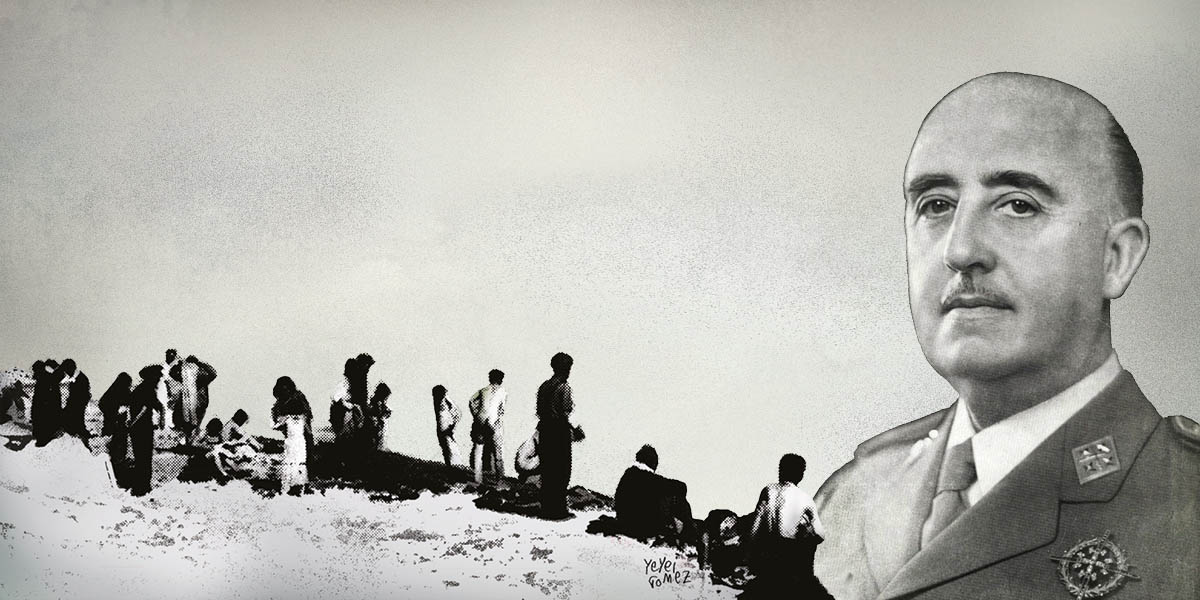

O n 20 November 1975, almost 40 years after the coup d’état that enabled him to become a dictator, Francisco Franco took his last breath in the peace and comfort of his own Madrid home. He had chosen Juan Carlos I, the father of the current king of Spain, to be his successor. In the face of massive social unrest, Juan Carlos was made to choose democracy over the continuation of Franco’s regime. Francoism, however, never really died with the dictator.

Franco’s legacy is still very much seen and felt in Spain, especially with the rise of the far-right party Vox. The problem, however, goes back further than the foundation of Vox in 2013. While one can argue that the process of denazification in post-second world war Germany was not as successful as it may have seemed, Spain never even attempted a similar process after the dictator’s death. Franco was buried in the biggest display of Francoist architecture ever built, the Valle de los Caídos (Valley of the Fallen).

Built between 1940 and 1958 mainly by Republican political prisoners, it is now the resting place of 18,000 Republican victims of the Spanish civil war, most of them unidentified. Franco enjoyed a place in this mausoleum until 2019, when he was exhumed by Pedro Sanchez’s government, and re-buried in his family’s crypt in a cemetery in Madrid.

Amnesty and amnesia

The first democratic elections were held almost two years after the dictator’s death, and Alianza Popular, a political party founded by the ex-ministers of Franco, was allowed to run. This Alianza Popular would later become Partido Popular (PP), the biggest opposition party in Spain to this day. Exactly four months after Spain’s first elections in over 40 years, Juan Carlos I signed the Amnesty Law of 1977.

The law stated that amnesty was to be given to the people who were in prison for committing ‘all acts of political intention, whatever their result, classified as crimes and misdemeanours’ carried out prior to 15 December 1976. This meant that everybody who had been jailed during the dictatorship for political ‘crimes’ (such as being a member of the illegal Communist Party) had to be freed.

It wasn’t until September 2023 that a victim of torture under Franco’s regime was allowed to testify in court against his own torturers

However, this also meant that members of the Franco regime who had carried out torture and other illegal acts against political prisoners could not be prosecuted. It meant they still had the same immunity that they had enjoyed during the regime. They had carried out the torture as ‘acts of political intention, whatever their result’, and thus they were included in the Amnesty Law. The victims of torture during the Franco regime could not get justice in their own country, even after democracy was seemingly restored.

It wasn’t until September 2023, 45 years and 11 months after the signing of the Amnesty Law, that a victim of torture during Franco’s regime was allowed to testify in court against his own torturers. Julio Pacheco, who was 19 at the time of his arrest and torture, is the first person ever to do so, at the start of a historic trial, made possible by the Ley de Memoria Democrática (Democratic Memory Law) passed by the Sanchez government in October 2022.

De-Francoising Spain

The new law replaces the 2007 Historical Memory Law passed by the socialist Zapatero administration. Among other things, the 2007 law recognised the victims of the Spanish civil war and created a map of the mass graves still present in Spain. It also stated that the government would aid in the exhumation of the victims buried in those mass graves.

However, it was largely rendered invalid between 2011 and 2015 by Mariano Rajoy’s right-wing PP government. No public money was provided for the exhumation of victims and governmental activities carried out under the law had to be stopped. Only 6,000 bodies from 370 mass graves had been exhumed since the application of the law; more than 2,500 mass graves remained closed, with more than 130,000 victims buried in them.

Sanchez’s government passed the 2022 Democratic Memory Law to replace the incomplete 2007 law. Félix Bolaños, minister of the presidency of Spain, described it as a law centred around the victims and for the victims, to offer them truth, reparations and justice. It also establishes 31 October as a national day to honour and remember the victims of the civil war and dictatorship. It was this law that triggered the exhumation and removal of the remains of Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera (the founder of the Falangist political party) from the Valley of the Fallen and that finally allowed Julio Pacheco to have his case heard in court.

Private organisations and many activists fight for the victims of Francoism daily, but it has been a huge step in Spain to have the government actively involved in the same fight. A state’s resources are almost limitless, and to use some of those resources to combat fascism is what every country with a fascist past such as Spain should aim for. While Spain still has a long way to go to completely de-Francoise the country, legislation such as the Democratic Memory Law helps speed up the process.

Ideally, there will be a time in Spain when every victim will have been given justice. When Franco’s death anniversary will not be remembered by some, including PP politicians. When finding those missing and murdered by the Francoist side will not be seen as ‘re-opening old wounds’. When the police will treat fascist protesters the same way they treat anti-fascists. And, most importantly, when every one of those laying in mass graves will be brought home.