Shahd Abusalama has been made a refugee more than once. Even before she was born, she was made a refugee.

‘The home is amazing, it’s an abstract home, it’s a home that we never managed to hold or see close,’ she says of her first, imaginary, home – the one which was taken from her family decades before her birth in 1991. ‘When we were kids, if you ask any refugee child where they’re from, they will tell you the names of the dispossessed villages that may not even exist today that our grandparents have fled from in 1948. So I come from Bayt Jirja and Isdud, two of 531 Palestinian villages and towns that were completely depopulated and destroyed.’

Today, Shahd is an associate lecturer at Sheffield Hallam university, having left the Gaza Strip in 2013 to pursue her education on a scholarship. As a result of the Israeli government’s blockade of Gaza and the inhumane policies of the British Home Office, she has seen her parents just once, for a short time, since. Her brothers and sisters also reside around Europe, unable to return home.

Some days before I talked to Shahd, her eldest brother Majed had been arrested in Berlin for attempting to commemorate Al Nakba, the catastrophe that consigned the family to refugee status. In September 2021, Shahd, Majed and the rest of the Abusalama family attempted a reunion in Istanbul after their years of enforced separation.

‘My parents, my youngest brother, my niece who’s approaching four years and her mother, they all managed to leave the Gaza Strip to find a secure place where we could all meet. All my siblings made it from their dispersed places of residence while I got stuck in the UK. The last year, I was in the process of applying for a permanent residence and it took a whole year, actually beyond a whole year, because for the last six months of my refugee travel document, which is timed with the expiry of my refugee biometrics card and residency, is basically useless in the last six months. To travel, they require at least six months’ validation. I tried to talk to MPs, no one could help me to get my documents on time. So I ended up in a situation where I was imprisoned in the UK, unable to travel, while my family made it out of the world’s largest open-air prison.’

After three months of waiting for Shahd, her family, resigned to an incomplete reunion, left Istanbul and scattered back to their homes. As Shahd tells it, their contemporary ‘story of dispersal’ began in 2012 when her oldest sister left for Spain. Now, ‘all of us are refugees… And it’s very painful because we never thought that our reality would be like this. When we left, we thought that we’d finish our studies and come back, but actually, the reality was way harder than we ever expected and return to Gaza, you know, with the conditions that it is under – the siege, people get stuck in Egypt for months waiting to enter to Gaza and on the other side as well… it’s a symptom of how Palestinians are criminalised and perceived as a threat and although it’s brutal, although it’s illegal, although it’s in breach of human rights and international conventions, it continues to happen. So all of us have had their own journey with the hostility of Europe and its racist policies. As we sought to establish a safer life for ourselves, we were met by other violent structures.’

Shahd and her siblings on New Year’s Eve 2012

Dabke

Sheffield wasn’t a completely alien place to Shahd when she arrived to complete her PhD. As a 13-year-old, she travelled to the city as part of a tour to perform Dabke, the traditional dance of Palestine and the wider Levant. Then, it took three attempts to get the young dance troupe out of Gaza. They were twice turned back by Israeli officials at the border with Egypt. On the third attempt, they succeeded. This was Shahd’s first trip out of Palestine, out of Gaza, out of her Jabalia refugee camp.

‘I love Sheffield because I am surrounded by amazing people here who became like family to me, family outside of Palestine. And I noticed that there’s something almost stronger than me inside me that pushes me to create these families wherever I go and I guess it’s maybe a survival mechanism. I thought it would be nice, having these memories from my childhood, I thought it would be nice to reconnect with Sheffield. However, it’s difficult, like it’s not a normal reality, I don’t live a normal reality and I’m aware of that and I’m also here as a refugee and I have these struggles that are very unnecessary, just very oppressive really, you feel the oppression under your skin when you encounter official government processes, and all these constant confrontations that I’m not asking for and are thrown at me.’

These ‘confrontations’, including suspension in the first week of Shahd beginning her teaching career at Hallam, twist like the live cable from a taser around her precarious status in Britain and her maltreatment by the Home Office.

I’m living in the middle of contradictions and I’m always struggling in between those structures of power

‘I always feel at risk and I’m aware of these hostile processes and how they try to make us scared of even calling for our basic rights. I know that I’m dealing with a serious risk here and, in the latest campaign against me, they were trying to, in the defamatory articles against me, they were trying to indicate that I am not going to be a good citizen, for example, or to frame me as a terrorist. Every application, every formal government application we are asked to do as refugees and residents, we are always asked to clear ourselves of any terrorist activity or even support for any terrorist activity, but you are met with a system that has a completely different interpretation, or lens, to yours.’

‘When I think of the Home Office, what comes to mind first? It’s the separation of my family, I think of all these restrictions, the foreign policies that this country perpetuates against us, the discrimination, the feeling of limbo. I see it as inherently racist. I don’t think many are aware of the ways this country practices violence against refugees and we’re humiliated every step of the way.’

‘I remember crying my eyes out when I applied for asylum. It was this realisation that this is my only way, my only option, which was ultimately no option because, like, you’re free if you have options but, in my case, I didn’t have options. That was the only way I could be anywhere because the doors to Gaza were closed in my face thanks to the siege.’

‘You feel the hostility inside the Home Office and you feel the hostility whenever you have to present your ID, the ID that the UK gives to asylum seekers and this ID is very stigmatised in British culture and it is, for me, the only form of identification, and I would worry to use it in order not to instigate a racist or upsetting action against me.’

‘And on top of this, to have to report at a centre every week for six months, and those six months could be forever, you never know, because this is the reality, it’s a reality of uncertainty and it’s a limbo, and I was at that time just surviving day-by-day, really, and I saw all these cases of refugees, people who have fled war-stricken countries, poverty-stricken countries, most of them are ex-colonies of Britain and they are humiliated, they are coming here trying to find safety, trying to find a better life and some of them, a mother, I remember, she was 10 years waiting for a residency. So when you have these examples around you, I was so scared, I wasn’t sure what could happen to me, or where I could end up being..’

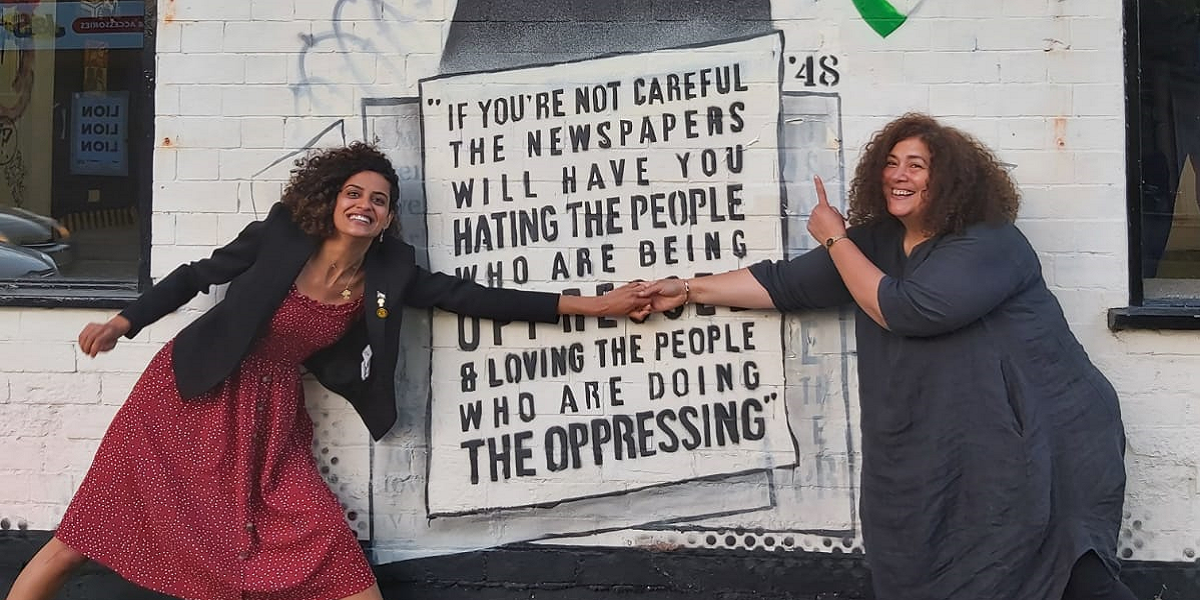

Shahd and her friend Shams holding hands across a mural of Malcom X made by Birmingham-based artist Mohammed Ali during the Israeli attack on Gaza in May 2021

Truth of the Palestinians

So Shahd, for the time being, is in Sheffield and her parents are in Gaza with her youngest brother and her other brothers and sisters are dispersed around Europe and their minds are with each other and with Zayd Mohamed, Saeed Ghoneim and Shireen Abu Akleh and the thousands more victims of Israeli occupation.

‘I live between here and there ever since I left. I mean, to be honest, at least when I lived in Palestine I was completely in Palestine but, when I left, I became restless. It’s a state of restlessness and disintegration that’s haunted me ever since I left. I’m always in so many places at once; most of the time, I’m feeling physically here but my mind is there. And how can I? How can I detach myself while my family’s still there and while I know first-hand what is going on?’

‘I’m living in the middle of contradictions and I’m always struggling in between those structures of power. I feel trapped in violence that extends from Palestine to here and I don’t know how to get free from it. I’m trying my best, but even when I call out what is obvious, when we call out the oppression, we are silenced and so I always feel alienated. I go to banks and then I learn that banks invest in arms companies that aid Israel’s aggression against the Palestinian people. JCB have been called out by the UN for their involvement in Israel’s settler colonial expansion in the Occupied Territories. My university is holding business partnerships with JCB and when we try to raise these issues with the university, we are silenced and we are accused of causing reputational damage to the university.’

When put like this, it becomes clear how integral the system of oppression in Palestine is to the political economy of the Global North. The barriers to any semblance of justice seem mammoth, the processes to be gone through in attempting to extricate European universities alone from complicity exhausting. Yet, whether it’s this fight or the one to see her parents again, Shahd is nothing if not persistent.

‘I really hope to bring them to my graduation in November. They have missed out on so many occasions that happened in my life and I don’t want them to miss out on this too. I feel like, I miss them so much, you know, they didn’t celebrate anything that I achieved and I missed so many things that happened on their end, so I really wish that they could come and be proud for a tiny bit before they go back to the headaches that we cause them all the time. They worry so much about us because they also see how we’re struggling. They thought that when we were out [of Gaza] we would be safer. And they knew, of course, that we would never let it go, we would never forget our roots, we would never forget the injustices that we saw with our own eyes, but they never imagined it would be this intense.’

‘You cannot believe how much hope my case has generated amongst Palestinians. I was getting very moving messages from girls who remain in the refugee camps in Palestine and they saw me coming all the way from a refugee camp and making it here and becoming an associate lecturer and finishing a PhD and still fighting for my people’s rights and they were sending me beautiful messages, saying how I made them believe, how they could see the possibilities and how they’re proud and making themselves feel heard in just telling our story because, at that time, they weren’t trying to just silence me, they were trying to silence the voice, the truth of the Palestinians.’