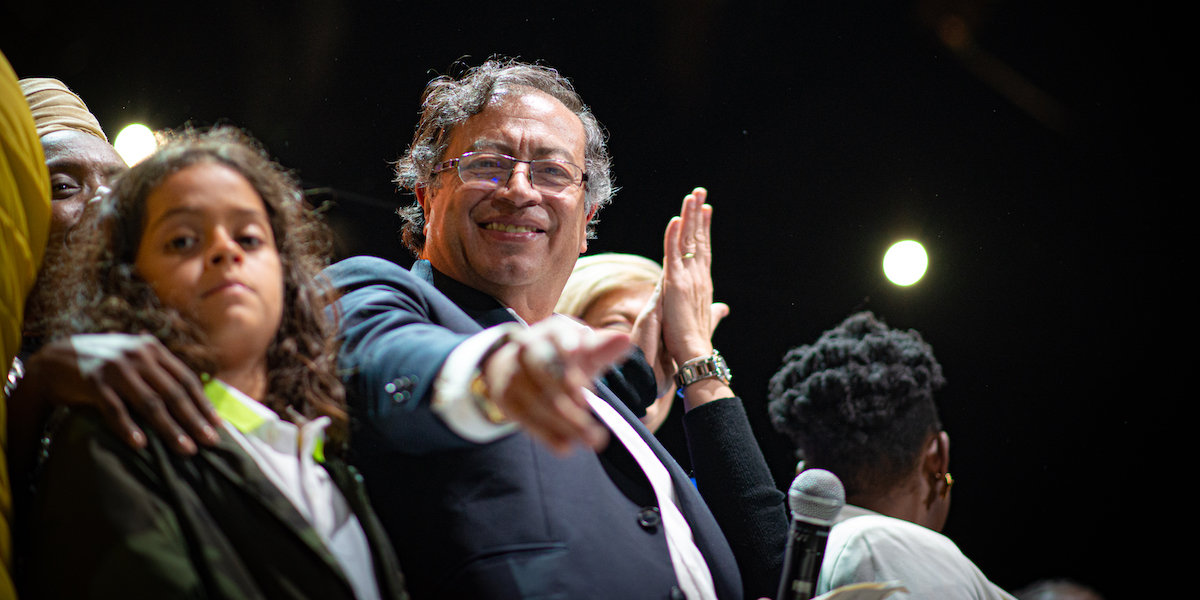

The government of Gustavo Petro and his vice president, Francia Márquez, began with a bang. The duo was sworn in on 6 August, 2022 amid a diverse crowd of guests from Afro-Colombian, indigenous, and rural populations that had long been alienated from parliamentary politics. The streets outside of the inauguration were more reminiscent of an open-air party with expectations among those present sky-high.

A mere eight weeks later, however, many of Petro’s most ambitious plans have been walked back or delayed as he confronts the reality of governing in Colombia. In addition to challenges from those who oppose his political agenda, Petro has also found himself dealing with infighting in his cabinet and political party, all of which is occurring against the backdrop of a conflict that has worsened considerably in recent years.

Peace as a flagship commitment

Since his first day in the presidency Petro insisted on a policy he describes as ‘Total Peace’, a series of measures that propose direct negotiation with various armed actors in the country, such as leftist rebels the National Liberation Army (ELN) and the largest narco-paramilitary group in Colombia, the Gaitanista Self Defense Forces (AGC), or as the government calls them the ‘Clan del Golfo’. The proposal is extremely popular among Petro’s supporters, but some experts have serious doubts about whether negotiations with every armed group in Colombia are truly possible.

The government initiated peace talks with ELN in the past, but negotiations were abandoned by then-president Iván Duque after the rebel group bombed a police academy in Bogotá in 2019, killing 21 people. Petro has formally re-invited exiled ELN leadership in Cuba to talks, suspended the arrest warrants that forced them into exile after previous negotiations were abandoned, and re-instated the legal protocols that allow them to formally sit down as part of official negotiations with the government.

The president has also chosen to promote ‘humane security’, a concept that intends to transform the military doctrine of the ‘internal enemy’ that has governed the conduct of the country’s armed forces for years. As a step toward this ideal, the government has forbidden the air force from conducting bombings on rebel camps where children are present.

In the last four years, at least 29 minors were killed in air attacks committed by Colombian public forces, despite the fact that social organizations have warned that this constituted a clear violation of international humanitarian law.

As part of these efforts to change military culture, Petro has looked to new leadership across the institution. He has also prioritised promoting soldiers who have training in human rights and without connection to human rights violation scandals.

In the same legislative package, which now awaits approval from Congress, Petro proposed a civilian service alternative to compulsory military service for Colombian males, as well as a legal apparatus to fund these programs.

Miguel Suarez, of the Foundation of Ideas for Peace (FIP), believes that ‘Total Peace’ cannot be implemented without tackling the underlying material conditions in the areas where peace is lacking.

‘I see the foundations that underlie “Total Peace” with great optimism,’ he said, ‘but one must not fall into that enthusiasm without first realizing that there are some critical challenges that remain and that a concrete plan has yet to be established.’

Inheriting economic and social crisis

According to several economists in the country and complaints from Petro himself, after the presidency of Duque, Colombia was left with one of the highest deficits in its history, totalling 6.8 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).

Taking this gap into account, the already ambitious plans of the new government become even more complex. This is coupled with the creation of new ministries, such as the Ministry of Equality and the Ministry of Security and Coexistence, which both require their own budget.

To increase revenue, Petro and his new Finance Minister, José Antonio Ocampo, have proposed a tax reform bill that would increase collection by about 1.8 per cent of the GDP —a risky decision in a country that saw a national strike last year, a result of a fiscal reform initiative cutting public services, mushroom into massive nationwide protests.

Unlike the tax reform of 2021, Petro initiative raises taxes on companies in the financial sector, extractive industries, unhealthy foods, and upper-class private citizens – measures he claims will raise more than six billion dollars without impacting middle and lower classes.

The government has proposed tax reform to increase revenue — a risky decision in a country that saw national strikes last year

The new Ministry of Equality (once approved by Congress) will be headed by vice president Márquez, who in the presidential campaign was a strong proponent of women’s rights. This is not a minor issue, since young people and women were a key driving force behind the victory of Petro and Márquez.

For Victoria Ramírez of the Peace and Reconciliation Foundation (PARES), the new Ministry would ‘represent giving importance to a structural problem in Colombia: inequality between men and women. It is essential and urgent for the state to build public policies that eliminate discrimination and ensure the prevention and eradication of any violence against women.

Francia Márquez, a black and openly feminist vice president, is widely expected to play a central role in the fight for the rights of the historically excluded, such as women and the LGBTQI+ population.

Ultimately Petro faces the immense pressure of fulfilling a host of promises to his diverse coalition of supporters: dismantling the infamous riot police ESMAD, which in the last national strike committed serious human rights violations, stronger commitments to women’s rights, and land redistribution, an issue that has been the backbone of the conflict in the country.

In regards to land reform specifically, Petro faces growing tension with indigenous movements in the department of Cauca who are in an open battle with multinational companies for lands they claim were stolen.

In his first speech as president-elect on September 14, Petro called on society to contribute to the long-awaited peace-building efforts: ‘Transforming Colombia into a country of “Total Peace” is not an exclusive task of the government… or of the people who are armed. “Total Peace” is a task for all citizens.’

Whether or not this is true, it is Petro who will be judged by his success in charting a new course for Colombia.