It is fifty years since the Abortion Act was passed. It is one hundred and ninety years since the last witch was executed in England. Officially speaking.

The Abortion Act, passed on October 27th 1967 was truly transformative moment in the lives of many women, who could for the first time have sex unencumbered by the terror of having to choose between an illegal abortion and an unwanted child. But it’s hard to totally jubilate when the government is propped up by that frothing cabal of anti-abortion reactionaries known as the DUP. It’s hard to totally jubilate when Jacob Rees-Mogg, the next favourite for Conservative party leader has declared his total opposition to the practise — even in cases of rape.

Over the other side of the pond, Planned Parenthood is facing federal cuts that could see it lose 40% of its operating budget overnight. Neither administration is known for their unity amongst the querulous rank-and-file — but this craven parade of suits tends to agree that, in these troubled times of economic paralysis and rocketing inequality, the first order of business is to roll back on hard-won gains in reproductive rights. In all honesty, I’m terrified.

When I mention this to a friend, he is incredulous. ‘But they won’t actually make abortions illegal, will they?’ My only reply is ‘well, why not?’ Posturing on abortions conjures unity among the ranks of reaction in a time of ceaseless back-biting and faction fighting. For the rest of us, it provides a quick dial-in distraction for reliably woeful economic outlook. Such an easy tool for them, bargained for the low low price of the lives of millions of women.

I get it. The incredulity is understandable; anyone in the UK mainland of childbearing age has grown up in a world where abortion access is a given. Veiled in shame, a continual political football — but always there. You might have to troop through a group of god-botherers praying for your immortal soul and that of the ‘unborn child you’re murdering’, but the services are ultimately there. There’s an overwhelming power to the manta that — all this is normal. Then again, normality is a moveable feast.

Grinning ghoulishly from the high windows of power, figures like Jacob Rees-Mogg, Donald Trump and even Arlene Foster can easily seem like relics from a long-dead past. Museum exhibits. We stare at them in fascinated horror, from behind the thick glass of progress protecting us from their teeth and claws. This is 2017, we tell one another. The dead cannot hurt you. But really, we are the curiosity. Modern history is the history of syringes full of soap water injected into uteruses, tactical tumbles down the stairs, botched backstreet surgeries, live babies abandoned, or families with an impossible number of unfed stomachs. When measured against this long sweep of violence, fifty years is nothing. The blink of an eye.

Abortion is still not a right: you can’t demand one simply on the basis that you don’t want a child. Instead, you have to persuade two doctors that the prospect of an unwanted child would drive you mad, or else cause you physical harm. This double-handed medical check is more than the law requires for open heart surgery, or indeed for carrying a pregnancy to term — both of which carry far greater risks than your average abortion. Despite this patrician hangover from the days of full criminalisation, we cannot underestimate 1967 reform transformed lives.

People were granted unprecedented control over their own bodies, unprecedented power to steer the course of their own futures. But not all women in the UK were so lucky. Ireland is one of only two nations (the other being Chile) in which foetuses are protected not just by the law, but by the constitution — putting the kibosh on any standard move towards legalisation. Over in the United States, where abortion is technically legal, pro-life legislators and private insurers have constructed a maze of financial, practical and technocratic barriers to abortion so unnavigable as to make its technical legality of little practical value. To serve a country of 300 million people, there are less than 600 clinics where a pregnant person can obtain an abortion.

Such settlements provide the backdrop to a grim procession of cartoonish cruelty visited upon pregnant people. Recall Savita Halappanavar, who died in 2012 from complications from a septic miscarriage. Her repeated requests for an abortion had all been denied because doctors determined that there was still a foetal heartbeat. Recall that some US states require those seeking abortion to undergo a trans-vaginal ultrasound — an invasive and medically unnecessary process repeatedly called “state-sponsored rape”.

This begs the question of how — even cloistered in the strange golden sociopathy of extreme privilege — legislators could allow this to happen to people. A brief scan of the history of anti-abortion legislation makes the answer clear: it’s not really happening to people. Women are not really people. Such legislation is a playbook of social and legal trickery used to make women’s personhood disappear.

That life begins at conception was never a settled fact even among the most determined of fundamentalist christian pearl-clutchers. In the Middle Ages, the soul was considered to enter the body when the foetus ‘quickened’; started moving and kicking. But wherever you draw the line, debates that take the personhood of foetuses as their central shibboleth end up treating their hosts like human-shaped incubators. Their personhood is not what matters; only whether and how their vital functions can be used to support a foetus. No wonder then, that we dispose so easily of the bodies of women; they are compliant fleshy automata who can be decommissioned as and when their purpose is fulfilled. This is a familiar story in the history of criminalisation. In 16th- and 17th -century Europe, more women were executed for “infanticide” than for any crime other than witchcraft. And the former was often cited as a sure sign of the latter. The need to ‘protect life’ in the abstract makes the lives of actual, specific women, wholly disposable.

In 1929, The Infant Life (Preservation) Act legalised abortion in certain cases where the mother’s life was endangered. This legislation cleared a little ground for some women to procure lifesaving treatment — including, famously, a 14-year old victim of rape, whose clandestine abortion was declared legal on the grounds that “the probable consequence of the continuance of the pregnancy [would be] to make the woman a physical or mental wreck”. But it’s hard to cast this as a triumph for female autonomy, given that women must declare their own mental vulnerability before being allowed an abortion.

A woman’s physical existence could be protected, but only by affirming her mental and legal incompetence. Moreover, the Act also created the offense of ‘child destruction’, which specifically criminalised “any wilful act [that] causes a child to die before it has an existence independent of its mother” — a crime punishable with “penal servitude for life.”

To each generation, its own complex legal and social architecture constructed to dehumanise women. A cursory attempt to trace its foundations finds justifications cobbled together from a mixture of private bigotry, religious conviction, medical concern, political convenience, anxiety about public health and moral decline. None of these sit easily either with one another; or explain why, when the justifications change, the legislation stays pretty much the same. Where a reason is needed for criminalising abortions, a reason will be found.

So instead of asking why abortions are criminalised, perhaps we should ask instead: what purpose does such an architecture of dehumanisation serve? In Caliban and the Witch, Silvia Federici charts the beginning of the modern criminalisation of abortion in an attempt to answer precisely this question. Defining the crime as the the broad rubric of ‘infanticide’, she catalogues state disciplinary methods adopted to break women’s control over reproduction during a moment of economic crisis and demographic shift:

“From the 1580s to the 1630s we see the onset of severe population decline. Markets shrink, trade stops: this is the first international economic crisis. The new leaders of mercantile capitalism agree that the number of citizens determine a nation’s wealth. A fanatical desire to replenish the population –- expressed by writers like Jean Bodin — is reflected in new policies. Infanticide becomes a capital offense. Pregnancies must be registered with the authorities. Marriage is encouraged, and illegitimacy is criminalized. […] Midwives are enlisted as spies for the authorities, and doctors begin to replace them in the birthing room, as they are suspected of infanticide.”

Capitalism controlling women

A moment of intense paranoia. Understandable, perhaps, given that the society’s survival depended — as it still does — upon women performing the hard graft of babymaking, child-rearing and all the domestic labour that comes packaged along with it. In this task, they were failing. Something had to be done.

According to Federici, this history of violence was creative as well as destructive: The erasure of women’s agency and personhood meant that they could be freely treated as productive units, whose bodies and lives must be dedicated to domestic work and social reproduction. Such bodies don’t need to house properly people. Indeed, it’s a little troublesome if they are; those people might have other ideas about how they might like to spend their time. The woman’s unproductive body was the primary site of resistance to capitalism and, as such, needed to be disciplined in order for capitalism to flourish. To be made productive — to put them to work in gestative labour — women had to first be unmade as people. As Federici puts it, “The human body and not the steam engine, and not even the clock, was the first machine developed by capitalism,”

In Caliban and the Witch, Federici explores how witch trials established a patriarchal order by punishing women’s intrusion into the public space as healers, sages, artisans and minor landowners. Those who home-brewed abortion medicines were decried as irredeemably in cahoots with the devil. ‘Witches’ were specifically condemned for their role in defying the godly duty to procreate: the Papal Witch-Bull of 1484 denounced them for “hindering men from performing the sexual act and women from conceiving” and having “slain infants yet in the mother’s womb”.

Disciplining women in this way established women as domestic, gestative and reproductive labourers to replenish the populace of productive workers. In this sense, the Early Modern war on women was an act of ‘primitive accumulation’ comparable to land enclosure: both providing the raw materials for this new mode of production, allowing capitalism to spring from the ashes of feudalism. Set against this historical analysis, two things become clear. Firstly, that social reproduction is vital economic work. Secondly, that anti-abortion legislation is a programme of systematic conscription, enlisting women’s bodies to this cause.

Debates rage on as to whether criminalising abortion actually results in more babies. Economist Steven Pinker has controversially linked falling crime rates to a legalisation of abortions; unwanted children most likely to turn to crime were simply not born. The inverse of this implies. On the other hand, The Lancet recently published a study suggesting that criminalising abortion simply drives the practise underground, herding people into the hands of unsafe and sometimes unscrupulous backstreet abortion providers. In either case, criminalising aboriton gives pregnant people the legal status of meat or machinery, putting their needs second to the needs of production. It performs a neat triage of women into a) those accepting their role as procreator, carer, mother, or b) those who can summarily be burned.

A flamboyant irony, that people who organise under the flag of being ‘pro-life’ can show such scorn for the lives of actual women. Then again, the sanctimony has only ever provided the thinnest of veils for a contempt for the lives of women, and the lives of women of colour in particular. As Angela Davies points out, in Racism, Birth Control and Reproductive Rights, legislation that banned abortions in the US often laid easily alongside forced sterilisations of poor women and women of colour. Where in age of Atlantic slavery, black women were programmatically raped in order to produce more slaves, reconstruction-era whites were struck with paranoia about being ‘replaced’ or ‘overrun’ by the people they could so recently brutalise unchallenged.

Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed in 1906 that ‘race purity must be maintained’ – “blatantly equating the falling birth rate among native-born whites with the impending threat of ‘race suicide’” The result was an whitelash against the possibility of black life. From 1909–1979, state-run programmes sterilised around 20,000 people. Not only black people, but anyone ‘undesirable’: immigrants, unmarried mothers, the disabled, the mentally ill. Practises like it continue through the present day. Though Israel is sometimes praised for its relatively liberal legislation on abortion, that enlightened attitude to female choice didn’t prevent it administering birth control to unwitting Ethiopian women.

Clearly, reproductive control is not simply about encouraging production — but about stamping out the ability for ‘undesirable’ people to reproduce themselves. In the crux of enormous population change and economic crisis, lawmakers redouble efforts to consolidate their control of the means of reproduction; crafting their ideal population from the unbidden mass of human life.

Stop me if this sounds familiar. Coupled with supreme economic stagnation, we’re seeing an ageing population, a fever-pitch stoking fears of ‘white replacement’. Alt-right mouthpieces like Richard Spencer are scaremongering about ‘white genocide’. “Nearly one in three births are to foreign-born mothers as rate hits record high”, ran a recent Telegraph headline. On the right, migrant women and women of colour are on the hook for their dreadful fecundity — and in more liberal zones, its celebrated as the fore that could deliver us from demographic slump, providing a fresh army of young workers. They are both sides of a creepy, intrusive debate that casts peoples wombs as tools to be used for the overall health of the economy. The only question at stake is whose bodies are used, and how. Little thought is given to the idea of providing services to help them in this apparently critical task of world-building. Let alone to the thought that they should be paid for the innumerable hours of domestic labour this implies. Employers, as a rule, only begrudgingly coughs up enough wages for workers to survive — and even that is subsidised by public programmes to . One can only imagine how they would gape and flounder flounder if asked to stump up the cost of the labour making those workers in the first place.

Feminists down the years have dragged some support from the hands of business and government; in the form of child support, pre-school care, healthcare, paid maternity leave. But under the tight-lipped supervision of austerity tsars, even those basic services have been cut to the bone. Naturally — people will still have kids, and do their best to feed them, and to care for themselves and one another. They will simply have to do silently, unpaid and unaided. Where the welfare state shrinks, women’s labour attempts to paper over the cracks. According to some measures, 86% of the austerity burden falls on women. This It is, we are told, a necessary evil to get the debt down, get our house in order. The health of the economy scraped and toiled for by women. Then again, that’s what we are supposed to be for. Disciplined bodies. Productive machines.

So, what reproductive work once briefly was shouldered by public institutions is now being re-privatised, shut off from view, cloistered in the secrecy of homes. The invisible hands at the gears of society are not those Adam Smith predicted. Perhaps this is how demagogues and reactionaries can so easily shrug off the prospects of defunding reproductive services and criminalising abortion. All that work happens behind closed doors.

All that violence in bedrooms and makeshift hospitals. Jacob Rees-Mogg has proudly declared that, despite being father to seven children, he has never changed a nappy. (He was not drawn on whether the same is true for his wife, who is presumably wealthy enough to outsource the more exerting parts of femininity to an army of nannies and cleaners). Strange, perhaps, that women are historically the ones condemned as witches when the worlds inhabited by men like Mogg are utterly mystical. Ruled by laws of infinite motion and spontaneous generation. Children spring up from nowhere, grow untended, learn unbidden. Food cooks itself, dirty laundry disappears, and reappears only once white again.

The production of life is, in the true sense of the world, occult. And women — whether or not they can give birth — seem reliably associated with this mysterious process. One can only wonder what he imagines happens closed doors. I would be suspicious, too, of the power to make life spring apparently from nowhere. I too might start building pyres.

Any one knows that a witch doesn’t go easily to her grave. Federici underscores the ‘double-nature’ of social reproduction: that birthing and labouring and caring produces workers — but it also produces resisters, rioters and radicals. Those undesirable populations some legislators have tried to stamp out before they are born. Women across the world are organising to demand reproductive freedom, childcare and wages for housework. In base economic terms, this cashes out to — the ability to choose their work, and the right to be . In Poland and Ireland, this organising has taken the form of mass women’s strikes. It seems exhausting, numbing even, to have to re-fight the battles won by previous generations.

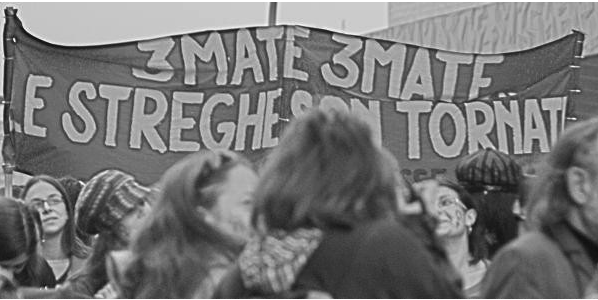

But these previous generations also serve as an example that victory is indeed possible. In 1970s Italy, autonomist feminists took to the streets with banners declaring “Tremate, tremate, le streghe son tornate”: tremble, tremble, the witches have returned.