When it comes to immigration, our politicians are rarely shy about manipulating figures, misrepresenting facts or dog-whistling racists. They deny centuries-long migration to and from Britain and intentionally obscure that ‘border control’ is a very recent invention. Concurrently, they claim Britain has a ‘proud history’ of ‘welcoming migrants’ – so claimed Priti Patel, who as home secretary introduced legislation that would have barred her own parents from the UK.

Politicians do this to create scapegoats, who distract from policy failures, and to stoke xenophobic divisions among workers. Understanding the roots and impacts of migration law is an essential tool in the longstanding battle against borders and the violence they inflict.

Inventing the border

The Aliens Act 1905 was the first legislation designed specifically to restrict immigration – and to define some groups as ‘undesirable’. It was prompted by antisemitic associations of rising poverty and overcrowding in east end London with the arrival of Jews fleeing persecution in the Russian empire – termed in 1898 by the Board of Trade as ‘immigration of the most destitute type’.

Permission to land was assessed subjectively and granted verbally by the UK’s first immigration officers, if a migrant could prove sufficient financial means, that they had not previously been expelled, and that they were not a ‘lunatic’ ‘idiot’, infirm, or criminal. The exception for ‘crimes’ of a religious or political nature introduced the concept of asylum to UK law.

National insecurity

Passed on the eve of war, the Aliens Restriction Act 1914 required migrants to prove their identity and allowed internment and deportation of ‘enemy aliens’. The Aliens Act 1919 extended those laws into peacetime, mandating that all over-16s register with the police, and removed exemptions for refugees. It gave the home secretary powers to order any deportation they deemed ‘conducive to the public good’.

Introduced amid chronic unemployment, the act first made explicit that labour-market dynamics motivated immigration policy. It mandated that aliens obtain permission to work, limited their employment rights and, prompted by Russian revolution anxieties, curtailed their ability to promote industrial action.

Selective asylum

Thousands of refugees fleeing Nazi Germany and Franco’s Spain arrived during the 1930s, as newspapers fed antisemitic campaigns against Jewish émigrés. In the absence of asylum law, they were granted or denied entry on the basis of general assessments including self-sufficiency and good health.

War again transformed the law. As a signatory to the United Nations’ 1951 Refugee Convention and 1967 Protocol, Britain committed protection first to European war refugees, later to ‘all persons fleeing conflict and persecution’. Initially administered through resettlement programmes, from the 1970s individual asylum claims became more common. Demonisation of refugees as ‘queue jumping’ and ‘invading’ were already commonplace, then focusing on Asians fleeing east Africa.

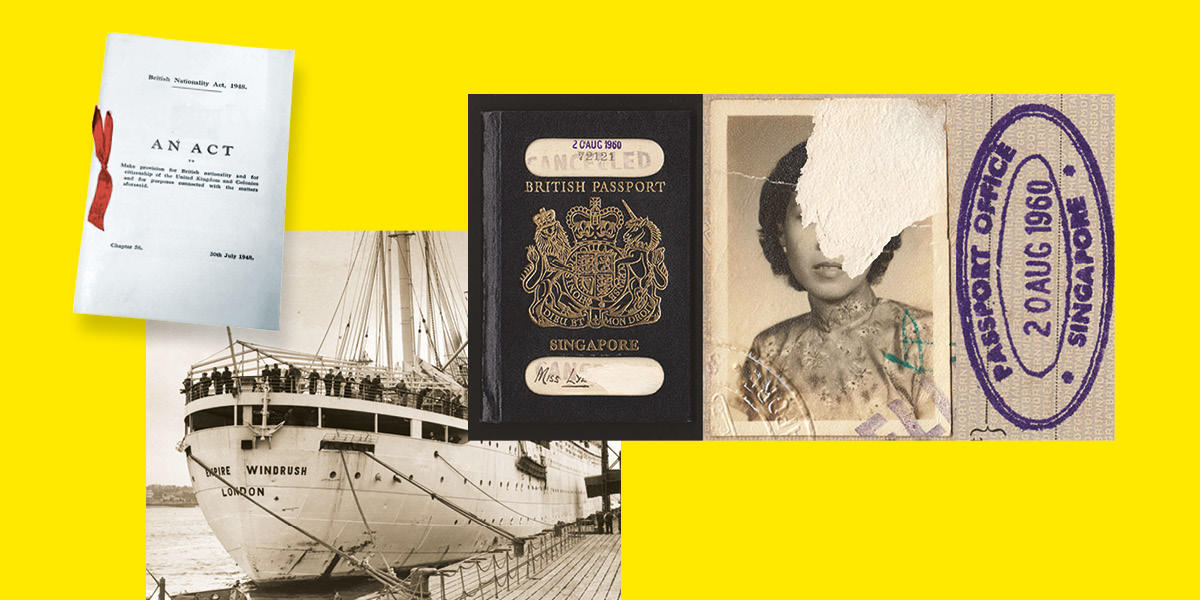

Subjects of empire

Concepts of citizenship evolved radically after the second world war. The British Nationality Act 1948 granted all British subjects across the empire a right to abode in the UK and allowed English-speaking aliens ‘of good character’ to become naturalised citizens. Part reward for wartime service, part solution to labour shortages, it heralded mass migration to Britain, characterised by the passenger ship Empire Windrush.

Overtly racist backlash prompted rollbacks. The Commonwealth Immigrants Acts of 1962 and 1968 introduced new migration limits, ancestry rules for citizenship and work permit requirements – prompting Labour MP Charles Royle to accuse MPs of ‘voting for a colour bar’. The 1968 act first sanctioned deportation outside wartime.

A new ‘common wealth’

The Immigration Act 1971, introduced further immigration and employment restrictions for Commonwealth citizens, criminalised anyone breaking the new rules and shifted the onus onto individuals to prove their status – a root cause of the 2017 Windrush scandal. It came into force on 1 January 1973 – the same day that Britain joined the European Economic Community (later absorbed into the EU), granting reciprocal freedom of movement to worker citizens of other (predominantly white) member states. Anti-immigrant sentiment remained largely focused on non-Europeans – until Britain opened labour markets to citizens from new central and eastern Europe EU states, in 2004.

Fortress Britain

The British Nationality Act 1981 abolished ‘citizenship of the UK and colonies’ and created ‘British citizenship’, limited almost exclusively to those born in the UK to at least one citizen or settled parent (including, for the first time, the mother).

With citizenship redefined and post-cold war dynamics opening up new travel routes and conflict zones – including sites of western military intervention – British attention turned to the rising numbers of refugees. The Asylum Acts of 1993, 1996, 1999, 2002 and 2004 installed increasingly punitive processing, adjudication and ‘management’ procedures – including retractions of welfare supports and expansion of a privately-run detention estate.

From hostility to violence

The 2010-15 coalition government’s ‘hostile environment’ for illegal immigrants codified xenophobia. Immigration Acts of 2014 and 2016 mandated widespread ID checks – turning employers, landlords and healthcare providers into immigration officials. This led to unlawful deportations, including among the ‘Windrush generation’.

The Brexit referendum emboldened post-2016 governments to tighten visa restrictions, curtailing legal routes for migrants. The Nationality and Borders Act 2021 and related ‘Rwanda plan’, superseded by the Illegal Migration Act 2023, all break international law recognising refugees’ right to choose and enter a country irregularly, and protecting against deportation to a country where they face ‘threat to their life or freedom’. Each act lays the groundwork for embedding racism even deeper into law.