In September 2021, an inquest in Halifax heard that a 24-year-old call-centre worker had been suffering from workplace stress and anxiety in the weeks before she took her own life.

According to her GP, she had put in a formal grievance against her team leader and dreaded returning to work after they had had a row. While a handful of newspapers covered the circumstances of her death, it was largely overlooked by the health and safety authorities responsible for ensuring safe workplaces.

There was no inspection of the call-centre where she worked after the suicide. Her death was not officially reported to any public agency. No changes were required to workplace practices or to management behaviour.

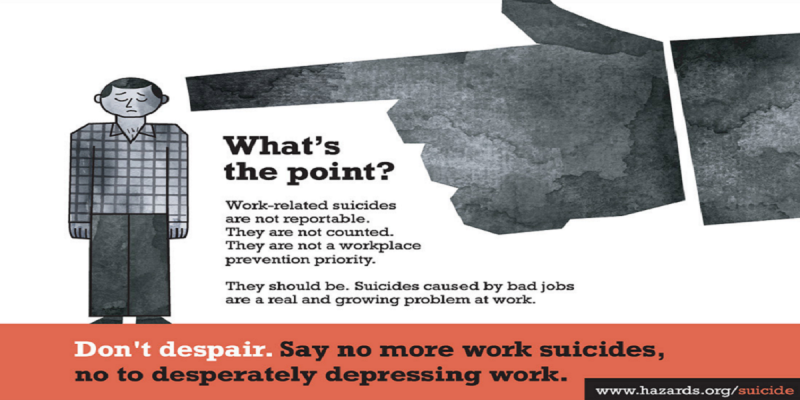

The UK, unlike many other countries (such as France, Japan and the United States), does not monitor, investigate, regulate or legally recognise work-related suicides. Even if it takes place at work or has material evidence of links to work, a suicide is considered a private and individual occurrence.

If you break your arm or get a rash because of unsafe working conditions, your employer is legally obliged to report it to the UK regulator, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), for investigation. A suicide does not need to be reported to anyone other than the coroner.

An invisible phenomenon

Studies show that work-related suicides are on the rise against a background of deteriorating working conditions across the globalised economy. Insecure contracts, longer hours and more intense work, digitisation – all pressure our mental health unprecedentedly.

In the UK, the highest suicide rates are amongst working men aged 40-54. Certain low-skilled occupations have higher suicide rates than others, with construction workers having the highest rates for men and care workers having the highest rates for women. Hazards Campaign estimates that there are 650 work-related suicides in the UK every year and that ten per cent of suicides are work-related. Of course, suicides are the tip of the iceberg in a wider workplace mental health crisis.

According to the government-commissioned Thriving at Work report, more working people suffer from mental health conditions than ever before, and a far higher number than physical health conditions.

Yet, work-related suicide remains a socially invisible phenomenon, absent from government statistics and overlooked by the authorities. In recent years, the HSE has become increasingly active on workplace mental health, recognising stress as is a cause of occupational ill-health and providing a set of stress management standards for employers to follow. However, the HSE is only concerned with workplace stress when an employee is alive. If an employee tragically dies as a result of the effects of extreme stress, this is automatically treated as a private, individual matter with no relevance to work.

Regulatory failures

The World Health Organisation has recently called on countries to improve the accuracy and comprehensiveness of their suicide data. Suicide prevention relies on a timely and rigorous collection of data in order to reveal changing patterns, which population groups are affected and the emerging socio-economic determinants. If you don’t count something, then you can’t account for it and make others accountable. In the UK, the failure to count work-related suicides means that avoidable suicide deaths will continue to take place.

In 2019, four employees working for the same ambulance trust in the south-east of England took their own lives against a background of systemic bullying and sexual harassment within the organisation. The trust had issued 28 non-disclosure agreements in 2018 in response to hundreds of bullying complaints. Ten days prior to the first suicide, a whistle-blower had exposed a toxic working environment at the trust and warned of a heightened suicide risk. Yet, none of the four suicides was subject to an investigation by the UK regulator. None of them was reported to the public authorities as a work-related death. No public lessons were drawn from any of these deaths.

Hazards has been campaigning for legal recognition of work-related suicides since 2003. They recently launched an e-postcard campaign, calling on the HSE’s chief executive to include suicide in the list of work-related fatalities that employers are legally required to report. The HSE has responded to this campaign by claiming that suicide is too complex, subjective and multi-factorial to be considered as a work-related issue. Rory O’Neill, who led the Hazards campaign, told me: ‘The HSE’s problem is not complexity, it is complacency. During site visits, its safety inspectors are required to assess risks present that could lead to multiple fatalities or multiple causes of ill-health and, if so, take appropriate action. HSE guidelines list over 80 conditions […] It is not that the HSE can’t include suicide. It won’t. It is difficult to conceive of a more high consequence event than suicide.’

A sense of injustice

Another harrowing consequence of the failure to report is that bereaved family members are often left with a sense of profound injustice in the aftermath of a suicide. Many feel that the factors which have led to their loved one’s suicide are not taken seriously or investigated properly. The suicide is usually framed by the coroner as stemming from an individual mental health problem, even when there is no previous history of mental ill-health.

Hilda Palmer, from Families against Corporate Killers (FACK), which supports bereaved family members after a work-related suicide, explained: ‘At a time of severe trauma and shock, families are left to cope alone. They are left without being able to explain or find out more about how and why the stress of excessive workloads, and hours, or bullying and harassment drove the person they loved to take their own life. And they are denied accountability by the employers, any financial compensation or sense that lessons will be learned to prevent someone else from dying in the same way. Failure to investigate work-related causes can lead to lifelong, generational stigma, guilt and shame.’

Denying that a social problem exists or claiming that it is too complex doesn’t make that problem go away. Rather, it leads to situations of deep-seated injustice and poses serious risks to health and lives. In 2021, the Workplace Health Expert Committee, an independent expert panel that advises the HSE on new and emerging workplace health issues, discussed a new report on work-related suicide. With growing evidence of the connections between work and suicide, the HSE can no longer justify turning a blind eye.