Following the murder of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish woman, by the Iranian state’s ‘morality police’, the Council for Organising Oil Contract Workers’ Protests (COOCWP) published a statement of condemnation. A week later, the workers issued another statement to the Iranian authorities, asking, ‘How long will our streets be dominated by the violence against women, under the pretext of hijab? How long will our lives be dominated by financial insecurity and hunger?’

By comparing the oppression that women have faced at the hands of the state to their own insecurity as pawns in a capitalist economic order, the COOCWP statements highlight a growing collective revolutionary desire within Iran. The wave of voices, images and footage coming from the protests in Iran have shown that these transformative desires are being made concrete on state infrastructure through gestures of sabotage.

Slogans such as ‘Zan, Zendegi, Azadi’ (‘Woman, Life, Freedom’) written across walls and mountains; the hacking of the Iranian state’s national television by the Anonymous collective; the turning red of pools and fountains in Tehran by an unnamed artist; displays of female rage in the public sphere; and oil contract workers’ blocking of roads with stones – these are all important gestures because far from heralding ‘the end of politics’, they instead relocate it outside the realm of governmental institutions, onto the streets.

Oil workers’ historical struggle

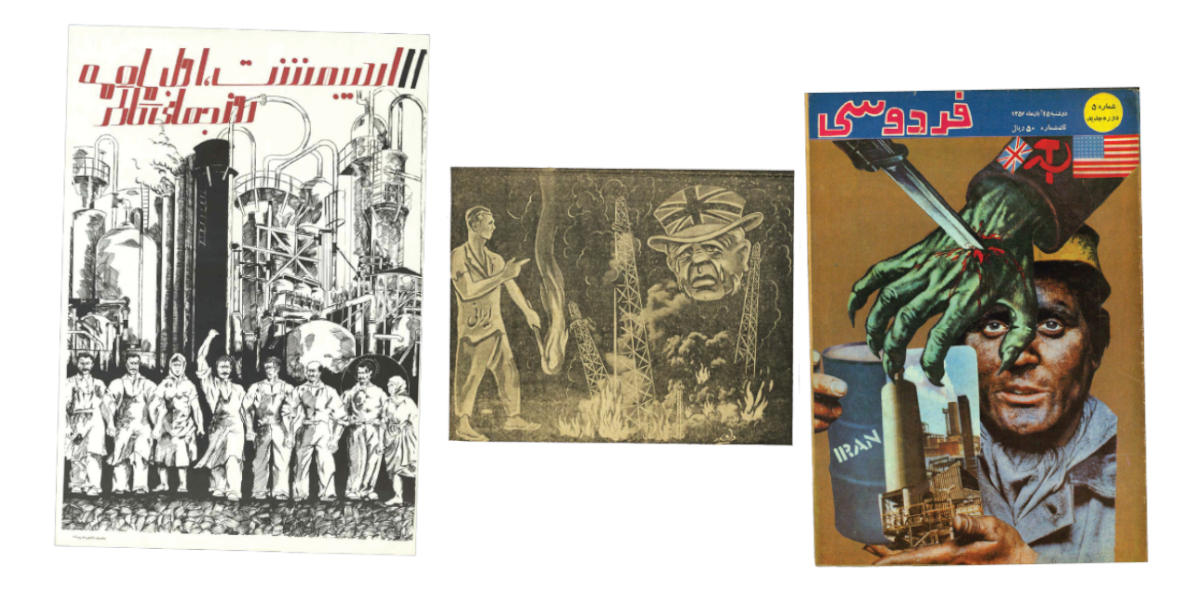

Historical examples of strikes in the Iranian oil industry were evoked when COOCWP workers in Asalouye stood in front of the refinery and storage terminal, spreading stones on the surface of the road while chanting against dictatorial oppression. In May 1951, when the radically pro-Mosaddegh [the Iranian prime minister overthrown in a western-backed coup] newspaper Shuresh published an image of a determined oil worker protesting against the colonial ownership of Iranian oil. The solitary, defiant figure, who had nothing but a fire-torch to fight with, became the face of national resistance. Similar imagery was carried once more on the cover of Ferdowsi magazine in October 1978, which again depicted the struggle between the solitary, male oil worker against colonial and state power.

When comparing the images of current strikes to historical depictions of oil workers in popular media it becomes apparent that whereas the images of 1951 and 1978 showed the workers in proximity to core oil infrastructure, the modern-day actions reveal a distance: the workers are not directly sabotaging the flow of oil but disrupting the roads leading to the refinery. The contract oil workers have to use stones on the access roads to interfere with the efficiency of labour by proxy, due to their inability to shut down the refinery directly. This is the concrete manifestation of the Islamic Republic’s increased surveillance of the workforce, which is contingent upon dividing it.

The separation of employed, unemployed and under-employed workers can be traced back to the racialisation and segregation of the workforce in the colonial era. Today, the objective remains largely the same: preventing strikes. The state’s control of the type and number of workers who are allowed close to the core refinery is one of the ways the oil industry infrastructure prevents workers from effective sabotage of production. This is the logic the global oil industry has been modelled on. The desire to end such state practices was expressed in the COOCWP statement, which urged the permanent workforce to join the contract workers’ strikes.

Indeed, the blocking of roads is a gesture that relocates politics out of the simplistic power paradigm of ‘the worker’ against ‘the state and colonial power’, pointing at the complexities of the labour composition in contemporary Iran and the intersection of global capitalism and the Islamic Republic.

The division of labour

In the past, oil workers have worked against the odds to generate political change by sabotaging production. In the current strikes, the fact that the actions were initiated by contract workers is crucial in understanding the contemporary significance of workers’ political mobilisation. The historian Peyman Jafari explains that there is a noteworthy distinction between the contract workers – mainly active in the oil industry’s construction – and permanent workers, who, at the time of writing, have expressed their solidarity with the protesters but have not joined the strikes.

The permanent workforce’s reluctance to engage in direct anti-state action is partially due to the division of labour and the violent oppression contract workers have been met with. This is not only in the context of current uprisings, but also past protests against the state’s labour policies. Moreover, as permanent workers are pushed further into the insecure realm of contract work by the state, they are more reluctant to join the strikes.

The icon of the oil worker as a solitary man standing up to power has been replaced by figures aligned with the resisting women now symbols of revolution

Even though strikes and gestures of sabotage organised by oil contract workers might not be as effective as historical oil workers’ strikes, these blockades are still important for several reasons.

First, they function as a critique of the division of labour that dictate which segments of the working class count as political actors and which do not. The opposition of oil workers to state/colonialism is a historical binary that is not only visible in the images described above but also dominates the Iranian revolutionary imaginary. This binary does not allow for nuance between the different kinds of oil workers, thus overshadowing the reality of contract workers under increased processes of neoliberalisation and state oppression.

Second, the direct action on the streets positions contract workers within the broader context of the anti-state revolution. As Jeff Diamanti and Mark Simpson argue in their essay ‘Five theses on sabotage in the shadow of fossil capital’ (Radical Philosophy, June 2018), sabotage of various forms goes against capitalist desires by creating counter-dispositions. In Iran today, this is created through ‘radical situations of resistance’ that each function as rods tying together the growing revolutionary web. This consists of various gestures of sabotage by workers and protesters that transform their performers into agents of potential socio-political change rather than the subjects of a state.

Revolutionary counter-dispositions

‘L’, the anonymous writer of ‘Women reflected in their own history’ (first published in English in the Arab ezine Jadaliyya on 5 October) describes a string of gestures of sabotage she witnessed on the streets, in which the disruption to urban infrastructure plays a central role in the creation of revolutionary counter-dispositions. The web of ‘situations’ created by protesting women is not restricted to the street, just as counter-dispositions are not restricted to the realm of energy politics.

It is a web that includes all protesters, as well as oil workers and many other segments of Iranian society. The historical icon of the oil worker as a solitary man standing up to power has been replaced by faceless figures aligning themselves with the resisting women who have become the symbols of the revolution.

The sabotage of roads is the creation of a ‘situation’ that gestures towards a revolutionary counter-disposition that is rapidly expanding – one that uses the streets as its concrete embodiment and is a reaction against the totality of the Iranian state, which depends on processes of neoliberalisation to oppress the workforce.

The prominent characteristic of this revolutionary counter-disposition is that it neither seeks the circulation of capital, nor does it sustain state ideology by contributing to the smooth functioning of its infrastructure. Its political modality aims to abolish the Islamic Republic through interference with its infrastructure, resulting in the rupture of capital.

It is not dependent on the masculine articulations of counter-politics, but requires, and creates, unexpected ‘new openings’ that can function as spaces to forge solidarity. This makes the continuation of anti-state protests possible and allows for the critique of the entanglements of the Islamic Republic and global capitalism.