This year, 2021, marks the centenary of the birth of Raymond Williams, an important thinker and writer on the British left. Born in the village of Pandy on the Welsh border, he went on to study at Cambridge, fight in the second world war and produce 29 critical works, as well as novels and drama, which had a deep influence on the development of critical theory and cultural analysis.

Celebrations of Williams’ work have noted his still-relevant insights on a broad range of subjects, including Welsh and Scottish independence, the relationship of socialists to the Labour Party and the need to bring together socialist and environmentalist impulses.

Equally important is Williams’ influence on the left beyond Britain, from New York Jewish radicals in the 1960s to the contemporary Japanese left. Another lesser-known part of his legacy is his connection with Red Pepper.

Socialist Society

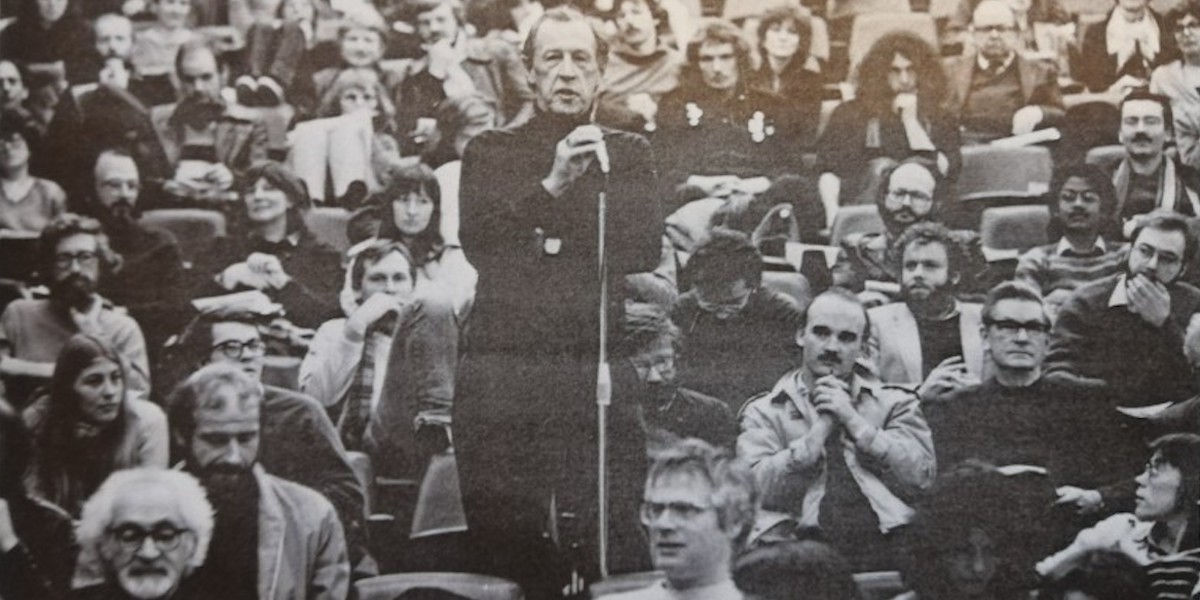

In 1981 a group of British socialists, including Williams, Ralph Miliband and future Red Pepper editor Hilary Wainwright, founded the Socialist Society, which aimed to bring together independent-minded radical socialists, whether inside or outside the Labour Party, and was open to electoral reform and green ideas.

These stances, although controversial on the left at the time, anticipated both the Corbyn project and the red-green alliances now forming in response to deindustrialisation and climate change.

A lesser-known part of Williams’ legacy is his connection with Red Pepper, which launched in 1994

Following the 1984-5 miners’ strike, the Socialist Society worked with Labour’s Campaign Group of left MPs to set up annual Socialist Conferences, whose supporters were convinced that demand existed for a regular independent green-left publication.

After an experiment with a fortnightly paper, and an ambitious fundraising drive, Red Pepper launched as a monthly in 1994. Many of our current supporters date back to that period.

Hilary Wainwright remembers Williams as ‘immensely supportive and always participating as an equal, without condescension or paternalism.’ Wainwright continues, ‘I was shocked by his death in 1988, aged only 66. He seemed still to have so much to contribute. For me The Long Revolution is his most politically relevant book, for today and the future.’

Shifting meanings

Part of Williams’ continuing relevance is his commitment not only to analysing how political discourse shapes how we think about our past, present and future, but also to making this process easy to understand.

This second point was highlighted in our recent readers’ survey, which expressed the ongoing need for breaking down jargon and explaining political terms.

The British left can often seem dominated by academic and media debates that do not prioritise accessibility and inclusion. This limits their potential audience and presents only a partial picture of left-wing thought.

As a working-class boy who became a public intellectual, Williams was conscious of these issues. In 1976 he produced Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. Here he not only considered the meaning of influential terms (including bureaucracy, masses, nature, radical, welfare and socialism), but also tracked how their meanings had shifted historically and the political developments that drove these changes.

Identifying the shifting associations of words, and their use by different groups, can illuminate society and politics – for contemporary equivalents, we can think of terms such as ‘woke’, ‘austerity’ or ‘community’.

Building on this, Red Pepper will be introducing a new regular feature in our next print issue that focuses on similar ‘key words’, both to mark Williams’ ongoing influence on our publication and to ensure the accessibility of political discourse and left-wing ideas.