If imperialism is what happens when empires expand then colonialism is how they do it. Imperialism comes from the Latin imperium, which means sovereignty or political power. It is what happens when an empire, seeking to enrich itself, extends its reach through brute force into foreign territories for the purpose of extracting resources and labour. Colonialism is when they send settlers to do that work.

Empires have existed throughout history, but none were able to recreate the world in their own image to the extent that Europe has done. European expansion was rapid and dramatic: from 1876 to 1900, colonial powers’ possession of Africa’s landmass rose from 10.8 to 90.4 per cent. By the 1914 onset of war, Europe, its colonies and former colonies had control over most of the world’s population and 85 per cent of its territory.

These colonies came in myriad forms. Some were governed by large corporations, which prefigured the multinationals of today. India, for example, was governed by the East India Company, which acted as an arm of the monarchy; colonial Nigeria came into being under the Royal Niger Company. Other colonies, such as ‘administrative dependencies’, were governed through a system in which colonial administrators worked with native leaders they installed through a system of indirect rule. Others still were governed by settlers, the term ‘settler colonialism’ reflecting the Latin root of colonus, a farmer. Colonial settlers established new societies in a region, either eliminating or displacing its indigenous inhabitants in a quest for resources, land and cheap labour.

The late scholar Patrick Wolfe described settler colonialism as ‘inherently eliminatory but not invariably genocidal’. Demographers are only recently coming to terms with the scale of violence that Spain and Portugal inflicted through their genocidal conquests. Between 1492 and the mid-17th century, for example, the native population of the Americas fell from 50-60 million people to just five or six million, due to a combination of imported diseases and mechanisms used to control and exploit native peoples.

Imperialism and class rule

Imperialists governed territories they had not annexed through informal as well as formal means. Historians John Gallagher and Ronald Robinson famously proposed that ‘informal empire’ was preferred to annexation. Thus, the British empire’s formal governance, at its height, over a quarter of the world’s population was supplemented with the power it wielded over nominally independent countries through local intermediaries and financial domination. ‘Informal empire’ survives into the present – it is what Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana, called ‘neocolonialism’. This requires local intermediaries – a ruling class aligned with the coloniser for its personal gain at the expense of the people.

By the 1930s, West Indian socialists such as C L R James, George Padmore and Amy Ashwood Garvey were spreading the gospel that ordinary people could overthrow empires. In his memoirs, James reflects that most people thought their campaigns for decolonisation after the second world war were crazy. With help from accomplices in the metropole, however, millions of colonised subjects joined trade unions, took up arms and fought for independence.

Imperialism, then and now, was never in the interest of the working class

Meanwhile, Marxists from the colonised countries, like the Trinidadian trade unionist Padmore, made appeals to the Britain working class. ‘The colonial peoples,’ he wrote, ‘are the potential allies of the workers against a common enemy – the British imperialist class.’ For most workers in Britain, the empire was an abstract entity – a minority stood firmly in the anti-imperialist camp; the majority didn’t care. Imperialists, on the other hand, knew very well the link between class and empire.

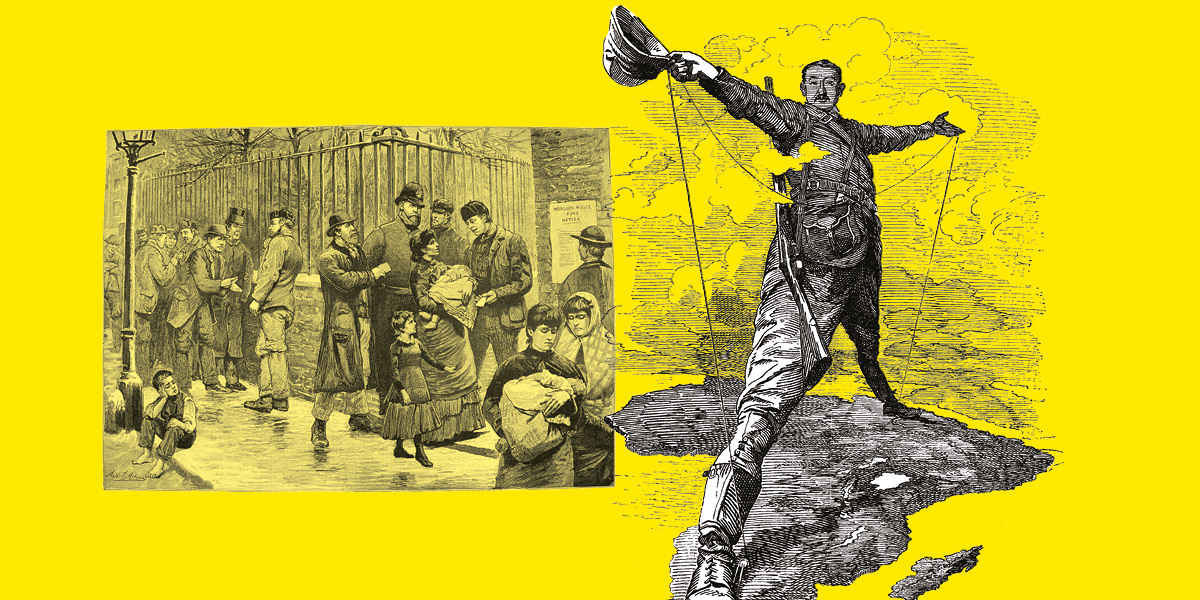

After attending a meeting of unemployed people in London’s east end, where he heard ‘wild speeches’ and ‘cries for bread’, the mining magnate and former Cape Colony prime minister Cecil Rhodes candidly reflected in 1895: ‘My cherished idea is a solution for the social problem, i.e. in order to save the 40 million inhabitants of the United Kingdom from a bloody civil war, we colonial statesmen must acquire new lands to settle the surplus population, to provide new markets for the goods produced in the factories and mines. The empire, as I have always said, is a bread-and-butter question. If you want to avoid civil war, you must become imperialists.’

For Rhodes and other capitalists, colonialism offered a solution to class warfare by creating new markets, occupying the unemployed and preempting demands for bread, socialism and revolution. Imperialism, then and now, was never in the interest of the working class – its ‘benefits’ accrued only to a small ruling class.

After independence

After 1945, most territories held by former colonial powers became independent. This process helped create the illusion that colonialism has come to an end. Through neocolonialism, however, the colonial global order has remained intact. Institutions such as the IMF and World Bank, working in the interests of the capitalist economic system, forced newly independent countries back into submission.

If such means failed, agencies such as the CIA worked to undermine socialist programmes, orchestrating military coups and killing socialist leaders. Figures who pushed for radical visions of decolonisation were assassinated, including presidents Thomas Sankara of Burkina Faso and Patrice Lumumba of Congo. Meanwhile, former colonial powers weaponised foreign aid and incentivised resource extraction at the expense of newly ‘independent’ nations. France, for example, used stationed troop outposts and currency manipulation to control its ex-colonies.

In the 1970s, the co-founder of Guyana’s Working People’s Alliance, Walter Rodney, echoed Franz Fanon in arguing that local careerist, elite intermediaries – the ‘comprador bourgeoisie’ – kept colonialism alive. As the ‘Pandora papers’ (the 2021 exposé of global financial secrecy) reveal, such bourgeoise strata are responsible for helping to syphon $1 trillion out of Africa, through London, to private accounts in tax havens around the world.

Nonetheless, the struggle for decolonisation continues. We see it when Bolivian indigenous peoples fight against the corporate takeover of their territories, or when Palestinians fight for their homes in Sheikh Jarrah. Across the world, people are opposing governments run by elites who hoard their money in the same tax havens as the international ruling class. Protests such as those seen recently in Lebanon, Haiti and Sudan are not only raging against corruption but against neo-colonialism. George Padmore’s insight still rings true: ‘Colonial peoples are the potential allies of the workers against a common enemy.’