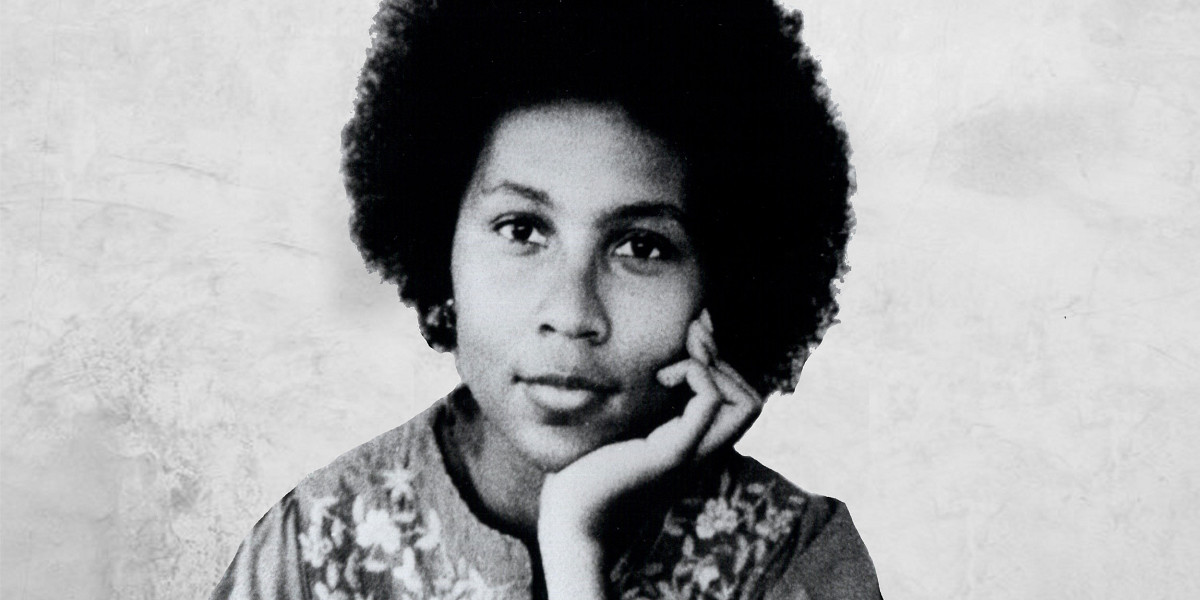

The sudden death of bell hooks on 15 December 2021 created ripples that will be felt for a long time. As a young black working-class woman, bell hooks’s words were initiation into a political trajectory that emphasised the importance of analysing the complexities of human lives through the systems of race, gender and class not as additives but as co-constitutive. What many today seem to credit to scholars like Crenshaw were long the terrain of bell hooks, whose political, pedagogic and critical offerings had an ability to wrap itself around many of us and cradle us through the pain of living under what she articulated as an ‘imperialist, white supremacist, capitalist patriarchy’.

In her death, I have come to wonder how those of us committed to a revolutionary politic mourn the intellectuals who were central to our existence? How do we resist co-optation of their radicalism? How do we continue the projects they start?

As I reflect on my journey with bell hooks, and engage with the various discourses that have emerged since her passing, I learn that there are many versions of bell hooks. There is a diversity in the readings of her work, and there are many interpretations of what her project is and was. Through these reflections, I am also troubled by what has become a cynical celebrification of her work that is often found in the de-contextualised and simplistic quotations of her texts on online platforms. Here her work is repeated and recited like simplistic aphorisms of abstract ‘love’ and ‘self-help’ style quotes instead of the rigorous social and political critique I have come to know as her project.

In the online responses to hooks’s passing, I was reminded of the ways neoliberalism subsumes radicality through commodity fetishism. I think about how this reconstitution of radicality to performance without praxis remains a scourge of revolutionary movements. A practical example of this commodification can be found in many Beyoncé performances; where she adorns herself and her dancers in the uniform of black panthers, fists up in the air, to dance and sing about ‘formation’ on the Superbowl stage. All the while she amasses wealth through a brand that exploits the labour of women in the Global South. I am reminded of bell hooks’s intervention and critique of Beyonce as a cultural terrorist and I wonder how she would feel witnessing similar terrorism be enacted using her words.

Alongside the celebrification of the works of bell hooks is an emergent demonisation of her black feminist project. Many have spoken about the pitfalls in hooks’s social commentary on the Central Park five, comments made about black manhood and her articulations of the violent patriarchal desires of the Black Panther men. Whilst a lot of this critique has been reactionary and can be argued to be bad faith readings of her works, there have been critiques that require some necessary attention. Most notably, the work of Professor Thomas J Curry, who has articulated how these often-problematic caricatures of black men find themselves rearticulated in the black feminist thought of hooks and others. I find it necessary to not simply ignore these critiques but find space to understand and work through some of the contradictions present in the works of hooks and other radical scholars.

The expectation of perfection in any scholarship is a falsehood we come to believe due to the celebrification of radicals. Deifying hooks or engaging the black feminism she offers through a dogmatic lens that assumes infallibility, dehumanises hooks and stifles our ability to engage in what Huey P Newton describes as a revolutionary critique.

‘There are two types of criticism, revolutionary and reactionary. Revolutionary criticism is made on a principled basis, at the proper time … and it is given to reach a higher level of unity and to strengthen the revolutionary camp. Reactionary criticism generally takes the form of a personal attack … It is generally one-sided criticism based on a subjective analysis not having looked at a situation on all sides, and reactionary criticism only served the interest of the fascist and imperialist.’

Rigorous revolutionary critique offers us a necessary radical pedagogy that has become lost in the vampirism of capitalism and limits our ability to mourn radically. Too often, the political lives and works of radicals become abstracted in ‘Goodreads’ style quotes, in cheap sweatshop t-shirts and instagrammable captions. Now more than ever, it is necessary to reclaim our radicals through a commitment to working through and with contradictions, to continue to stretch political scholarship and to engage in an unceasing project of revolution building. I believe this is a radical way to honour bell hooks and so many others who have come before her by recognising their scholarship, humanity and mistakes but committing to working with them still.