This is the story of #FuriaTravesti: a collective of people who faced persecution and brutality at the hands of the police, were often thrown from their homes and experienced extreme discrimination. Yet, even while they occupied ‘a non-place’ in the eyes of the state and society, they continued fighting to build new forms of citizenship and rights.

As well as the sweet smell of rose, a name can confer the desire for education, health, work, recognition and the right to live free of violence and stigma. This is a story about the right to self-name.

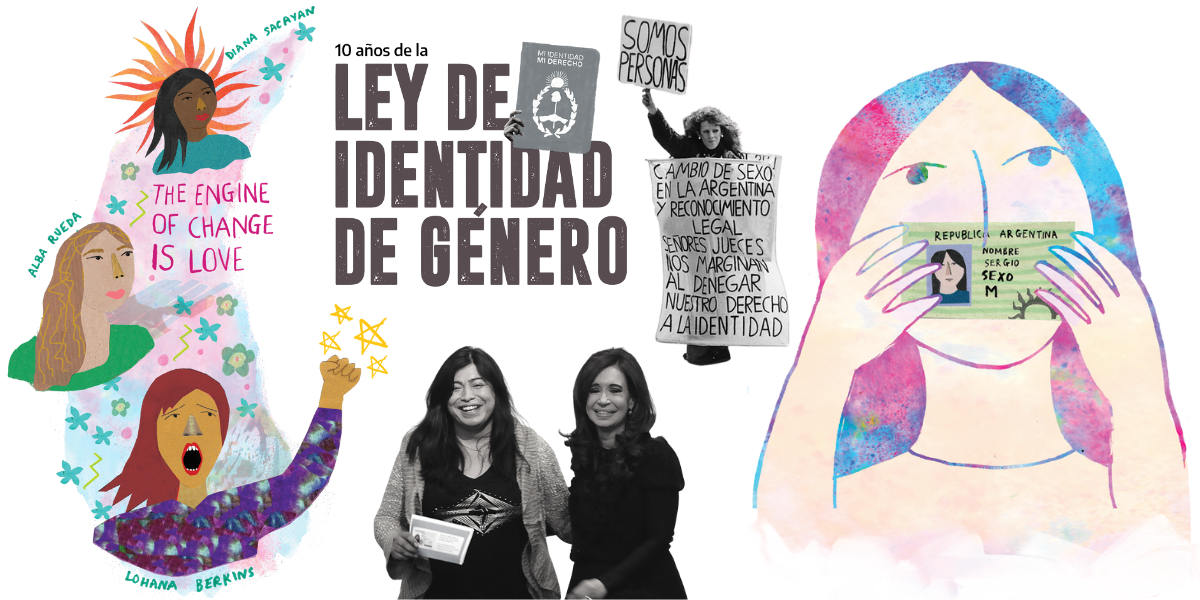

In 2012, Argentina became the first country in the world to allow people to officially change their name and gender without requiring permission from a judge or doctor; without undergoing sex reassignment surgery, hormone therapy or psychological evaluation. Many more ground-breaking policies have followed, including last year’s decree that one per cent of public sector jobs would be reserved for trans people (an umbrella term for people whose gender does not reflect the sex they were assigned at birth).

The law was developed after a 2017 survey found that only nine per cent of trans people were formally employed, while 70 per cent were sex workers. Many do not have access to healthcare. The Argentine struggle for trans rights is far from exhausted, yet it remains a beacon of hope as other countries – including the UK – take regressive steps.

The path towards the 2012 Gender Identity Act carries instructive lessons for parallel struggles, while also being embedded in a specific Argentine context. It was forged by grassroots organisations working via political alliances, collaborating with academics, building popular support and acting both with and against the established legal order.

The Act itself was the tip of the iceberg. Beneath the surface, two key dynamics propelled change: the street as a site of political action and the reclamation of ‘travesti’ as a locus of identity construction and resistance.

From the streets to the legislature

Argentina is a country where democracy is exercised, fought for and embodied through walking and shouting in the streets. Public space, most notably the Plaza de Mayo, has been central to the subjectivity of the Argentine nation since 25 May 1810, when crowds gathered in front of the Cabildo, the nascent government body, demanding transparency and popular participation.

Over 150 years after the May Revolution, in that same plaza, mothers and grandmothers began their walking protest to demand the ‘reappearance, alive’ of daughters and sons ‘disappeared’ by the military junta. Those same grandmothers are still fighting today to identify their grandchildren, stolen as infants by the military in a planned, systematic act of dictatorial oppression.

Shortly after the turn of the new millennium, following years of cronyism and febrile neoliberalisation, the people again took to the streets as multiple and connected institutional and economic crises hit home. As radical thinking spread in the heat of the crises, new and historically marginalised social and political actors grew in visibility, strength and influence.

In that same locus of resistance, grassroots trans rights organisations had already begun to form through shared efforts to repeal colonial-era penal codes that enabled police repression of ‘scandalous’ behaviour, including public cross-dressing.

Multiple groups coalesced into the #FuriaTravesti (travesti fury) movement. These included the Association for the Struggle for Travesti and Transsexual Identity (ALITT) led by Lohana Berkins; the Organization of Travestis and Transsexuals of Argentina (OTTRA, ‘other’ in Spanish) led by Nadia Echazú; the Anti-Discrimination Movement for Liberation (MAL, ‘bad’ in Spanish) founded by Diana Sacayán; as well as FALGBT (Argentine Federation of Lesbian, Gays, Bisexual and Trans), ATTTA (Association of Transvestites, Transsexuals and Transgenders of Argentina), Travestis Unidas (TU) and Comunidad Homosexual Argentina (CHA). The ability to form and sustain coalitions has been central to the movement’s ongoing success.

Early on, the movement appropriated a pejorative term to claim a new political identity, travesti. The term has contested etymology and roots across Latin America. It has a connotation with ‘transvestite’ but also a connection to revue shows, which featured stunning ‘vedette’ stars, combined with the Latin prefix tra-, for ‘across’ or ‘beyond’.

Travesti designates a diversity of experiences and embodiments that do not coincide with traditional state classifications of gender or sex. As a concept and identity, it confronts heteronormativity and authoritarianism – structures that uphold spatial exclusions and legal repressions of people designated as pathological subjects. It is a term used by working-class, rural and Indigenous-descendant people. For Berkins, leader of OTTRA, it connotes a political subjectivity linked to ‘struggle, resistance, dignity and happiness’.

The appropriation of travesti was set against a dominant discourse of dangerous ‘sexual deviation’. This discourse was deeply embedded in Eurocentric legal frameworks and peripheral regulations called ‘edicts’, which punished minor offences such as deceit, carnival, drunkenness, disorder and gambling, as well as ‘transvestism’ and homosexuality.

As a concept and identity, ‘travesti’ confronts heteronormativity and authoritarianism – structures that uphold spatial exclusions and legal repressions of people designated as pathological subjects

The offence of ‘scandal’ and the prevention of ‘dangerous’ behaviour have been used by police as a pretext to stop, detain and investigate people who ‘dressed or disguised in clothes of the opposite sex’ or wore ‘improper clothes’. Notably, these ‘police edicts’ criminalised the person – not their behaviour. Health professionals who tried to assist people in their corporeality also faced sanction for their actions.

The overlapping tactics adopted by the travesti/trans movement – asserting the right to be present and visible in public, reforming insult into collective power and lobbying to repeal oppressive laws – were, in the words of Berkins, designed to ‘demolish the hierarchies that order identities and subjects’.

That struggle is ongoing: although the police edicts were repealed in 1996 following a lengthy and painful battle, the illegality of prostitution and new directives introduced to uphold ‘public tranquillity’ have allowed police harassment and arrests, frequently without a warrant, to continue.

Despite protections won over the past decade, such directives still survive, and are used particularly in provincial districts as a pretext to harass and detain ravesty and trans people. Across Argentina, police brutality remains a common cause of serious injury and death in ravesty and trans communities – and remains a central point of struggle for the movement.

Laws of oppression, laws of resistance

The epic struggle to make the streets safer for travesti and trans people, only briefly narrated above, was both a necessity for survival and an early demonstration of how the law could become a site of resistance, not only a source of oppression. Its generative power, after all, both constitutes and excludes subjects of the state. While the struggle over the public space continued, individual struggles for identity grew alongside.

By the late 1980s, medical and judicial authorities had the power to grant or deny an individual’s request to change their legally recognised sex and/or name following hormonal therapies and surgeries. The first ruling, in 1989, rejected the applicant’s request, asserting the ‘legal truth’ of ‘genetic sex’ – therefore unchangeable via medical intervention. Perspectives began to change following Argentina’s adoption of the core United Nations human rights treaties into the constitution in 1994.

Once the language of human rights entered the judicial realm, the first ruling favourable to an applicant followed – albeit only in 1997, and only on the condition that they underwent feminising genital surgery – which was not available in Argentina – abroad. Soon, however, rulings began to distinguish ‘gender’ from ‘sex’, and named gender as a ‘legal fiction’, not a ‘natural truth’.

By 2003, 17 further rulings had granted name changes and, in some cases, authorised post-surgery changes of registered sex. Judges’ decisions were based on applicants’ ‘naturalness of performance’ and their ‘correct’ embodiment of gender.

The epic struggle to make the streets safer for travesti and trans people was both a necessity for survival and an early demonstration of how the law could become a site of resistance

As knowledge of the rulings spread, self-proclaimed travesti, trans and broader lesbian, gay and bisexual rights organisations (as named above) began to organise collectively to challenge the strict parameters of name and sex recognition laws. They grouped together as the National Front for the Gender Identity Law (FNLID). It lobbied executive powers and parliaments and turned to the Yogyakarta Principles, the international declaration of human rights relating to sexual orientation and gender identity, to support its position.

As a result of FNLID efforts, between 2003 and 2011, the secretaries of education and health of the city and provinces of Buenos Aires and the province of Santa Fe ruled that people could legally change their name based on selfperception – without medical intervention.

In doing so, these provincial- and municipal-level rulings borrowed the Yogyakarta Principles’ concept of gender identity, referring to gender self-identification as a personal right, which ‘corresponds to every person, by their sole condition as such’.

Meanwhile, at the national judicial level, significant parallel battles were being fought – and won. The 2006 supreme court ruling that granted legal status to ALITT reflected an important shift in politics and society. The association, which worked expressly for the rights of travesti and trans people, had previously been denied status on the grounds that its existence did not ‘contribute to the common good’ and that travesti and trans people did not have a legal right to organise and campaign for their rights. ALITT had been undeterred in its fight for recognition.

Another incremental step forward was made through the Hooft ruling in 2008, which authorised an applicant’s change of legal name and sex without requiring genital surgery. Then, in November 2010, the famous Argentine actress Florencia de la V was granted her request to change her legal name and registered sex without having to undergo a ‘sexual adaptation intervention’ (genital surgery). Crucially, the ruling was based solely on the plaintiff’s declaration of will – without use of medical experts or environmental reports.

Florencia de la V was backed and advised by FALGBT, FNLID, ATTA, CHA and others, and the profile of her case indisputably mobilised the public. Following the ruling, FALGBT swiftly began to raise and sponsor further requests, understanding that favourable rulings would enable legislative treatment of a future, appropriate self-identity law.

The same year, the Scheibler case ruling authorised a change of name and registered sex from male to female without medical intervention and using the concept of ‘selfperception’, admitting there were no formal identification possibilities at the state level of the travesti/trans community.

The Scheibler ruling established that gender identity should be legally protected as part of the right to personal autonomy. It also maintained that subjective and bodily experiences that defy the generic binarism ‘do not constitute “deviations”’, striking an important corrective to pathologising legal and medical frameworks.

Widespread impact

Throughout this period, FALGT and other allies in the movement for travesti and trans rights had also been fighting another battle that would have huge legal, social and political ramifications: to reform the civil code to allow same-sex marriage. This struggle also took place in the streets and in the legislature. Mass gatherings, marches and rallies were frequently met by counter-demonstrations.

Progressive figures in different political parties worked together to counter oppositional campaigns mounted by the church and conservative actors, which framed same-sex marriage as an attack on ‘family values’ and harmful to children. The then-Cardinal Bergoglio, archbishop of Buenos Aires (now Pope Francis), called on his faithful to wage ‘a war of God’ against the proposed law, prompting a retort from President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner that he should ‘abandon medieval times and the inquisition’.

Kirchner’s ruling alliance, the Peronist Front for Victory (Frente para la Victoria, FPV), was at the time at the peak of its popularity and held a majority in both parliamentary chambers. It promoted the law as part of its longstanding ‘access to rights’ platform, evoking post-dictatorship commitments to nondiscrimination, social inclusion and fairness in public life.

FALGBT’s strategy was to counter prejudice with positivity. Its chosen slogan, ‘same love, same rights’, emphasised affect and equality, while testimonies from gay- and lesbian-headed ‘diversity families’ were used to counter fearmongering over children, adoption and parenting.

For Argentina, the right to self-identity was entwined with its post-dictatorship commitment to human rights, equality and personal freedom

When put to parliamentary vote, in July 2010, the same-sex marriage bill barely passed, with a deputies vote of 126 to 109 (four abstentions), and a senate vote of 33 to 27 (three abstentions). Following the vote, Kirchner announced: ‘We have not promulgated a law, we have promulgated a social construction’. By the time Florencia de la V’s case hit headlines a few months later, LGBTQ rights discourse was firmly established in the public realm.

A decades-long struggle, propelled by alliances and fought on multiple grounds, had laid the groundwork for the Gender Identity Act to be passed by parliament 18 months later, in May 2012. The law standardised procedures and criteria for people to change their legally registered sex and/or name at the national level.

Notably, the bill received far less media attention than that for same-sex marriage, and passed by a much less polarised vote, including with near-unanimous senate approval. Evidence submitted for legislative analysis had been provided by academics, activists and political advisers, with no public surveys or media debates to influence the vote. The church was quiet on the issue.

For Argentina, the right to self-identity was entwined with its post-dictatorship commitment to human rights, equality and personal freedom. For the world, a decade on, its stance remains a radical proposition.

Legacies, alliances and ongoing struggles

Today in Argentina, anyone over the age of 18 can request rectification of their records at civil registry offices and on their identity document (DNI), the state-issued instrument that unequivocally identifies each citizen. They can do this without judicial authorisation, medical certification or surgical intervention, as the law states that all persons have a right to self-define their gender identity and to live freely according to it, and that their identity must be respected by the authorities.

The wording of the law was sufficiently flexible that the option of an official non-binary sex, ‘X’, could be later introduced, as it was in July 2021 under the Peronist government of Alberto Fernández.

The struggle for travesti and trans rights and freedoms has not slowed down over the past decade, transforming politics and society alongside and as part of broader LGBTQ and feminist movements in Argentina. The paths taken by these movements have not always been linear, and specific goals have received particular emphasis at different times.

It is possible, however, to distinguish how their varied strategies and trajectories have had overlapping and cumulative influence over state discourses, social norms and legal realities. For example, another landmark ruling of 2012 won through tireless feminist struggle was the incorporation of femicide into the criminal code, an important recognition of gender-based and domestic violence.

The same amendment also criminalised hate crimes based on the sexual orientation or gender identity of the victim. Violence against women, however, remains endemic across Argentina, spurring the ‘Ni Una Menos’ (‘not one less’) movement, which continues to demand increased state funding and action in response.

When Diana Sacayan was killed in 2015, the travesti/trans movement demanded that ‘travesticide’ be used in the criminal trial of her murderer. Using the legal framework of femicide, the court included the term in their decision. Discussion over how to make travesticide legally operative remains ongoing.

The deaths of prominent movement leaders Lohana Berkins, Mocha Celis and Nadia Echazu, among countless others, only underscore the urgency of greater action to protect travesti and trans people from violence and improve their access to healthcare and welfare support. All who have died during the fight against invisibility and persecution have left an indelible mark on the survivors who continue their struggle.

Academic and activist Marlene Wayar, Florencia de la V and militant Alba Rueda, the current undersecretary for diversity, are among the many who today carry the torch of public recognition and the right to exist, motivated by Berkins’ final published words: ‘The engine of change is love. The love we were denied is our drive to change the world.’

’The engine of change is love. The love we were denied is our drive to change the world’ – Lohana Berkins

The legalisation of abortion, in 2020, marked another milestone for Argentina. It was won through decades of action, sparked by the National Campaign for Legal, Safe and Free Abortion in 2003 and propelled by multifaceted campaigning, broad-based coalitions and dogged legislative jockeying: draft laws for the ‘voluntary interruption of pregnancy’ were presented and defeated six times in the chamber of deputies between 2007 and the eventual 2020 approval.

Appeals to human rights discourses were also essential to this fight, which worked towards ‘sexual education to decide, contraceptives not to abort, legal abortion not to die’. Cross-party solidarity and lobbying, political manoeuvering by prominent feminist academics and militants, the massive marches of Ni Una Menos, media exposure generated by the Actrices Argentinas collective, among others, and the symbolic capital of the green bandana – echoing the iconic white headscarf worn by Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo – galvanised public pressure into an unstoppable ‘green tide’.

As had been the case for same-sex marriage, the fight to legalise abortion required coalition-building across progressive sectors of the entire political spectrum against powerful conservative actors. The travesti movement consistently supported the campaign for reproductive rights, enthusiastically joining parades, putting organisational names to declarations and always affirming their shared, feminist fight against hetero-patriarchial oppression.

The logic of self-determination and bodily autonomy are, after all, both central to battles for legal abortion and for gender identity – battles that still continue today. The Ministry for Women, Genders and Diversities, also established in 2020, underscores these connections.

In its battle to radically broaden social, political, ideological, personal and legal conceptions of rights, freedoms and justice, the Argentine travesti and trans community continues to achieve wide-reaching impact. Its lesson to the world is clear: if feminism is an emancipatory project to fight oppression, it must include – at the very least – travesti and trans struggles.