

There’s also the striking hypocrisy of the governments in the global north. Europe industrialised through coal mining, but Africa is told to ‘collectively’ accept responsibility for the planet’s unparalleled levels of carbon emissions. In 2021 the German government promised the South African government €700 million to decommission coal-fired power plants in order to transition to renewable energy. But Germany quickly replenished its coal supplies after the Ukraine war started.

This tragi-comic situation proves Rodney right. European imperialism and resource extraction, not any inherent social or biological traits of Africans, are central to the continent’s poverty and underdevelopment – past and present. Political independence, although crucial, hasn’t meant true emancipation.

Examples of struggle

Rodney and his wife Patricia are examples of how to practice solidarity and organising. Alongside their three children, the Rodneys dedicated their lives to the struggles of ordinary people. In 1974, when Walter Rodney returned to his native Guyana after a period of teaching and organising in Tanzania (he had also been in London and Jamaica before that), he was meant to take up a post as a lecturer at the University of Guyana. But he was blocked by the Guyanese government.

Rodney was offered several appointments in universities in Europe but declined them. Instead, in Guyana, he joined the newly established Working People’s Alliance, and would emerge as a leading figure in the growing resistance against the increasingly authoritarian People’s National Congress Reform (PNC) government.

In the years of struggle before independence, national liberation movements masked the contradiction between the petty bourgeoisie, whose main interest was replacing Europeans within the state apparatus, and the masses, whose main interest was radical social transformation. But decolonisation did not result in an improvement in the material conditions of most people. As Amílcar Cabral, the revolutionary anticolonialist from Guinea Bissau who fought the Portuguese, bemoaned, Africa transitioned from colonialism to a ready-set trap of neo-colonialism. This was enabled by African elites, who Rodney said ‘dance in Abidjan, Accra, and Kinshasa when music is played in Paris, London, and New York’.

Rodney was killed by a bomb in his car in Georgetown, the capital of Guyana, in 1980. In 2022, the Guyanese government accepted responsibility for his murder under the then leadership of Forbes Burham, who was in power from 1964 to 1985.

It’s a familiar story. Pio Gama Pinta (1965, Kenya), Larbi Ben M’Hidi (1957, Algeria), Ruben Um Nyobé and Félix-Roland Moumié (1958 and 1960 respectively, Cameroon), Patrice Lumumba (1961, DRC), Eduardo Mondlane (1969, Mozambique), Amílcar Cabral (1973, Guinea Bissau), Thomas Sankara (Burkina Faso, 1987) – all were staunch anti-colonialists who were executed or assassinated.

Renewed commitment

Today, even if they are clearly dissatisfied, people are profoundly depoliticised. We need to reclaim the meaning and practice of Pan-Africanism, and renew our commitments to liberation and to the sacrifices made by Rodney and others. In recent years, there has been a resurgence of social movements across the continent that are working within local communities and forging connections across borders in Africa and the black diaspora, in which we, the youth, have a key role.

In South Africa, students have led the way in political organisation against white supremacy and colonial ghosts. The reverberations of the Rhodes Must Fall and Fees Must Fall campaign, which emerged from the University of Cape Town, are still being felt across the globe. These protests, the largest post-apartheid higher education uprisings, demonstrated that the Marikana massacre – when South African police shot and killed 37 striking miners – was not an anomaly in the so-called ‘rainbow nation’ but rather an intrinsic feature of this neocolonial state.

We need to reclaim the meaning and practice of Pan-Africanism, and renew our commitments to liberation and to the sacrifices made by Rodney and others

In Azania, our Walter Rodney People’s Public Revolutionary Library, is a small but crucial space, allowing activists and organisers to access books, pamphlets, journals and spaces to think in the spirit of Rodney.

Meanwhile, in Kenya, over 70 social justice centres in informal settlements are proving increasingly essential in political education and organisation against the onslaught of neoliberal policies and neocolonialism. In Tanzania, movements such as the Tanzania Socialist Forum (Tasofo), popularly known in Kiswahili as Jukwaa la Wajamaa Tanzania (Julawata) are deeply entrenched in working people’s struggles and resistance.

Across these spaces, as we think of Pan-Africanism today, it is often Rodney who we are discovering for the first time, returning to for guidance and building on. We see the potential of Rodney in all of us. His life and legacy continue to be remembered among activists with various community-based organisations and activists in diverse places. It is for the future he dreamed of for all of us that we continue our fight, and through this struggle, Rodney lives on.